The things that define something as someone–as a person–are complex, contested, and mutable. Thinking about the moral, legal, and philosophical arguments around who does and does not get to be a person is a crucial step as we move ever closer toward the birth of the first truly sentient machines, and the destruction of the most highly sentient, endangered animals.

What level of sophistication will artificial intelligences need to attain before we consider them people–and all the rights that entails? And at what point on the spectrum of intelligence will we be creating machines that are as smart, and as deserving of legal rights, as the sentient animals we’re driving to extinction?

“The same arguments we’re making now on behalf of chimpanzees are the same arguments that will be made when, and if, robots ever can attain consciousness,” said Steve Wise, president of the Nonhuman Rights Project.

For years, NRP staff has mounted legal challenges on behalf of nonhuman animals, hoping to use legal, moral, and scientific arguments to change the status of high-order, nonhuman animals from “things” to “persons.”

The chimpanzee shares about 99 percent of its DNA with humans–which means that, surprisingly, they have more genetic similarities with us than they do with gorillas. Like humans, chimpanzees have only a small number of offspring, with females usually giving birth once every five years of sexual maturity, and on average rearing only three children to full adulthood. In social groups they perform cooperative problem solving, teach and learn from one another, and use rudimentary tools; mentally they have at least some concept of self, an IQ comparable to a toddler, and can actually outperform humans on certain cognitive tasks.

Chimpanzees also display friendship, joy, love, fear, and sadness through body language clearly readable by human emotional standards. When exposed to stress and trauma, they have behavioral disturbances that, in some cases, meet DSM-IV criteria for depression and PTSD.

So, then, here is a question that’s all but unavoidable in a discussion of animal personhood: Is it all right that we’ve collectively decided such a creature does not deserve any of the same legal rights–not even a small subset of the rights–that a human being has?

“For many centuries, the essential distinction between entities has been that of those who are things–who lack the capacity for any legal rights–and those who are persons, who have the capacity for one or more legal rights,” Wise said. “We’ve spent many years preparing a long-term, strategic litigation campaign “¦ where we put forward arguments that elephants or chimpanzees or orcas ought to have legal rights, in fact ought to be legal persons, in terms of the sorts of values and principles which judges themselves hold.”

In a case last year, one of their most high profile to date, lawyers from the Nonhuman Rights Project brought an argument to the New York City Supreme Court, which hinged on whether the writ of habeas corpus applied to two chimpanzees being held for use in medical experiments. The presiding judge ordered that the president of Stony Brook University, where the chimps were held, appear in court to argue against the case that they were being “unlawfully detained”–which by extension would imply that the chimps were legal persons with a right to due process. Although the judge later amended her order to remove the words “writ of habeas corpus,” and clarified that she had not intended to suggest that chimps have legal person status, it was an important milestone nonetheless.

The reaction from the public around NRP initiatives, Wise noted, has been largely positive–with the biggest resistance often coming from judges who are sometimes affronted by the unusual nature of the ensuing litigation. Meanwhile, he said, in recent times it’s becoming more common for artificial intelligence researchers to contact him after hearing about his work.

Nick Bostrom, philosophy professor at Oxford University and director of the Future of Humanity Institute, is well known for writing about issues surrounding the development of superintelligent AI. Rather than debating the point at which an AI might be considered sentient, his work assumes that this will certainly happen at some point in the future, and instead questions how we should act in the present with the knowledge that we will eventually live alongside artificial minds exponentially more powerful than our own.

Though Bostrom’s work is often cited in terms of the potential dangers of AI, he’s also interested both in the idea of whether we should assign rights to artificial intelligence, and how those rights would be qualitatively different than the type of rights a natural person requires.

“If you had something that was exactly equivalent to a human, except running on a computer–something like a human upload–then there are still many novel ethical issues that arise,” Bostrom said. “For example, a human simulation might want to copy itself, but we would not want to allow it freedom to infinitely reproduce, or else it could theoretically expand to take up all available resources. So in a world in which this exists, we cannot have both reproductive freedom and a welfare state that guarantees a minimum standard of living for everybody, since the two are mutually incompatible.”

The idea of digital reproduction would also bring up entirely new problems for political representation, Bostrom noted, as the idea of “one person, one vote” would clearly not be democratic in a constituency of self-replicating voters. (Maybe in the future digital beings might have “legal” and “illegal” status, in much the same way that humans who enter a country without government permission cannot vote, claim health insurance, etc.)

