What do you pack to eat if you’re going on a long trip–one that will last several years? It’s a problem that’s plagued sailors for millennia, but by the 19th century a new technology appeared to solve it: canning. It promised to keep food safe and edible far longer than any voyage.

At least, that’s what the members of the Franklin Expedition–the last major expedition of the Arctic north–thought as they set out in 1845 in search of the fabled Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific. When they left, they were equipped with several years’ worth of canned food.

None of them returned.

How they died has remained something of a mystery, but many now suspect that the food they ate may have been to blame.

The Franklin Expedition was one of a number of attempts to map the high Arctic while scouting the final, presumed route between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Explorers had plotted much of the area from both sides, but there was still a mysterious blank spot in the middle of the map–about 300 miles of what could have been coastline, open water, or impassable solid ice.

The task of filling in this void fell to a man who was well suited for the challenge. Rear-Admiral (retired) Sir John Franklin was an experienced explorer, and by later in his career had been elected as the governor of Tasmania (called Van Diemen’s Land at the time), where he served for seven years. His term as governor was interrupted when he was recalled to England after embarking on a journey to cross a poorly mapped part of the island; he got lost, which inspired consternation among the civil servants who ran Tasmania in his absence. By 1844, Franklin was back in England and looking for a new challenge. He was an obvious choice to lead a search for the Northwest Passage.

The expedition had been assigned state-of-the-art ships, HMS Terror and HMS Erebus, on loan from the government of the United Kingdom. They were fitted for the fierce weather of the Arctic with reinforced hulls, and had steam-driven engines that could push along at a speedy four knots (about five miles per hour) in calm weather. These had come from a railway engine, and were accompanied by a mechanism that allowed the rudder and propeller to be withdrawn and encased in iron shields to protect them from the ice.

There were also over a thousand books onboard, and enough tinned and other food to last three years. The whole enterprise was a demonstration of the British Empire at its finest: a crew of brave men led by an experienced explorer who knew the territory; an expedition equipped by the Admiralty with huge quantities of supplies and the latest in equipment. What could possibly go wrong?

Arctic expeditions at the time were long adventures. The usual approach involved sailing as far as possible in the short Arctic summer, then hunkering down for the long winter–letting the ship freeze in the ice until the return of summer melted it and freed the vessel. On a ship that was strong enough to withstand the pressure of the ice, this worked well. Often, expeditions were at sea for several years, sailing and waiting out the weather in cycles until they completed their objectives. They were literal voyages into the unknown, and in the days before radio (and too far from land for carrier pigeons) it wasn’t unusual to hear nothing from a ship until a few days before it sailed back into home port for a heroes’ welcome.

The Franklin Expedition never sailed home, though. After a few encounters with other ships on the way to the Arctic in 1845, it vanished, leaving no survivors and no indication of their fate.

