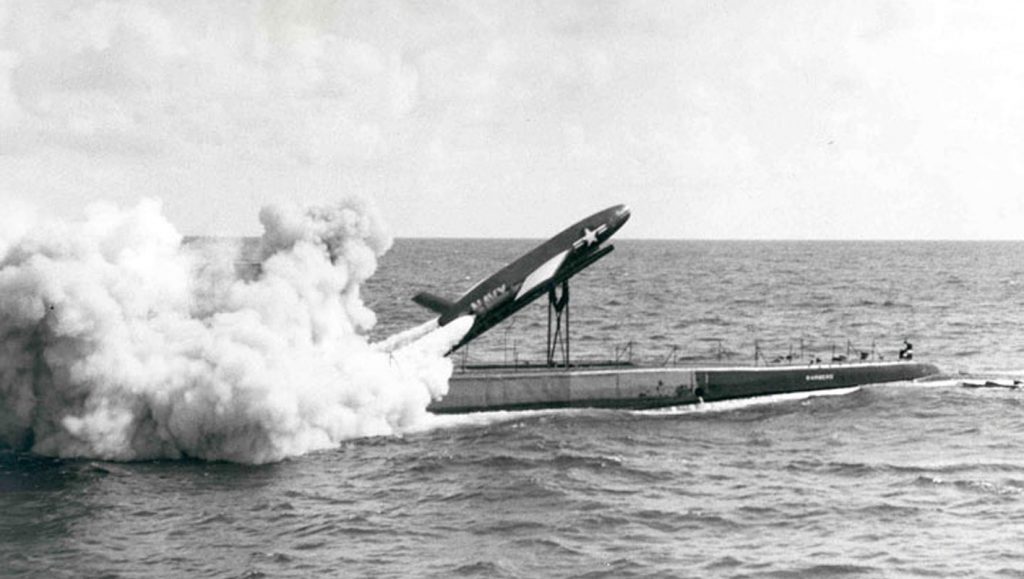

On June 8, 1959, shortly before noon, Arthur E. Summerfield squinted upward from the deck of the USS Barbero as a Regulus cruise missile arced into the sky toward the Naval Auxiliary Air Station in Mayport, Florida.

