The history of music is one of tinkering. Think of any major modern instrument–keyboard, guitar, drums, saxophone–and it is the consequence of years of user adaptation.

But researchers at the Augmented Instruments Laboratory at Queen Mary, University of London are worried that the closed nature the technology many new instruments are built on is limiting our ability to fiddle. They hope their new hackable design, the D-Box, will help.

Traditional instruments start with a specific design, explained Dr. Victor Zappi, absentmindedly tapping the D-Box percussively as he spoke. “But that design changes a lot over time. People had the chance to play with these instruments, modify them, and these new features [were] passed on to other people, who did the same, and now we have a guitar! Or a piano! Or whatever,” he said.

Zappi also pointed to how we’ve transformed other objects into instruments. “The turntable was a way to play back music, but someone said, “‘I can use this in my own way and it sounds really cool,’ ” Zappi explained. “And it’s an instrument. A different way of appropriating the instrument, finding the features that were hidden.” We might also remove strings in a guitar, he suggested, or “prepare” a piano in the way German artist Hauschka does by adding ping pong balls, foil, or marbles to strings.

But Zappi and his colleagues are concerned that modern musical instruments–or rather the tech they’re based on–is hampering our capacity for musical expression. There are loads of people designing what might be thought of as new instruments today–or, more loosely, building technology to make sounds–but these largely digital interfaces are often very closed. They work for the initial designer, but it’s hard for other people to then go on and change them.

“These instruments are amazing pieces of engineering, cutting-edge technologies, but they are fixed. They are black boxes,” said Zappi. What we end up with is a load of parallel projects, he worries, each having a short life. “If you try to modify it, it’s very harsh, you might break it.”

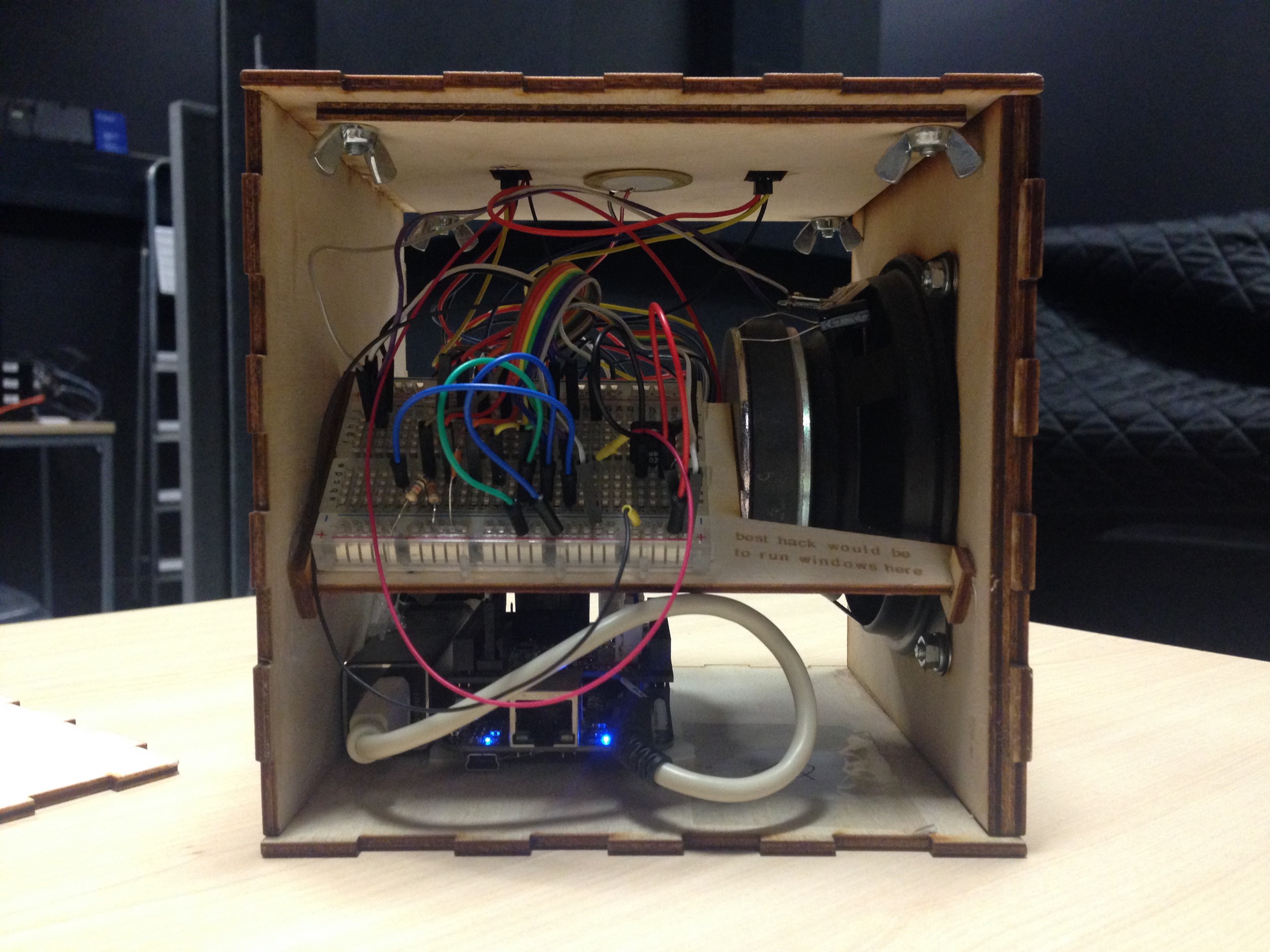

Though still in development, the D-Box hopes to offer something different, A small 15-centimeter wooden cube containing a battery, a speaker and embedded open-hardware, open-software miniature computer, it draws on ideas and expertise of circuit benders and hackers to ensure its design is as open to adaptation as possible.

“We have to design for the unexpected, design in a way that allows people to express themselves in a way we can’t foresee,” Zappi argued. “Because if you try to foresee, to design for possibilities, then some will be left aside.”

Also important for the Augmented Instruments Laboratory is that it’s easy to use. “You don’t have to be an engineer to change the way it works,” he said. That’s why they recently ran a study with 14 performers, who “came out with very different instruments. Some even came out with a different shape; they removed the enclosure and put in other things,” shared Zappi.

What the D-Box can do has limitations, but hopefully it’s much more open to development than other digital instruments. Even more, perhaps it will prompt the philosophy of hackable instruments to spread to other designs (boxed or otherwise).

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Fast Forward section, which examines the relationship between music and innovation. Click the logo to read more.