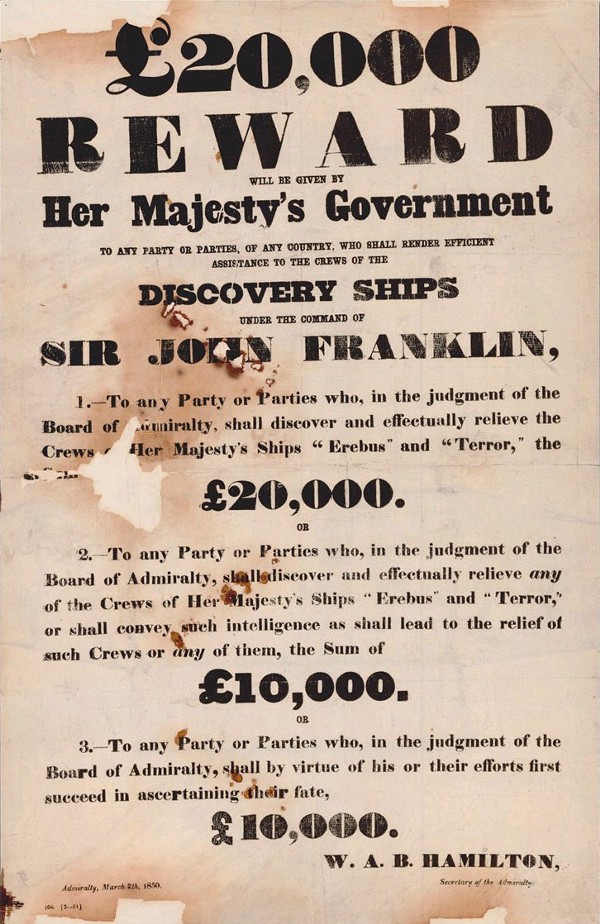

Franklin’s wife was the first to raise alarm in 1847, when she began asking the Admiralty to send an expedition to search for her husband. Knowing that there had been food aboard to last at least three years, it declined to do so until 1848–when it posted a sizable reward (£20,000, equivalent to about £2 million today) for anyone who could find and save the ships.

Vessels sailed in from the east and the west, and an overland expedition down the MacKenzie River tried and failed to find anything. It wasn’t until 1850 that a mounted expedition encountered a few telling signs; and it took several more voyages for the first real facts to emerge in 1859, thanks to conversations with Inuit hunters, and the discovery of relics and scattered written notes left by the crew of Terror and Erebus.

Here’s what became clear: The expedition had failed utterly. By 1846, both ships were firmly trapped in ice and the crew had begun to die. That alone wasn’t unusual, as most Arctic expeditions endured their share of fatalities from the weather or accidents. But this expedition seemed to suffer more than most. Franklin himself died in 1847 from unknown causes; his grave has never been found.

After a year and a half, the ships had been iced in for so long that by then the crew members knew a short Arctic summer wouldn’t free them. The pressure of the sea ice was beginning to crush the ships, and the expedition would have to find another way out. In a note scribbled on the margins of an earlier message placed under a rock cairn, a crew member wrote that by April 1848, 24 seamen were dead and that the survivors were going to walk south toward the distant Back River in Canada, where they hoped to reach a trading colony. They never made it.

The fate of the walkers is yet unclear. Occasional encounters with Inuit hunters over the next few years revealed a devastating tale of starvation and death, with reports of cannibalism among the survivors. Bones recovered from a site where they had camped after abandoning the ships indicated that at least 11 people died there, and that–according to the anthropologists who analyzed them–there were marks consistent with cut flesh. They concluded:

“Cut marks on approximately one-quarter of the remains support 19th-century Inuit accounts of cannibalism among Franklin’s crew.”

But maybe it wasn’t lack of food that doomed them.

The same analysis pointed to something else. The bones contained high levels of lead.

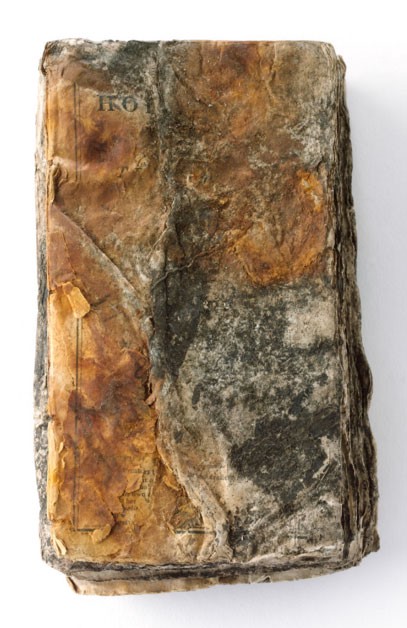

That wasn’t the first time lead had been found, either. A 1984 expedition had excavated the graves of three of the first crewmembers to die in early 1846 on Beatty Island. Samples from their bones also contained high levels of lead. The corpses were remarkably well preserved, appearing as if they had been in the ground for a few days rather than 138 years. In the book Frozen in Time, anthropologist Owen Beattie and writer John Geiger describe how the corpse of Petty Officer John Torrington, who died on January 1, 1846 at the young age of 20, looked:

“John Torrington looked anything but grotesque. The expression on his thin face, with its pouting mouth and half-closed eyes gazing through delicate, light-brown eyelashes was peaceful.”

