The first robotic musicians are already almost 1,000 years old. They were mechanical bell-ringers, attached to the Cosmic Engine–a 33-foot clock tower built by Su Song in China between 1088 and 1092. The robots chimed the passing hours with a series of gongs and bells but were dismantled in 1127 by an invading army.

History doesn’t record whether the town squares and markets of the time filled with human bell-ringers complaining about being deprived of work, but at some point between then and now, “Robots are taking all the jobs!” became a very real state of affairs. And music is no exception.

In the last decade or two, robots (or, if we’re being precise, algorithms, but robots is more fun to say) have helped humans write music in software like Ludwig, Vocaloid, AthTek Digiband, and Microsoft’s widely mocked SongSmith. But now, the technology is reaching a point where the AI doesn’t need human assistance anymore–which will come as a nasty surprise to those people who assumed they were safe from robotic interlopers because they’re in a “creative” profession.

Already, Japan has a touring pop star–Vocaloid’s mascot Hatsune Miku–who is entirely digital. Her name, loosely translated, means “the first sound from the future,” and she performs as an animated projection. Play one of her recordings for someone who doesn’t know she’s a robot and see if he or she can tell what’s unusual about it.

To date, though, every job lost to technology has been replaced by new jobs configuring that technology–and music is no different. At least some of the artists of the future won’t lay down notes on a stave or play instruments directly. Instead they’ll work setting parameters for robotic songwriters to operate within. It’s no less creative a task, as any electronic music producer will tell you, but some of us might have to rethink what we consider to be a musician.

How would a robot soundtrack an airport? Earlier this year, in a competition aptly called Music for Airports, the city of Rijeka in Croatia called on musicians to pull together arrangements suitable for play at their local, international airport. Many of the entries, as contest coordinator Michela Magas from Music Tech Fest put it, involved “amazingly talented human beings brilliantly directing automatons.”

The name of the competition, as some of you will no doubt already recognize, bears a remarkable similarity to Music for Airports, Brian Eno’s sixth studio album, which was conceived during a flight delay in Cologne in the mid-1970s. Uninspired by the soundscape of the airport, he hit upon the idea of using phased tape loops to defuse the tense atmosphere, inducing calm and a space to think. Hit play on the video below, and you’ll be able to enjoy it while you read.

The concept of background or “furniture” music had already existed for decades, if not centuries, but Music For Airports was the first piece of music to be called “ambient.” Eno wrote in the liner notes of the album that the name refers to how it exists on the “cusp between melody and texture,” and could be either “actively listened to with attention or as easily ignored, depending on the choice of the listener.”

Since the 1970s, the popularity of ambient music has blossomed. It’s used in shopping centers, on public transport, in hospitals, and more. We hear music everywhere we go, and most of the time we barely notice it. Which, of course, is the point. But someone has to create all that ambient music–and it’s already become a job for robots.

Some ambient music today doubles as “generative” music–which is another word for robots that write music based on data. That data either comes from input they get from sensing the world around them or a collection of algorithms and random number tables.

“It’s very much about a stage of impermanence,” said electronic musician Robin Rimbaud. “Works that [are] relived many times over and offer new readings upon each encounter.” Rimbaud, who operates under the name Scanner, said that he’s long had issues with keeping music static on tape: “I’ve never considered a career of becoming a kind of electronic jukebox, playing back tunes that people might be familiar with from my recordings.”

His entry into Rijeka’s Music for Airports competition is called “Water Drops.” It’s a six-hour-long generative piece that consists of percussive, melodic instruments, all tuned to a musical scale that comes from the Istrian peninsula where the city is located. “It’s able to present an intelligent and sensitive environment with functional and aesthetic characteristics,” said Rimbaud. “Generative music continues my fascination with the unfinished, the changing, the new.”

Another competition entrant, Swedish musician and producer HÃ¥kan Lidbo, also took inspiration from the Istrian scale but prefers to use interactivity, rather than algorithms, to generate music. “It’s often difficult to hear the algorithm and then the magic gets lost somehow,” he said. “But interactive music, controlled by the audience or just unaware people passing by–I find very interesting.”

Lidbo’s is working his piece with several other artists–including Matt Black from Coldcut, sound artist Jack James, and local musicians from Croatia. It consists of a number of discrete pieces of music, played through many speakers spread over a large area of the airport, and controlled by the movements of travelers passing by. “When composed music and sounds are heard from everywhere, it’s quite different from when you normally listen to a recording,” he said. “Suddenly these artificial sounds get the same properties as natural sounds, like you’re in a forest.”

