What if London–or large urban spaces the world over–was given the status of a National Park? Guerrilla geographer Daniel Raven-Ellison thinks it’s an idea worth pursuing. As the small print on the Greater London National Park website notes, this National Park is still only a “notional” one. It’s an idea. But, as Dan points out with a glint in his eye, even official National Parks are notional parks in a way. Parks are something we humans made up. We can remake them too.

Last year, Dan visited all fifteen of the U.K.’s national parks with his son. As they crossed the various mountains and moors, rivers and streams, he started to wonder why London couldn’t be a national park too? By connecting the idea of a national park and a city, might we productively transform how we see both?

Dan wants us to unpick the politics which informs how some places are chosen to be National Parks over others, arguing it’s prejudiced against the people and wildlife of urban areas: “There’s a sense that somehow the wild has to be pristine to be valued. But if you’re an individual flower, or pigeon or fox. You’re no less wild. There are just fewer of you, and you’ve learnt to be in a city better than maybe other things. But that doesn’t make you any less valuable.”

Dan also refers to a vision of the city he’d picked up from Judy Lee Wong of the Black Environmental Network. She’d invited Londoners to see the Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty–a formal category in U.K. environmental policy–in their own doorsteps, to imagine pressing down on the layer of London made of buildings and roads to reveal the natural landscape underneath. “It’s there, behind all the buildings, between all the skyscrapers,” Dan adds. “It’s just about how you see the city and what you see.”

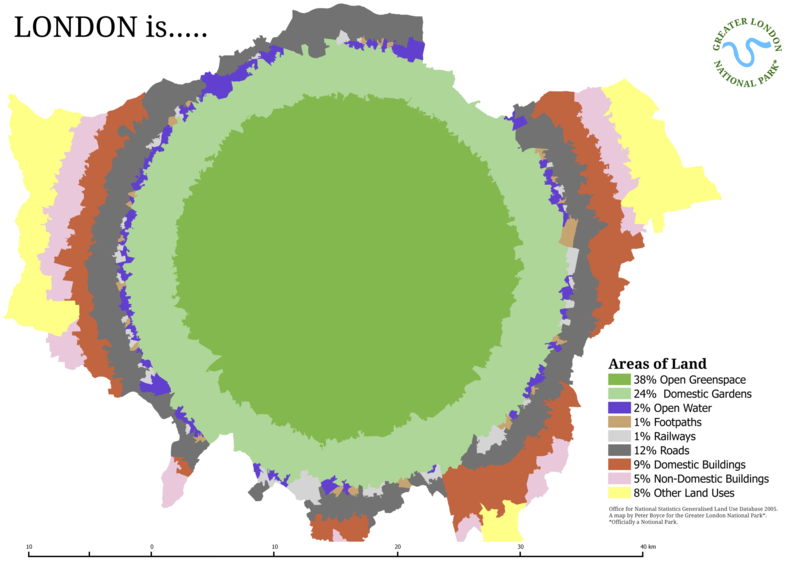

The team behind the Greater London National Park have produced maps highlighting how much green space there is, and have been working with students at Queen Mary University of London to photograph the city’s wild places and green infrastructure for a ReImagine London exhibition.

London is home to 3,000 parks, two national nature reserves, 36 sites of special scientific interest and 142 local nature reserves. 24 percent of the city is garden. The city started life as soggy marshland, surrounded by ancient forest. Residues of this forest still survive in pockets, with some of it registered as ancient woodland. The iconic London plane trees are young in comparison, only a few centuries old.

And then there are the animals other than humans. The record-breaking Peregrine Falcon, for example, or the endangered stag beetle. Pigeons, seagulls, bees, foxes, deer, seals, ducks, bats. Look carefully in St James’ Park, and you might see a black swan. There’s even some commercial farming, although Londoners do largely import their food, with an increasing number of community growing schemes and an established network of 30,000 allotments. South London has an underground farm in an old bomb shelter, and an edible bus-stop.

London has its own wildlife heritage too, with urban myths to give New York’s crocodiles a run for their money. The flocks of feral rose-ringed parakeets increasingly spotted in the West and South of the city, for example. They are sometimes explained as having descended from a pair that escaped the set of The African Queen, filmed in Ealing Studios in the early 1950s. Others think they came from birds released by Jimi Hendrix in Carnaby Street in the 1960s, or perhaps an aviary blown down in the 1987 hurricane.

If it all sounds a bit philosophical, it is. But, forged in the mud, bark, birdsong and insect bites of the city, the idea of the Greater London National Park can have very real impacts too. We need to see this urban wildlife, to help us protect it. But, just as cities need to remember ideas of conservation, there are things the idea of a city can offer environment too. “The interesting thing about cities is that they are about hope, and opportunity and potential,” Dan argues. There’s a way in which this idea of a Greater London National Park might help us imagine a greener futurism, rather than a metal and concrete one.

“London, 250 years after being a blueprint for the industrial revolution, could lead a very different type of revolution,” Dan excitedly adds, the glint in his eye back. He refers to the transformation of former industrial areas like Barnes, now a major wetlands center. “And then there’s all the things we can do in our gardens! 24 percent of London is gardens. There are 3.8 million gardens in London. If we were to all put holes in our garden fences then hedgehogs could penetrate further into the city.” As he told the Independent earlier this year, “Forget HS2 [a high-speed railway planned for England] let’s have HS3, a high-speed network for hedgehogs.” And that’s before we start thinking about the potential for urban beekeeping.

Dan’s going to be speaking at the IUCN World Parks Congress in Sydney next month, and is looking forward to discussing the idea in a more global setting. They’ve already had interest from cities in several other continents. “It clearly wouldn’t work everywhere,” he stresses, “but it could work in a few places.” At home, the team are actively lobbying the Mayor of London for support, determined to make it more than just a “‘notional’ park. The response they had from Natural Parks England was, essentially, that Natural Park Cities don’t exist yet, so get on with it–and they plan to.

They’re speedily accruing supporters, and Dan’s keen to talk to people–from any where in the world–about the idea and how it might develop. You can get in touch via their website.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Nature & Climate section, which looks at how human activity is changing the planet–for better or worse. Click the logo to read more.