It turns out that even rocket science isn’t rocket science anymore. Forget NASA’s multibillion-dollar budget, or even the $74 million for India’s recent Mars observation missions. A new breed of satellites means that anyone can now carry out his or her own exploration of outer space for as little as $35 a day.

“One class of 6th graders ran experiments focusing on watersheds,” said Chris Wake of Spire, a Silicon Valley startup with a fleet of tiny satellites called nanosats. “They wanted to know if they could get a photo of this watershed over time, to see how it’s changing through the seasons.”

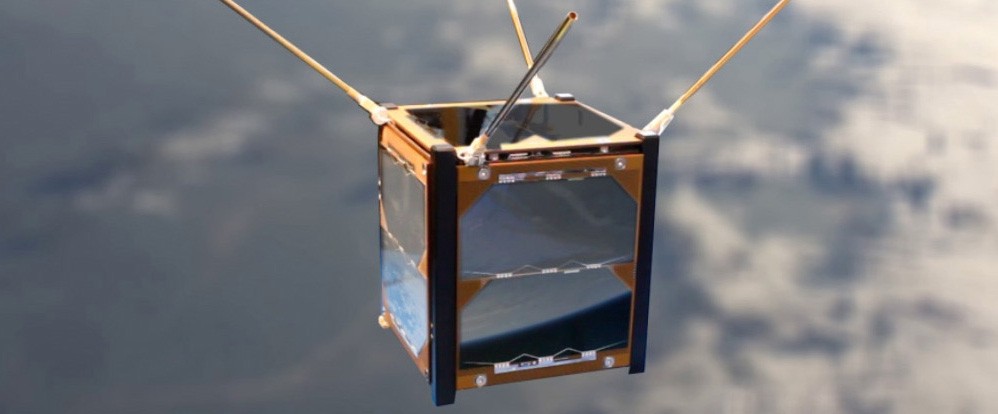

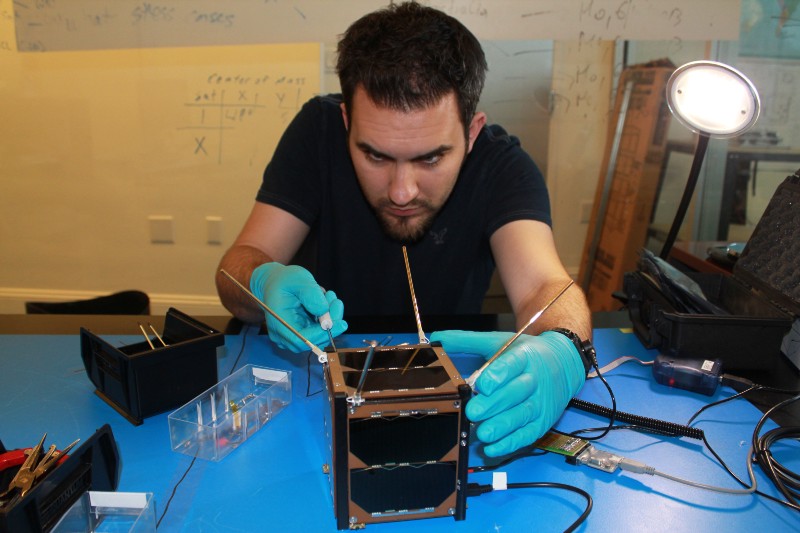

The nanosats, now operated by a spin-off called Ardusat, measure just 10 centimeters on each side but nevertheless manage to carry sensors for temperature, magnetism, luminosity, infrared, and ultraviolet light, as well an accelerator, gyroscope, and a 1.3-megapixel digital camera. None of the instruments are particularly cutting edge, but together they enable citizen scientists and schoolchildren to conduct useful and unique experiments from orbit.

Ardusat helps schools write the software they need to track thunderstorms, measure climate trends, or even gauge the energy consumption of entire cities. It then sells blocks of time on its satellites to run the code, starting from just a few dollars an hour. “There’s a magic moment when students realize that their data is smarter than what’s visualized in a textbook,” said Wake. Users control their satellite from a virtual control center in a web browser, and can also buy cheap Ardusat replicas to tinker with the hardware itself.

That wasn’t possible for the amateurs behind the ISEE-3 Reboot Project, another “spacecraft for all” whose hardware is floating over 3.7 million miles from the Earth. NASA originally launched the International Sun/Earth Explorer 3 in 1978 to study the interaction between the Earth’s magnetic field and solar wind. After completing its mission and being repurposed to study comets, the ISEE-3 was shut down in 1997.

Early in 2014, over 2,000 enthusiasts donated an average of $70 each to a crowd-funded project to bring ISEE-3 back to life to collect more data. Buying, begging, and borrowing the necessary equipment to contact the distant spacecraft, the group succeeded in reviving it and firing its thrusters for the first time since 1987. Sadly, a maneuver to correct its trajectory failed and the team has now lost contact with ISEE-3–this time probably for good.

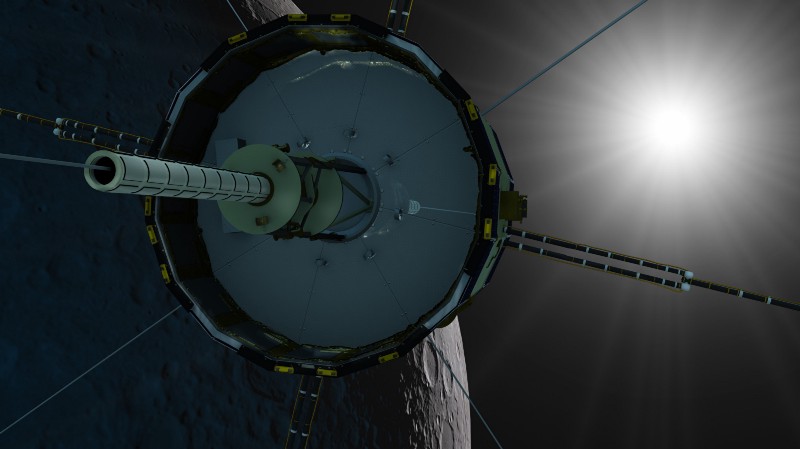

But there are many more crowd-funded projects on the final frontier. The LiftPort Group raised $110,000 to fund research into space elevators–giant, super-strong cables to reach from the Earth’s surface into space–while Planetary Resources raised $1.5 million to build publicly accessible space telescopes that will capture high-resolution images of the Earth or space. The telescopes will eventually be used to map near-earth asteroids packed with precious metals that Planetary Resources hopes one day to access and mine. It successfully deployed its first demonstration spacecraft in July.

“It’s the power of the crowd,” said Peter Diamandis, co-founder of Planetary Resources. “If you’re dependent on innovation from within your company, you’re dead. We’re looking to tap the innovation of billions of people around the world.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Above & Beyond section, which looks at our understanding of the universe beyond Earth. Click the logo to read more.