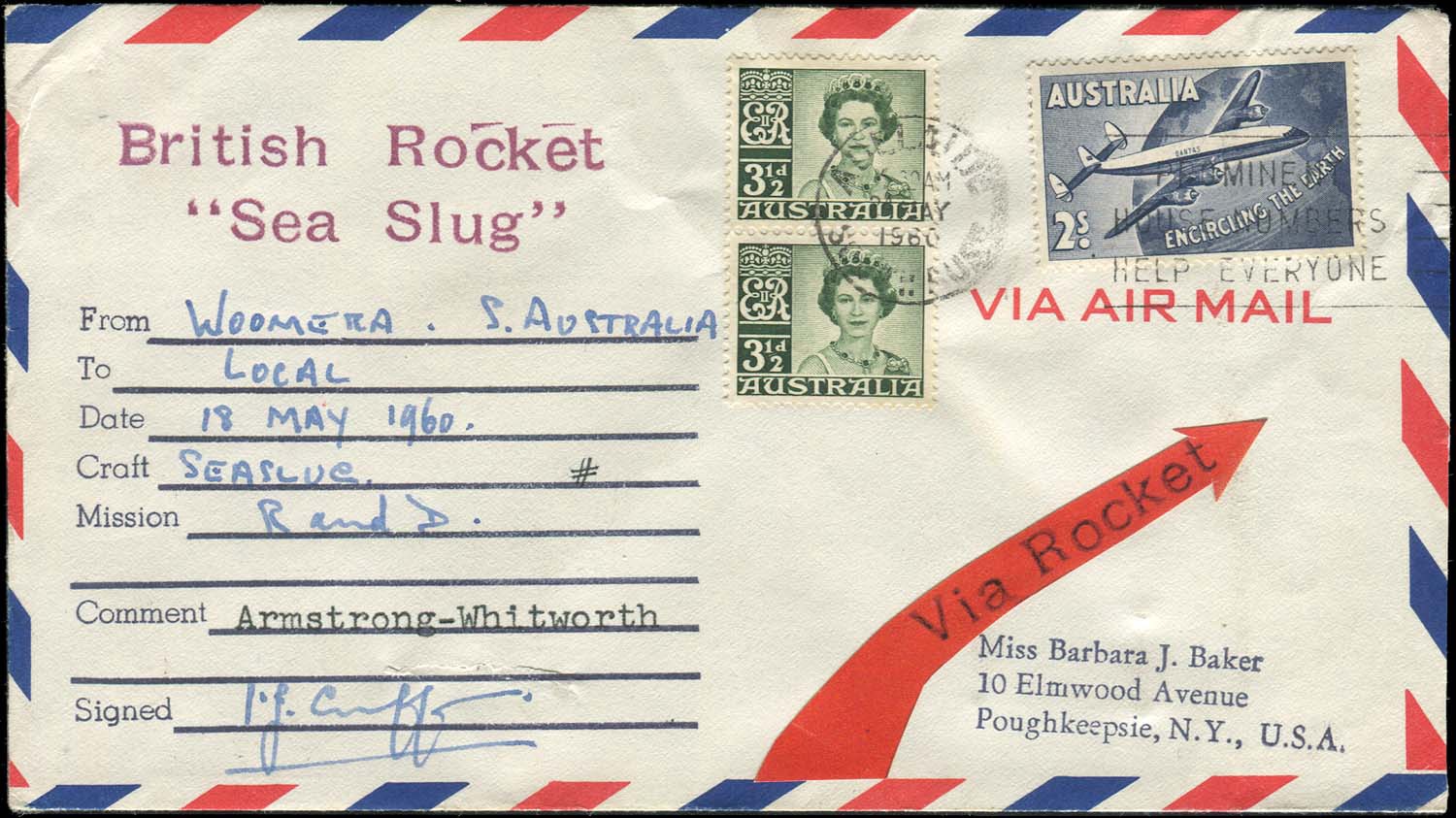

Normally, a cruise missile aimed at a military base would be cause for alarm. But in this case, the rocket’s payload wasn’t explosives–instead, a training warhead had been specially modified to house two containers carrying about 3,000 letters, each marked with a special stamp that certified them as the first to be sent by “missile mail.”

Summerfield was the United States’ Postmaster General, and he’d been working for seven years on modernizing the Post Office. When he was appointed to the role by President Eisenhower in December 1952, the mail system still relied on sorting and processing letters almost entirely by hand, and as a result, it had a poor reputation. Summerfield vowed to change this–both by introducing new technology and embarking on a significant public relations push.

Over the course of Summerfield’s tenure, he began a promotional campaign designed to highlight Post Office achievements; narrated a TV series called The Mail Story on the ABC network; mandated the adoption of a new red, white, and blue color scheme for all Post Office boxes, delivery vans, and equipment; and introduced mechanized mail-sorting techniques. But perhaps his most audacious proposal was the delivery of mail by rocket.

Twenty-two minutes after launch, the cruise missile and its postal payload landed safely at its destination, where it was opened, and its contents forwarded to the Jacksonville, Florida Post Office for further routing. Summerfield, upon witnessing the landing, said:

“This peacetime employment of a guided missile for the important and practical purpose of carrying mail, is the first known official use of missiles by any Post Office Department of any nation. Before man reaches the moon your mail will be delivered within hours from New York to California, to England, to India or to Australia by guided missiles. “¦ We stand on the threshold of rocket mail.”

He wasn’t entirely correct, but to understand why not we need to look back at the history of the technology, which stretches across the Atlantic Ocean to Germany at the beginning of the 19th century.

Projectiles have long been used to deliver mail. In medieval times, it was common to wrap parchment around an arrow and fire it short distances–into a castle, for example, to get a message through when the gates were shut.

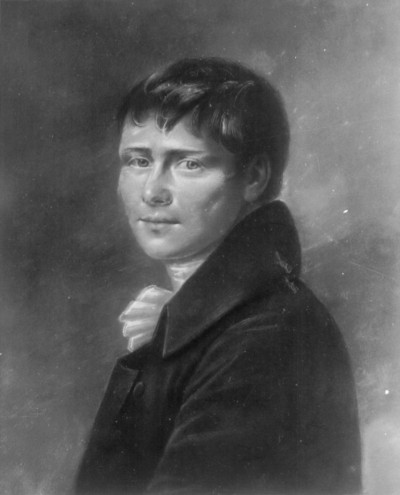

But the first person to suggest the use of more modern technology for mail delivery was the editor of the Berliner Abendblätter, Heinrich von Kleist. On October 10, 1810, he wrote an article under the heading “Useful Inventions,” calling for fixed artillery batteries to be aimed at soft ground and used to fire shells filled with letters.