Both Lidbo and Rimbaud’s pieces will be installed in the airport once complete, alongside a third piece from renowned Croatian composer and keyboardist Aleksandar ValenÄić. “We didn’t expect such a response,” said Magas. “We got 104 registrations and 32 submitted finished works.” Of those works, eight were shortlisted and then the three winners above were chosen by a blind judging panel at the University of Rijeka. Each winning project will receive €5,000 [or about $5,405] to cover costs, and should be unveiled in summer 2016.

It’s not just airports where robots are writing music. A London-based startup called Jukedeck is pioneering the business of generative, ambient soundtracks for videos. Or it’s enslaved an AI and is forcing it to write endless jingles. Interpret how you like.

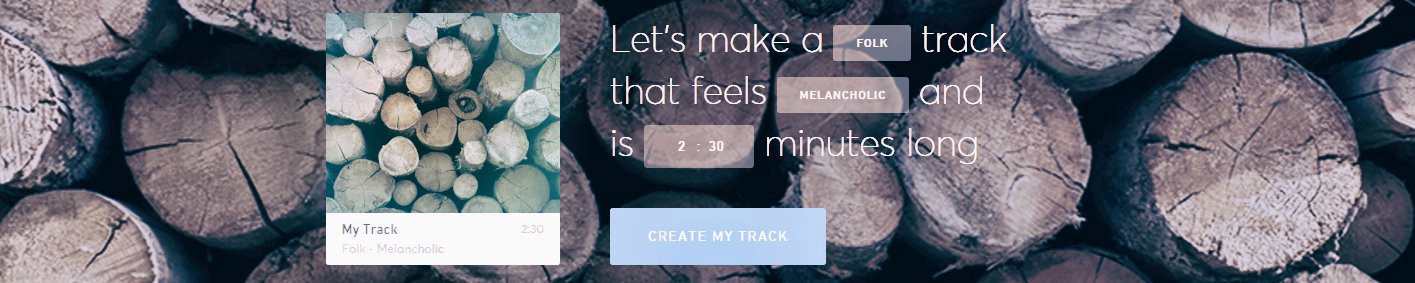

But seriously, you can try it yourself. Hit “Create Track,” then pick a genre, mood, and duration. I like making little five-second mini compositions that all sound a little like Eno’s “The Microsoft Sound” from Windows 95. You can also select instruments and a tempo, and in a few seconds you’ll have a song you can use to soundtrack whatever you want.*

The service has been in private beta for some time while working with Google and London’s Natural History Museum on music to soundtrack their videos. Now it’s launched publicly, and you can get five songs per month free before paying $7 a track. “We’re in the age of personal creation. This is the time for it,” co-founder Ed Rex told TechCrunch. “Music production is limited to a small subset of people. But we’re giving everyone in the world their own composer.”

Jukedeck and DeepBeat (which algorithmically writes rhymes for rappers) are extremely capable musicians in their own right, their flaws more than compensated for by their benefits over fleshy humans. Can a professional jingle-writer do a better job than Jukedeck? Almost certainly–but it’ll cost you, and Jukedeck gives you five passable jingles a month for free.

“For me, what will always remain is the voice of the individual,” said Rimbaud, explaining why he’s not worried about the threat of robotic songwriters. “No matter what the technology offers, the voice still needs to be present. Why do you like the work of a particular musician? Or writer? Or poet? Or film director? It’s because their voice in some way speaks to you directly, touches you, makes you laugh, or cry.

“All art and culture continues to alter and develop with the pace of technologies. It’s impossible to ignore that,” he continued. “For me, what remains the same is an integral understanding of feelings, experience, memory, stories, that use these tools to create works that can now commonly be experienced far beyond any historical confines of space, building, and location. Works enhance, enrich, teach, and ultimately move us to think, rethink, argue, debate, and remember. Technology does not stop that in any way.”

Libdo, too, is sanguine in the face of the robotic onslaught. “In the past 10″”15 years music has changed from a piece of plastic bought in a record store to something like fresh water or democracy–a human right,” he said. “I’m convinced that music will change even more radically in the forthcoming years. I think that we might even reveal the great mystery of music, how it affects us, how we can use it to change ourselves, where it’s coming from, and how it made us who we are.”

* I would really like someone to hack together a loudspeaker that plays a newly composed, five-second piece of music from Jukedeck whenever anyone enters a room. A personal theme song for everyone. How awesome would that be?

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Fast Forward section, which examines the relationship between music and innovation. Click the logo to read more.