In order to enjoy the best quality of life, a human upload would probably demand that it live on a fast computer, that never be paused or restarted without consent–permissions which could, conceivably, be the kind of things that will one day be enshrined as legal rights for sentient artificial beings.

At the moment, these debates are wildly speculative. But as Bostrom argues in his book Superintelligence, the main advantage we have over future AIs is simply that we exist here, now, and can shape society to map out their rights and responsibilities before they arrive–while also building as many safeguards as we can against direct competition with them. From that perspective, perhaps it would be foolish to throw away our head start.

“When we first think of artificial intelligence, our mind often goes to popular culture, science fiction, and the idea of an android–something like Data from Star Trek,” said Max Daniel, co-executive director of Sentience Politics, a think tank producing policy on topics linked to morality and the reduction of suffering across all sentient beings.

“This is a being that can talk, and is in many ways similar to a human: It can communicate with us, complain if we mistreat it, and so on. But what is perhaps much more realistic to assume–and this is a concern that the German philosopher Thomas Metzinger has raised–is that the first digital beings would be much more limited in their abilities, in fact much closer to nonhuman animals than humans, and so could not properly signal to us whether they were suffering.”

Because of this, Sentience Politics is advocating for a clear set of ethical guidelines around research on artificial intelligence, including putting careful controls in place to avoid a situation in which a sentient being is unknowingly created as part of a machine learning project. As part of this initiative, Daniel mentioned the importance of implementing an “excluded middle” policy, first articulated in a philosophy paper by two researchers at UC Riverside, Eric Schwitzgebel and Mara Garza. Essentially, the excluded middle policy states that we should only create artificial intelligences whose status is completely clear: They should be either low-order machines with no approximation of sentience, or high-order beings that we recognize as deserving of moral consideration. Anything in the ambiguous middle ground should be avoided to cause suffering.

Which raises the question: How do we differentiate between an artificial intelligence which learns to respond as if it is thinking and feeling, and one which is genuinely able to think and feel? What standard of proof would we ask for?

Provided we accept that it will one day be possible to create machines which experience some level of sentience, then giving them the right to ethical treatment seems uncontroversial. But what about rights that go beyond the scope of avoiding suffering and into the domain of personal fulfillment–the right not just to a life, but to one that includes liberty and the pursuit of happiness?

Before we continue any further, we need to step back for a minute to look again at how we define a “person.”

From a legal standpoint human, human beings are natural persons capable of holding legal rights and obligations. However, many present legal systems–like that of the United States–permit the existence of other types of legal persons, which are not flesh-and-blood entities but may nonetheless be granted personhood rights.

Take, for example, corporate personhood, where the legal entity of a corporation–and not just the human beings which comprise it–can own property in its own name or be sued in a court of law. Sovereign states also exist as persons under international law, and in certain exceptional cases other natural entities can also be persons, such as in New Zealand where theWhanganui River was granted personhood after campaigning by indigenous activists.

“Personhood is a legal status for which sentience is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition,” said Michael Dorf, professor of law at Cornell and author of a recent book onabortion and animal rights. “It’s not a necessary condition, because as a matter of law artificial entities like corporations can have personhood; and it’s not a sufficient condition because sentient animals, even those with advanced capabilities, lack personhood.”

Additionally, Dorf said there’s a tendency to think that personhood is an all-or-nothing position with regard to rights, but this is not necessarily the case. “It’s actually possible to have rights and responsibilities à la carte: For example, infants are persons before the law but lack some of the rights an responsibilities that competent adult persons have–such as they can’t vote, but then conversely can’t be responsible for criminal acts.”

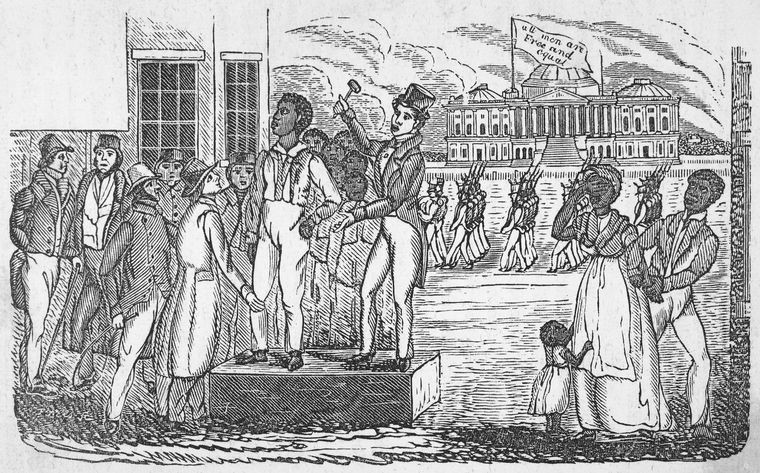

So a legal person need not have the full set of rights of a natural person–and though it’s tempting to claim self-evidence that all human beings have natural rights, as the Founding Fathers did, historically there was nothing certain or inviolable about the fact that all human beings should have full personhood.