According to his calculations, a network of such “mortar mail” batteries could be used to send a letter from Berlin to Breslau, 180 miles away, in just half a day. While von Kleist acknowledged that the recent invention of the telegraph was impressive, he considered it too slow to transmit anything of substance, and calculated that it would take 10 times as long for a similar letter to travel the same distance by horse.

Unfortunately, von Kleist’s recommendations were widely ignored. The next issue of the newspaper carried a letter from a reader stating that neither the electronic telegraph nor the mortar should be considered a “useful invention.” It continued that since most news is bad news, the only useful invention would be one that slows the mail down. As such, “mortar mail” was never attempted.

Later in the 19th century, on the far side of the planet, residents of Tonga experimented with attaching mail canisters to very basic “Congreve rockets” left over from the New Zealand Wars. These, the islanders found, made it easy to bridge the difficult reefs between Tonga and Samoa, but the failure rate was high–many canisters were never found, while others split on impact and were ruined by seawater. Instead, the islanders switched to the “postbuoy,” or Tin Can Mail–floating canisters that were dropped off steamers and could be collected by islanders in outrigger canoes.

It wasn’t until the late 1920s that the concept was resurrected–this time by Austro-Hungarian physicist Hermann Oberth. Oberth was one of the founding fathers of rocketry, alongside Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, who we recently profiled. Inspired by Jules Verne, like many scientists of the era, Oberth pursued his love of the subject despite many setbacks–including the rejection in 1922 of his doctoral dissertation as too “utopian.”

Oberth was a huge inspiration to 18-year-old Wernher von Braun, but his role in this story is as orator of a lecture he delivered in June 1928 at the German Society for Aeronautics and Astronautics, expounding on the possible use of rockets for the delivery of mail. He told the audience:

“The rocket seems suitable for transporting urgent mail over long distances in a very short time. The rocket would have to land by means of a parachute: some other means of transportation would then carry the apparatus to its precise destination. At a later date I would equip such a rocket with a powerful booster that would result in transoceanic ranges.”

The reception for his idea was warm, and by 1929, the U.S. ambassador to Germany was already discussing the legalities of transatlantic rocket mail with a German reporter. Detailed routing plans were drawn up and to many in attendance the idea of long-distance rocket mail seemed like an inevitability. Unfortunately, despite this optimism, the first long-range rocket, the V-2, didn’t lift off until 1942. When it did, it was carrying a deadly payload of explosives, rather than mail.

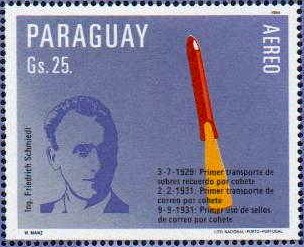

That didn’t stop other European rocket engineers from conducting several shorter-range experiments in the meantime. On February 2, 1931, Austrian scientist Friedrich Schmiedl launched a solid-fuel rocket carrying 102 letters over a mountain between the towns of Schöckl and St. Radegund–a distance of about 1.9 miles. It landed successfully, and Schmiedl followed up the launch with several rockets to other neighboring villages.

The sale of special postage stamps funded these experiments, as philatelists quickly became interested in collecting letters that had been sent by rocket–thereby funding further launches.

Schmiedl sketched out plans to expand the scheme, but the Austrian Post Office was unconvinced and passed a law in 1934 banning the financing of rocket mail experiments with the sale of stamps. Schmiedl continued using his rockets to collect meteorological data and for aerial photography purposes, but when the Second World War began, he destroyed his research documents over fears they’d be used for military purposes. After the war, he declined an offer to go to the United States to continue rocket research like von Braun, and instead worked on boat propulsion until he died in 1994.

At around the same time that Schmiedl was firing rockets over mountains in Austria, several other enthusiasts conducted similar experiments in Germany, Holland, Cuba, Australia, and the United States. In India, a rocket engineer named Stephen Smith completed 270 successful launches between 1934 and 1944, and unlike Schmiedl, he received much encouragement from Indian officials.

On one memorable occasion, Smith fired a rocket over a river in the Quetta region, which had recently suffered an earthquake. Attached was a relief parcel containing rice, grain, spices, cigarettes, and 150 letters. On another, he launched a rocket containing a pair of chickens called Adam and Eve (they survived the flight and lived another 18 months in a zoo), and on a third he successfully transported a snake named “Miss Creepy.” Unfortunately, the Second World War curtailed Smith’s experiments, and he died shortly after the war ended. Today, he’s considered the father of aerophilately in India, and a stamp was issued in his honor in 1992.

