Right now it’s easy to dunk on Facebook. I’m not saying it’s not necessary to do so–I think this dunking is vital. The short story, in case you’ve managed to tune this whole thing out, is in 2014, researchers were granted really comprehensive access to millions of Facebook users’ profiles (the majority of whom did not consent), and this research wound up in the hands of Cambridge Analytica, a political consulting firm hired by the Trump campaign, which then used that personal data to target and exploit people’s fears, anxieties, and bigotry in the run-up to the 2016 election.

This is all pretty bad! Facebook’s negligence lies at the heart of it–and they’re deservedly getting a lot of heat right now. Yes, they should be hauled in front of every government oversight committee that wants to interrogate them. They should be regulated–I’d prefer substantial measures, but literally anything is better than the total lack of comprehension and/or action our lawmakers have offered up over the past few years. And they should be the subject of the rigorous critique they’re currently receiving throughout the public sphere.

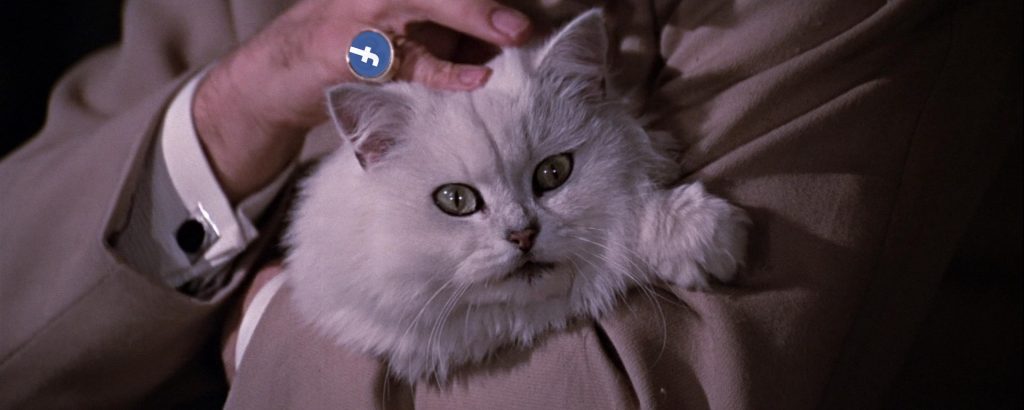

But something struck me, as I was listening to a story about this whole debacle on the radio: “It’s straight out of a spy movie,” a commentator said, referring to secret recordings of Cambridge Analytica’s supervillainish speeches about how they can control people’s minds with data. The commentator wasn’t wrong; when I first heard the recordings my jaw dropped a bit, and since I’d seen a spy movie over the weekend, my mind immediately went there, too.

Cambridge Analytica’s actions are heinous and wildly unethical, but there’s something in that supervillainishness that makes the whole thing a bit more concrete: it’s not the amorphous “Russian meddling” or something as vague as a “data breach” or even that time Facebook themselves got caught A/B testing our emotions and we were all briefly mad and moved on.

We learn careless companies allowed bad actors to obtain our data, but what do they”¦ do with it? You feel unsettled and helpless and you change your passwords and then you forget: most of us linger in this constant state of forgetting about the precariousness of a life online. Cambridge Analytica did something–and can brag to future clients about how they’ll do it again, in precise detail, all while petting a white cat.

With Facebook already at scale–already scaled beyond comprehension, billions of people, close to a third of the world’s population, sharing Tasty videos and racist memes and pictures of their grandchildren–the crisis is at scale, too. It feels enormous, out of our hands and into the hands of governments (don’t get me started on this “nationalize Facebook” meme, unless you can explain to me what that would mean in practice, globally, because then I’m all ears).

But the attitudes on display, the “Who, us? We’re just a tech company/public square/conduit for your conversations” line of deflection is echoed up and down the org charts of Silicon Valley and its counterparts around the globe, from ideas about how “all engagement is a net positive” all the way over to “I’m just an engineer.” Take this this recent incident, when an engineer gave this exact response after developing software that could be abused by the police, and a critic in the audience “quoted a lyric from a song about the wartime rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, in a heavy German accent: “‘Once the rockets are up, who cares where they come down?'”

Software is authored by humans. Digital systems are authored by humans. Humans with different priorities–code, design, reach, engagement, profit, how this all complies with or sidesteps the law–but still humans nonetheless. People, even people who know better, tend to talk about algorithms like they are magic spells, or something that is inherently out of our hands. On an individual level, they’re right, but that distance creates a general sense that they aren’t in someone else’s hands, that they’re just”¦ the way things are. Cambridge Analytica gives us a mustache-twirling villain to focus on, rather than just big systems drifting in and out of failure. But we need to be sure that we keep an eye on the whole spectrum, the engagement-getters and the I’m-just-an-engineer-ers and the assumption that only malicious actors can cause harm.

Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the creator of the World Wide Web, wrote about this yesterday, and despite fundamentally disagreeing with him on the idea that Mark Zuckerberg means well (didn’t you see that movie, buddy?), I love the poetic symmetry of seeing an individual who gave birth to a massive system reminding us that there are humans behind all of this. “This is a serious moment for the web’s future,” he writes. “But I want us to remain hopeful. The problems we see today are bugs in the system. Bugs can cause damage, but bugs are created by people, and can be fixed by people.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Design & Innovation section, which looks at new devices, concepts, and inventions that are changing our world. Click the logo to read more.