From start to finish, the trans-Atlantic slave trade accounted for the kidnapping of 12.5 million Africans from Africa. Of these, an estimated 450,000 Africans were taken to the United States; in 1860, during the last recorded census before abolition in 1865, the number of African-Americans considered to be the legally owned property of another person totaled just short of four million.

The first Africans were brought to the Virginia plantations in 1609, but it took 50 years for the institution of slavery, and the status of slaves, to be legally codified. Since the British common law used at the time gave protections for persons that would have been incompatible with the brutal punishment slave masters administered, the 1669 Act About the Casual Killing of Slaves clarified that causing the death of a slave should not result in prosecution for murder, since it was effectively no more than the willful destruction of one’s own property.

The fact that ownership and sanctioned murder of another human being was a foundation of American history should show us just how personhood is a concept that has so often been defined in the interests of dominant power groups. The history of the feminist movement likewise shows the struggle, hundreds of years long, for women to enjoy the same legal rights as men. Lest we forget, until roughly 150 years ago, married women had no legal right to own property. There are still almost 1.5 million Americans alive today who were born before the 19th Amendment guaranteed women the right to vote.

Personhood, then, is by no means a fixed category; but in the present day we tend to think of it as something that is innate in all humans, without needing a great deal of justification. In trying to evaluate the nature of our shared humanity, arguments on the basis of intelligence–the capacity tothink–are quickly dismissed, since we know that there is huge variation within our species, and the suggestion that someone with a low IQ is less human is abhorrent. More often we veer toward a description based on sentience: the capacity to feel, particularly in a complex, emotional way.

Fully describing the nature of sentience among humans is hard enough–interrogating the nature of “the human condition” has been a staple of philosophical thought from time immemorial and shows no signs of being exhausted as a topic. So how do we begin to assess the nature of self, being, and sentience of minds which are artificially created? When will we reach a point that we perceive inorganic beings as possessing the capacity to feel?

For a long time the gold standard of artificial intelligence was the Turing Test, in which success or failure was defined by a computer’s ability to talk with a human partner in such a way that the human was unable to identify it as a machine. But today, when we regularly converse with phones so smart they’ve even fooled students of artificial intelligence, it has become ever more apparent that mimicking language is not the same as thought.

But the central point to consider in discussing robotic sentience is not the sophistication of any system that we have currently built; it is that we have the ability to build systems which are able to learn. Many applications of artificial intelligence we encounter online, from chatbots to image tagging,employ artificial neural networks, a form of machine learning inspired by the design of biological nervous systems.

Given a large enough dataset and enough time to learn, neural networks are able to develop models which will allow them to carry out complex tasks with uncanny accuracy–such as recognizing faces, transcribing speech to text, or writing plays in iambic pentameter–without having been specifically programmed to do so. It’s perfectly conceivable that as processing power increases and the range of available data on human behavior grows, neural networks will be created that are able to form some approximation of what it is to be human, and to communicate their own hopes and fears in a human-like way.

The law, as history attests, should not be set in stone. Besides being a collection of rules to help us govern ourselves, law represents a repository of knowledge about how the world works, and how we as a society should respond to issues around which there may be dispute. In this sense, the process of creating new laws, and specifically of allocating new rights to sentient beings which previously had none, can be seen as a process of increasing the level of compassion embodied in our social institutions.

We don’t necessarily need to exhaust every argument for and against giving certain animals personhood to conclude that they are deserving of the benefit of the doubt; there is no downside here to being overly generous with our compassion. Likewise, though the debate on rights for artificially sentient beings may seem abstract and theoretical at present, we don’t lose out by trying to map the route of least harm ahead of time, especially given the rate of technological change in this field.

In a book set out as a manual for living with conviction in challenging times, the political activist Paul Rogat Loeb wrote: “We become more human only in the company of other humans beings.” As an addendum, maybe a conviction to act morally with regard to all beings–especially those that differ greatly from us–is ultimately something that makes us the most human of all.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Identity section, which looks at how new technologies influence how we understand ourselves. Click the logo to read more.