It’s been almost 26 years since Tim Berners-Lee invented the web. Inspired by a tweet from HWGTN reader Ernie Schell, we’ve found five weird ways of connecting us that, for various reasons, never became as big as the World Wide Web.

1. Pasquino and the Roman Talking Statues

Sixteenth-century Rome was a hotbed of intrigue and gossip, but being caught gossiping was a potentially fatal risk. So, one way of sharing the latest news and rumors was to post anonymous messages on the many statues around the city. One statue of a mythical Spartan king was nicknamed “Pasquino” in honor of a renowned local gossip who once worked in the Vatican; the notes attached to this statue became known as “Pasquinades.” When the Vatican posted guards by the statue to stop the anonymous messages, locals started posting messages to Pasquino on other statues–and the conversations between them are still going on today. If you’d like to know more about ancient social media like this, we recommend Tom Standage’s brilliant book The Writing On The Wall.

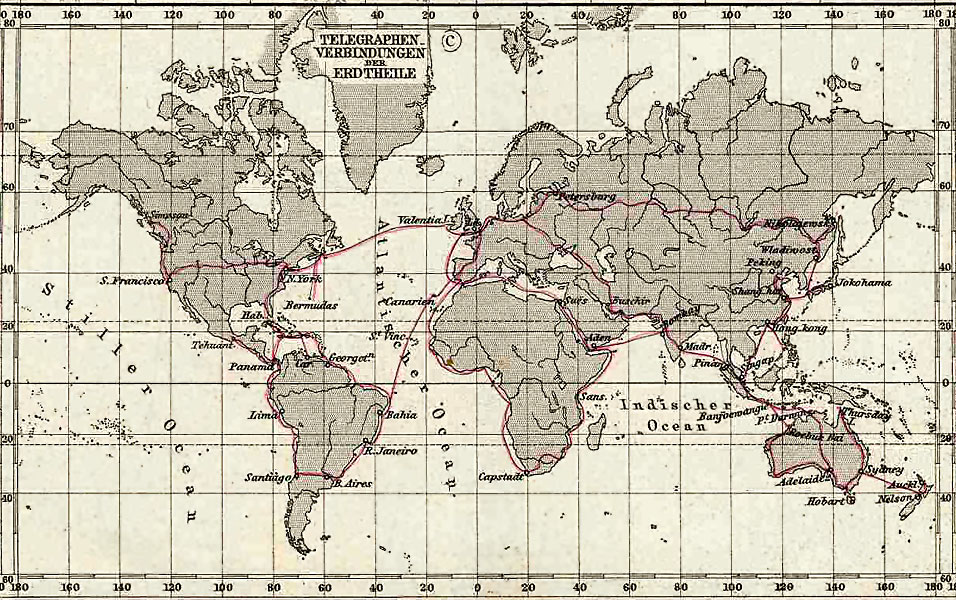

2. Claude Chappe’s Optical Telegraph

Claude Chappe was a French inventor and politician whose search for a way to speed up news about the French Revolution led to Europe’s first communication network. His experiment involved pendulum clocks at 10-kilometer intervals with synchronized hands. Operators could set a chime when the hand passed one of 10 numbers, indicating that number as part of the message. When this proved too limited, Chappe tried five large wooden panels that could be open or closed, offering 32 possible combinations. Finally, a semaphore system using a horizontal beam and arms that could be set at different angles provided hundreds of combinations. The system rolled out across France and neighboring countries, allowing Paris to receive messages from the front line in less than an hour. Despite the invention of the electrical telegraph in the 1830s, France–showing a stubbornness that would resurface in the 20th century–stuck with the optical version until the network finally shut down in 1852.

3. Telefon Hirmondo

After the invention of the telephone in the late 19th century, some entrepreneurs predicted its future would be not in person-to-person communication but as a broadcast network tool. “Telephone Newspapers” launched across the globe, offering a one-way telephone-listening device in your home for a monthly subscription. The Telefon Hírmondó in Hungary was one of the most successful, with over 15,000 subscribers by 1907. At various times during the day you could pick up the receiver and listen to a schedule of live news, opera, and financial reports piped down the network from a studio in central Budapest. The rise of radio in the early 20th century led to the service’s eventual demise, although early broadcasters adopted one of its innovations–an hourly programming schedule–that is still in use across TV and radio today.