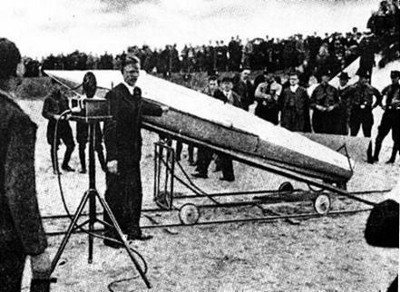

But perhaps the most notorious rocket mail pioneer was a German inventor named Gerhard Zucker. He spent 1931″”1933 touring his home country and showing off various rocket designs–while touting their suitability for mail delivery. At some demonstrations, he sold special envelopes that would supposedly be carried aboard his rocket flights, though there’s little evidence that any of these envelopes ever actually made it off the ground.

Most of his rockets failed to take flight, too. In one demonstration in 1933 in a town called Cuxhaven on the North Sea coast, the missile only managed a distance of 49 feet before coming crashing to the ground. The following winter he demonstrated his rocket to Nazi government officials, but no collaboration took place. He later claimed that they wanted him to carry bombs on the rocket, and he refused to do so.

Instead, Zucker made his way to Britain, where in May 1934 he exhibited some of his envelopes at the London Air Post exhibition. There, he convinced a photographer and stamp dealer to help in a quest to interest the British government in his rocket, using the same strategies he’d tried in Germany.

In the early morning hours of June 6, 1934, he successfully launched a test rocket to a height of about 2,625 feet from a hilltop on the Sussex Downs carrying a number of letters. A reporter and photographer from London’s Daily Express were present, and the headlines the next day announced “‘The First British Rocket Mail,” as well as a claim from Zucker that he’d soon be able to send regular post between Dover and Calais.

Around this time, the General Post Office in Britain was looking for a method to send mail over water during rough weather, and took notice of Zucker’s test flights. He was invited to prove his technology in Scotland, with Post Office staff asking him to transport mail between Scarp Island and Hushinish Point on the Isle of Harris–a distance of about one mile.

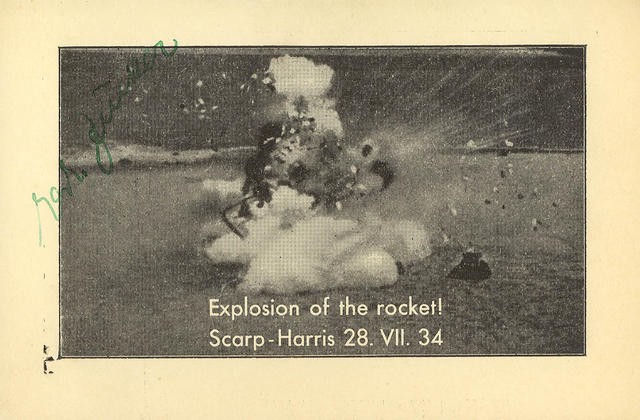

On July 28, 1934, the group arrived at the launch site and assembled the rocket, loaded with 1,200 pre-sold and highly-profitable envelopes. Zucker lit the fuse, but instead of shooting up into the air, there was a flash of light, a muffled explosion, and a cloud of smoke. Zucker apologized profusely and blamed the failure on the type of explosive used.

Three days later, on July 31, he tried again, packing a second rocket with the surviving envelopes from the first flight. Unfortunately, a similar explosion lit up the beach, and this time burning envelopes scattered the ground. The Post Office staff looked on unimpressed as Zucker rushed about trying to recover as many as possible–knowing that the scorched remains would be highly desirable among collectors.

A third and final attempt in Hampshire in December 1934 was also unsuccessful. Zucker’s excuse that the failure of this rocket was due to a gust of wind failed to convince the Post Office, which was looking for a solution that would work in stormy weather. To add consequence to an already bruised ego, the rocketeer was judged to be a “threat to the income of the Post Office and the security of the country” and promptly deported.

On arrival in Germany, the unlucky Zucker was met by the Gestapo, which immediately arrested him on suspicion of espionage or collaboration with Britain. He was threatened with incarceration or commitment to an asylum but managed to dodge both in exchange for a promise not to conduct any further rocket experiments.

After serving in the Luftwaffe during the Second World War, he moved across the border from East to West Germany and became a furniture dealer. He began experimenting again with rockets, until an accident occurred on May 7, 1964 at a demonstration in Braunlage in which three people were killed. In the wake of the tragedy, all non-military rocket launches in West Germany were banned.