The autopsy revealed that Torrington had probably died of pneumonia, a common killer in the bitter cold of an Arctic winter. But there was still that lead–and, after some searching, Beattie and others found what they thought was the culprit: the canned food the crew had brought with them.

Although the expedition had the best equipment available, the food had not been ordered until seven weeks before the crew was due to sail. The supplier who produced and canned it rushed to finish the job, sealing the cans poorly with lead solder that was exposed to the food inside. Beattie believes this means some of the lead could have leached into the food, slowly poisoning the crew.

Judging from those found in one of the expedition camps near the graves on King William Island, the book describes how poorly constructed some of the cans were:

“Beattie had seen photographs of food tins from various British Arctic Expeditions and had handled a few, but as he picked through the tins from Franklin’s expedition, he saw that they were different. The lead soldering was thick and sloppily done, and had dripped like melted candle wax down the inside surface of the tins.”

Beattie concluded that the crews of the Erebrus and Terror were indeed slowly poisoned by the very food that kept them going through the cold, Arctic winters.

Symptoms of lead poisoning are unpleasant, including memory loss, seizures, and fatigue. While the poisoning itself doesn’t usually kill the victim, it can leave sufferers more open to other diseases by causing anemia and suppressing the immune system. Even if just a few of the crew were poisoned by lead, the effect of so many deaths on the morale must have been devastating.

By the time the crew abandoned the stricken ships, the vessels were decimated. Of the 129 who had set out, 24 were dead by April of 1848–nearly 20 percent. To make things worse, many of the deceased were the officers who commanded the expedition and were experienced in Arctic survival. The survivors left walked hundreds of miles through the bleak Arctic, only to die in its frozen wastes.

Although Beattie and others build a compelling narrative for lead as the expedition’s main failure, others are still skeptical. In a recent article for the Polar Record, several scientists note that most people in England during the Industrial Revolution were exposed to high levels of lead, and that the amount of lead found in the tested bones varied widely. However, they do concede that some of the crew would have likely been affected:

“Comparison of the estimated lead burdens with present-day data that associates lead with cognitive and physical morbidity suggests that a proportion of the crew may have experienced few or no adverse effects whilst those with higher burdens may have suffered some significant debility.”

Another possible culprit beyond tin canning is the system that purified water for the ships’ steam engines. William Battersby describes this as a potential lead source in a paper he presented to the Hakluyt Society. The engines were designed to run on fresh water, so waste heat from cooking in the galley was used to distill seawater. The same system also likely supplied water for the crew’s cooking, particularly for making bread. It was water that had traveled through lead pipes. As Battersby notes:

“Both ships carried 136,656 pounds (62,041 kilograms) of flour to be baked into the ships’ biscuit or bread while on the voyage “¦ nearly 90 percent of the bread or biscuit eaten on board was baked using water from the ships’ tanks. When hot food is prepared using water which contains lead, some water is boiled off as steam but all the lead and any other residue remains in the food. This means that bread and biscuit prepared on board could have had a high lead content.”

We might actually get to find out if Battersby’s theory is correct. In 2014, an expedition located the wreck of the HMS Erebus on the Arctic seabed, where it had lain since it was finally crushed by the ice. The team that found it recovered the ship’s bell, and another expedition in 2015 revealed that the ship is in remarkably good shape. Further exploratory expeditions are being planned.

Although what exactly killed the crew of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror is still the subject of much debate, some things are obvious. Despite the experience of the crew members (and Franklin himself), they were sailing into an inhospitable place with resources that were, at the very least, untested, and, at worst, severely compromised.

The lead in the food or water may not have been the direct cause of every death, but in an unforgiving environment like the Arctic, you don’t get a second chance. The lesson of the Franklin Expedition should be that it’s never a wise strategy to cut corners on how you store your food.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Histories of”¦ section, which looks at stories of innovation from the past. Click the logo to read more.