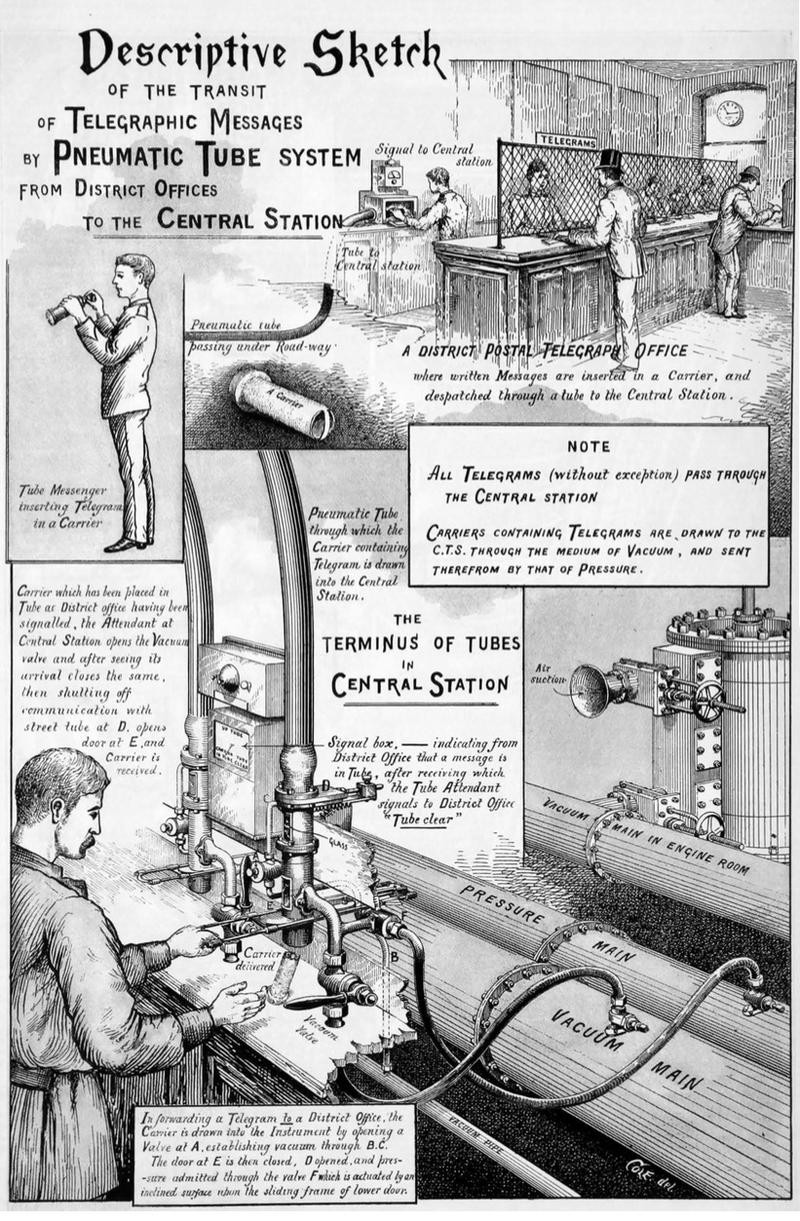

4. Pneumatic Tube Networks

Although the electrical telegraph did connect the world in the 19th century, it was limited in bandwidth and could only be used to send text messages. In 1854, chief engineer of the Electric Telegraph Company in London Josiah Latimer Clark patented his method for “conveying letters or parcels between places by the pressure of air or vacuum,” and established the London Pnuematic Despatch Company. The first line, from Euston Station to North West District Post Office in Eversholt St., London, carried mail bags on small rail cars. Although pnuematic networks were limited by the need to generate enough air pressure (and the small problem of messages getting stuck deep in the tunnels), they have seen many applications, including transporting hot meals around Berlin, sending money and goods around supermarkets, and connecting NASA engineers working on the Apollo missions. Even transport innovator (and real-life Tony Stark) Elon Musk is jumping on the pneumatic tube bandwagon with his Hyperloop proposal, which aims to connect Los Angeles and San Francisco in under 35 minutes.

5. Minitel

In the 1970s and 80s, the French echoed the story of Chappe and his optical telegraph by building a France-only version of the Internet. Developed as part of President Valerie Giscard d’Estaing‘s commitment to big infrastrucutre projects (which also gave France the TGV train and investment in nuclear power), the Minitel was a telephone-based video/text service offered to every France Telecom subscriber. By the late 1990s, Minitel had over 25 million users and 26,000 services, including holiday bookings, banking, chat rooms, and, of course, pornography. As with Chappe’s optical telegraph, Minitel faced competition from another global network–the World Wide Web–and on June 30, 2012, exactly 30 years after its launch, it was switched off.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our The Internet section, where we report on the past, present, and future of the information superhighway. Click the logo to read more.