I’m watching a man tip his ear into what appears to be a large neon-pink lotus flower. Copper tape delicately loops out of the bloom like some strange stamen as he carefully listens to the tinny sounds rising up out of it.

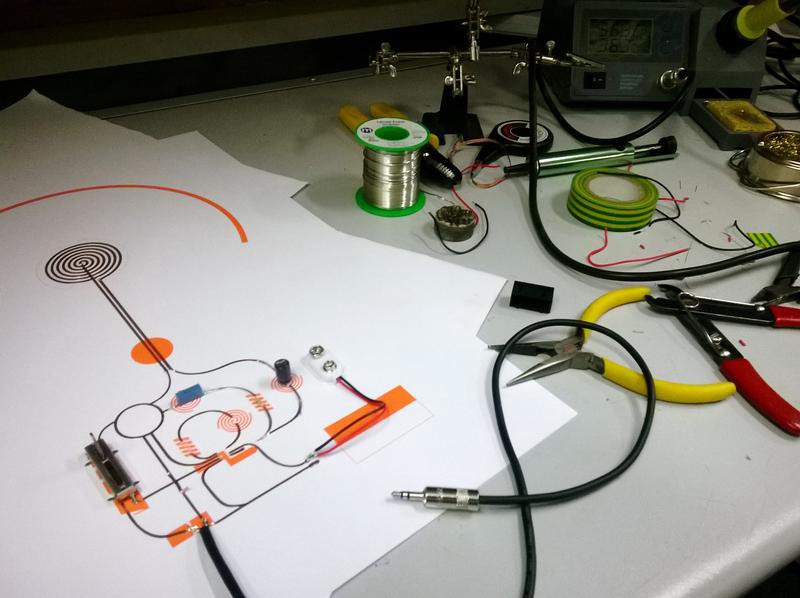

We’re at a workshop on paper electronics run by Coralie Gourguechon, a creative technologist and product designer who has spent the past three years pushing the limits of what paper offers to our understanding of electronics. We’re learning to make low-tech speakers composed only of paper, magnets, and copper wire. The particles in the copper are excited by the magnet, causing it to vibrate–and the movement travels through something thin and light enough to allow for maximum vibration, which is where the paper comes in.

There are good reasons why Gourguechon’s so interested in paper. It’s a hugely versatile substance: lightweight, flexible, biodegradable, renewable, and cheap (even if the environmental impact of its production, at scale, sometimes leaves something to be desired). Stir in the right additives and it can be strong or delicate, opaque or translucent, repel or attract water.

Research around paper electronics dates back to the 1960s, when enthusiasts explored how to use paper in thin-film transistors; currently, engineers are again experimenting with how to use it in transistors, displays, and even solar cells, which could store energy through the paper itself. The development of conductive ink for consumer markets has also led to curious investigations around new forms of circuit. A personal favorite is Tricia Flanagan’s “Blinkifier”: Fake eyelashes coated in this ink form a circuit when the user blinks, lighting up an elaborate headdress.

Gourguechon, however, is more attracted to the craft possibilities that paper permits than in funneling her work toward consumer electronics. “I’m more interested in the exploration of the terrain: The production side of product development is the most interesting part for me,” she explained.

Her passion was piqued three years ago when she built an instruction-kit camera out of cardboard. She became frustrated, however, that the device’s only difference from a regular camera was the material that constructed it. Most intriguing to Gourguechon was the fact that she was creating the camera herself, rather than relying on external production processes. She began thinking about what a camera might look like if the casing were also the instructions for how to build it.

Her focus allies with similar work done by researchers at MIT Media Lab exploring the different types of production between crafts and electronics. Craft education tends to focus on tools and skills, largely leaving it up to the maker to decide what he or she constructs from there. In contrast, electronics education tends to use modular toolkits and building blocks, expecting users to keep to a predecided script. Paper craft circuits can make learning around electronics more appealing and accessible, and challenge cultural expectations around how electronics should behave.

There are previous links between crafts and electronics in industry, though not always successful ones. Professor Lisa Nakamura has looked at how, in the 1960s and 1970s, Fairchild Electronics employed a number of female Navajo workers to build electronic devices and integrated circuits. In its brochures, the company used romantic (and racialized) ideas to justify this decision, describing how the imagination and craftsmanship of Navajo weaving linked to the “personal commitment to perfection” needed for electronics assembly.

By bridging the production and electronic elements, Gourguechon invites us to rethink what these devices actually are, how they behave, and who engages with them. She also helps open the silos between art, craft, and science education. Radio capacitors and speakers were once made of paper before the shift toward metals, resins, and plastic. Looking at the mass of Post-its and copper that surround us at the workshop, she suggested, “It’s not so crazy after all when you think about it.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Design & Innovation section, which looks at new devices, concepts, and inventions that are changing our world. Click the logo to read more.