Ironically, this ban directly resulted in the closure of a civilian spaceport in Cuxhaven, where Zucker had failed to launch a rocket three decades beforehand. At that demonstration, a local space enthusiast named Hugo Woerdemann had been so impressed by the technology Zucker was using that he began his own rocket experiments at a research center there–eventually touted as the “Cape Canaveral of Germany.” After the accident in Braunlage, however, the firing grounds in Cuxhaven were permanently closed; they are now a protected national park.

As for Zucker, he went back to furniture–but began trying to launch small mail rockets again in the 1970s, financed by the same old fraudulent envelope scheme. He died at home in 1985, though his exploits in Scotland–or some semblance of them–were turned into a 2004 film called The Rocket Post.

On balance, it’s hard to say whether Zucker’s contributions to rocket mail were positive or negative. His incompetence and fraudulent behavior had fatal effects for the technology in several countries, both metaphorically and literally. But his fondness for the spectacle of a launch inspired many more competent scientists down the path of rocketry, and similar envelope-selling schemes financed their experiments and yielded far better results.

Which brings us back to the deck of the USS Barbero on June 8, 1959. Summerfield was likely well aware of the checkered history of rocket mail and the actions of Zucker, though U.S. experiments with the technology, with a couple of notable exceptions, had been largely successful.

Just five years beforehand, in August 1954, a German-American science writer named Willy Ley had penned a lengthy article for Galaxy Magazine that charted the history of the technology, noting that the original trans-Atlantic rocket mail ambitions held by Hermann Oberth in 1929 were becoming increasingly irrelevant. He wrote:

“The mail plane needs only about eight hours to cross the ocean. Less than two years from now, the transatlantic mail plane will be turbojets requiring, say, six hours for the flight. And another two years later, this time might be reduced to five or even four hours. The long-range unmanned mail rocket has been effectively killed off by the fast long-range manned airplane.”

But Ley added that “missile mail” was a different story. The guided cruise missiles of the era, he said, could be controlled and even landed like an airplane at an airport where postal facilities already exist. He added that they could travel far faster than commercial planes. The article concluded:

“It looks as if a famous French saying might be adapted to read: La fusée postale est morte, vive le projectile postal!”

Those words were no doubt echoing in Summerfield’s mind as he gazed at the red, white, and blue cruise missile while it soared through the sky. It carried letters addressed to U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Postmasters General of all members of the Universal Postal Union, and various other government officials–including the defense chiefs that had made the test possible.

Unfortunately, those defense chiefs didn’t share Summerfield’s enthusiasm for rocket mail. They saw the experiment solely as a demonstration of U.S. missile capabilities–a way to prove to an increasingly belligerent Soviet Union that America was catching up fast. Only two years beforehand, a U.S. government report had indicated that the nation was far behind the Russians in terms of missile technology, and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev had challenged the United States to a “shooting match” to prove it.

As such, once the first missile had been fired, there was little desire for more and Summerfield’s lofty rhetoric on the technology would go unfulfilled. Perhaps he didn’t lose too much sleep over it, though. If you recall, the Postmaster General’s goal was not only to improve the efficiency of the U.S. Postal Service, but also its image among the public. Was the 1959 USS Barbero launch merely a publicity stunt? We’re unlikely to ever know for sure–Summerfield’s tenure as Postmaster General ended in 1961 when John F. Kennedy was elected president, and he died in 1972 at the age of 73.

The dream of rocket mail didn’t die with him. On December 3, 2005, XCOR Aerospace carried mail from Mojave to California City in a rocket-powered aircraft–marking the first time that a manned, rocket-powered aircraft was used to carry U.S. mail.

And technologists, like Mars Direct’s Robert Zubrin, believe that some form of rocket mail might become commercially viable in the coming years as reusable launch systems like those being developed by SpaceX become prevalent. In Zubrin’s book Entering Space, he discusses how such a system could allow for package delivery anywhere in the world in less than an hour.

In the meantime, though, we’re probably stuck with good old-fashioned air mail. At least until the drones take over, anyway. Von Kleist, the Tongans, Oberth, Schmiedl, Smith, Ley, Summerfield, and even Zucker would no doubt be happy that we’ll soon be able to once again adopt a military technology for more peaceful ends.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Above & Beyond section, which looks at our understanding of the universe beyond Earth. Click the logo to read more.