Chris Albon and the CrisisNET team are on a mission–to democratize crisis data. “For the first time, decision-makers and citizens with limited-to-no experience will be able to use social media-generated data to answer their questions without the need for a costly data science team or expensive analysis software,” he said. Given the amount of data that now exists, making sense of it–and delivering it in a useful form–is a big deal.

Crisis data isn’t new. It’s been available to the disaster response community for years. The problem is that the vast majority of it used to come from official government sources. The rise of the likes of Facebook and Twitter have changed all that.

“Social media has been a boon for data-informed disaster response by providing easy access to near real-time crisis information. The massive value of utilizing this real-time social media data has led to a whole cottage industry of efforts to find insight in that stream of raw, messier social data,” said Albon, director of CrisisNET.

The sheer quantity of this social data presents both a challenge and an opportunity. Making sense of it is where CrisisNET–an Ushahidi initiative out of Kenya–comes in.

Simply put, CrisisNET is a platform for the world’s crisis data, giving journalists, data scientists, developers, and other makers fast, easy access to critical government, business, humanitarian, and crowdsourced information. By reducing the time it takes to access and use crisis data from hours or days to minutes, CrisisNET removes the barriers to big data and empowers communities to create solutions to their own problems.

“When crises hit, timely, relevant data can help governments, local volunteers, and the humanitarian community respond quickly to events on the ground,” added Albon.

Ushahidi should know. Its mapping platform, born out of the Kenyan election crisis in 2008, has since been deployed in all manner of disaster response situations including the 2010 Haiti earthquake. CrisisNET was a logical extension to that groundbreaking work. As its reputation grew, the Ushahidi team found itself increasingly called on to manage the data aspect of crisis response, in addition to discovering and rediscovering good sources of crisis-relevant information each time.

“What we really wanted was a single stream of crisis information, a ticker-tape if you like, which we could tap whenever we needed crisis data, whether we were working on a project on a natural disaster in Asia or political protests in North America,” said Albon.

CrisisNET is that ticker-tape. More specifically, it is a fire hose of crisis data, pulled in from a wide variety of sources and restructured into a single, usable format and made available online. This makes it easy for individuals to find and export crisis data about a given crisis, allowing them to get to work right away.

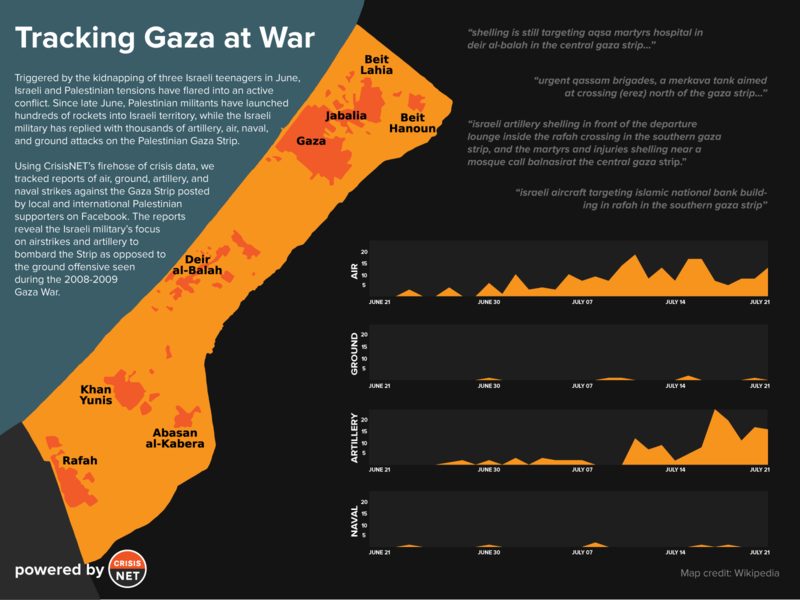

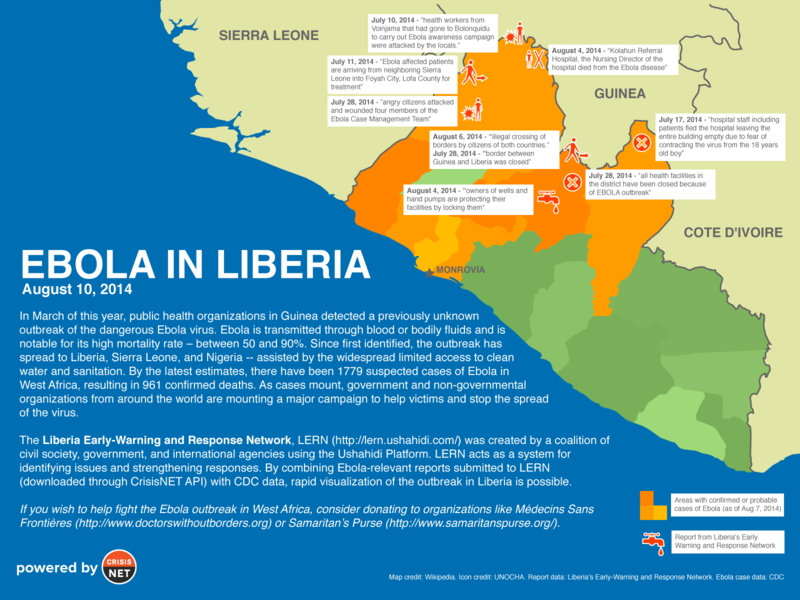

People have already started doing all manner of things with it, from visualizing the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, tracking Iraq’s growing refugee crisis, and monitoring the recent war in Gaza.

CrisisNET provides access to all of the data it collects, without censorship, and Albon is adamant that the service remains impartial. “We purposely take a very light touch on the data. For example, we don’t verify sources or check for hate speech. Some people might see this as a negative and a risk, but we do it on purpose. Why? Because we know from past experiences that some users want this kind of data to, for example, identify rumors after disasters or track racist comments during elections.”

There’s still much work to do, and CrisisNET is still in its infancy. But while a wider debate rages around the value of big data, Albon and his team decided to roll up their sleeves and simply get on with it. “We don’t know how people are going to use this data, and that’s what makes it so exciting. We’re learning on our feet, and we’re happy to be the providers, the enablers. The world will decide how valuable it all is,” Albon said.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Design & Innovation section, which looks at new devices, concepts, and inventions that are changing our world. Click the logo to read more.