Three-dimensional, printed drone maps of Peruvian favelas. It sounds like something you’d make up to lure Vice hacks, but it’s serious–and it offers some quite real ideas for opening up processes of urban planning.

As Ph.D. student Flora Roumpani explains, the project is ReMap Lima. It applies new technologies to older ideas of participatory mapping, with the hope of uncovering otherwise “invisible” change and engaging communities with problem-solving in their local areas. It is a collaboration between several different units at UCL, working alongside a Swiss NGO, Drone Adventures; Fora Ciudades Para La Vida (Cities for Life Forum, Peru); and local community organizations in Lima. The project focuses on two different areas in Lima, one inside the city and a favela area in the outskirts.

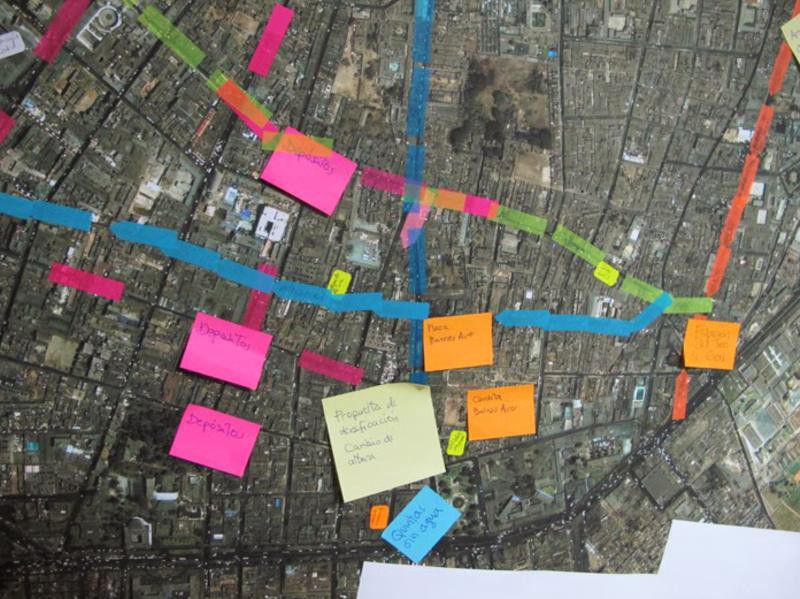

According to Roumpani, the favela areas are expanding so fast, they don’t have time for mapping. “So we use the drones to quickly capture everything–it’s really high resolution–and then present it to a community and get them to map their boundaries and talk about their problems,” she said.

It is, perhaps, odd to see drones referred to in a participatory mapping project–as they could be seen as anything but. It was striking that Roumpani laughed when she first mentioned them, as if there was something inherently funny about them, or something slightly awkward to be diffused. She explained that originally some of the people involved in the project were skeptical of the drones, if only because they carry some cultural associations that’d make the residents feel they were being monitored, or even targets of the military. But researchers were surprised by how much the local people took to them. “I think a huge part of it was that they knew what it was about,” Roumpani explained. They didn’t just go there and start flying drones above the literal and metaphorical heads of the local people. “The whole community was there with us. They participated in the throwing of the drones. It was fun, like a game. Kids wanted to fly them,” she said.

Roumpani also stressed that the mapping wasn’t just about drones. “We had people walking with smartphones, taking pictures to map boundaries and identify risks,” she said. They found falling rocks was key, as well as issues surrounding water inequalities and occupancy rights, especially relating to buildings of high cultural value. As well as helping to form the maps, locals could add notes on top of the drone data. This is where the 3D printing comes in. “Most people don’t have computers. So we’re going to create a physical model which will be used to project information on.”

Above all, ReMap Lima offers a chance to disrupt an overly top-down planning process. “The planner doesn’t really know what is going on in the city. He is just working from some data,” said Roumpani. “But if you actually work with people who live there you get some really valuable information. They know all the problems they have. They know what they need. They know all the little streets and where they go.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Metropolis section, on the way cities influence new ideas–and how new ideas change city life. Click the logo to read more.