The news is supposed to tell us about the world. But while news, information, and truth are closely related, they are not synonymous. Truth is on shakier ground than ever before, in part because of changes in how we receive our information.

In the last decade, we’ve seen the institutions that once held a monopoly on our attention–film, TV, print–challenged by the internet and social media for that attention. The infrastructure of social media, in particular, has put propaganda on par with verifiable work by trained journalists, with social media site owners too slow to respond to help fix the problem.

There may be others at fault, though. By uncritically embedding itself into this new system, did the media actually usher in the era of fake news?

Twisting the truth for the sake of a juicy headline is a time-honored tradition. “William Randolph Hearst [the publisher responsible for the biggest newspaper chain in the late 19th century] was known for vilifying people,” explains Bill Kovarik, a media historian at Radford University. “One of his reporters found out that somebody who was arrested on cocaine charges in Chicago in 1904 signed her name as Annie Oakley. So Hearst claimed that Annie Oakley was a cocaine addict. She sued for libel, but she couldn’t catch up. Hearst newspapers faked this news in order to hold somebody up and destroy them.” Sensationalism sells.

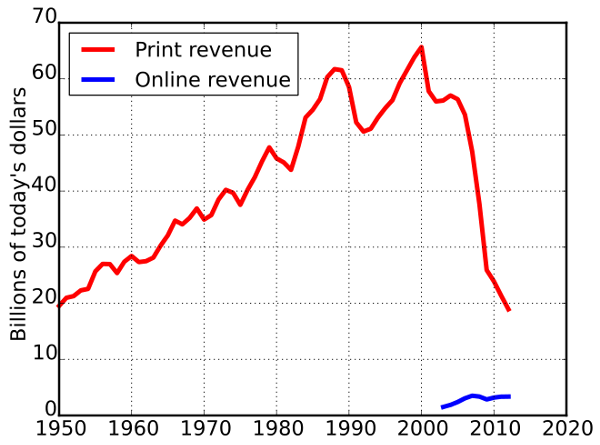

The difference today, Kovarik points out, is that the business model for the news industry–which began with the “penny press” in the 19th century–is failing. Penny press newspapers were cheap tabloids, heavily dependent on advertising as their main source of revenue. This funding model has prevailed well into the modern day, from tabloids to broadsheets, but has been in crisis for more than a decade.

“Mass advertising does not pay the freight anymore,” says Kovarik. “The penny press model made the press independent of political parties–so with the failure of [that] model, we’re falling back on partisanship. Controversy always sells, but that’s accelerating, too, because people are so desperate for money that they’re chasing these low-rent controversies rather than trying to present high-tone news “¦ This weakened atmosphere, and weakened financial infrastructure for the traditional media, has allowed these sharks to come in from the sides and have a huge influence.”

Single-issue political websites first took advantage of this new attention economy. One example (though by no means one of the first) took place in July 2015, when lifenews.com published what would be the first in a series of videos attacking the reproductive health nonprofit Planned Parenthood.

The battle for reproductive rights is far from new. This year is the 44th since Roe v. Wade, the landmark Supreme Court decision ruling that to block a woman’s right to terminate a pregnancy in the first trimester violated her right to privacy. The ruling was far from unexpected. The Great Depression saw women seek backstreet abortions because they couldn’t afford to make their families bigger; in the years before the Roe v. Wade decision, groups of young women took it upon themselves to learn how to perform abortions themselves, founding organizations like the Jane Collective. Still, there have been fierce efforts to delegitimize the ruling ever since–including a campaign to excommunicate one of the judges involved in the decision from the Catholic Church.

What is different now about attacks on organizations like Planned Parenthood, though, is that anyone can spread falsehoods in the name of influencing the larger political debate–and sometimes just as easily as a large media organization.

The July 2015 video series included footage recorded secretly of a meeting between actors posing as staff from a fake biomedical research company looking to procure fetal tissue for scientific research and Planned Parenthood’s senior director of medical services, Deborah Nucatola. The video was obtained and released by the Center for Medical Progress (CMP), a group of self-styled “citizen journalists” with no training, helmed by anti-abortion activist David Daleiden.

The original video was two hours and 42 minutes long; but, because nobody other than a journalist, policymaker, or the most dedicated anti-abortion activist would sit through all that footage, the CMP also released a heavily edited, eight-minute version. The aim was to assume criminality on the part of Planned Parenthood, accusing Nucatola of administering illegal partial-birth abortions. It also suggested that the organization was selling the fetal tissue that had been donated by its patients for profit.

Neither allegation was true–a fact confirmed by the longer version of the video. Despite this, outrage ensued among America’s anti-choice internet, on sites like The Weekly Standard and The Federalist. While these reports did not appear in the mainstream media, they were not on fake news sites either. Instead they were hyper-partisan websites, presenting facts with a little bit of spin. Journalists elsewhere attempted to fact-check the video. Some pointed out that the practice wasn’t illegal; FactCheck.org spoke to experts who confirmed that Planned Parenthood could in no way be profiting from the money it legally received to cover “reasonable” costs.

Hyper-partisan outlets dismissed these findings as partisan cover-ups. Were they “selling” or “donating”? Was it “dead babies” or “fetal tissue”?

The facts were damned, and the narrative was set. The point of the video release was to provoke visceral disgust at the practices of abortion providers among the general public.This hunt for wrongdoing was about ideological difference rather than facts, and portions of the public were led to believe that Planned Parenthood was actually running gruesome death factories.

The mainstream media and the CMP were the same in the eyes of those who matter: the public. Where did this equivalence come from?

A few years ago, the hot topic was not fake news, but clickbait. Founded in 2012, Upworthy quickly become one of the web’s fastest-growing sites, gaining nearly nine million unique visitors in its first six months. Initially funded by investors, the website didn’t have to doggedly chase advertising revenue. Instead, it had space to experiment and collect data.

Upworthy focused on promoting feel-good, issues-based, non-partisan political content with a liberal slant. It purposefully didn’t draw attention to angry and challenging campaign material–instead, the site gently took readers by the hand and went about revealing the world’s injustices by pointing the internet’s eyes at video clips with huge potential to go viral. Its headlines were written using the infamous “curiosity gap” to get readers to click on topics ranging from sex trafficking (“Who Doesn’t Like to Watch Half-Naked Girls Dancing? These Guys, After They See Why It’s Happening“), to the benefits of immigration (“Next Time Someone Tells You That Immigrants Are Destroying Our Country, Show Them This“), to income inequality (“9 out of 10 Americans Are Completely Wrong About This Mind-Blowing Fact“).

The formula for success involved what Upworthy called “emotional data,” or figuring out what makes people care about a story. In 2014, The Guardian reported that it would test 25 different headlines for each of its articles, collecting information on what makes readers click, and how to make things go viral. At the same time, Upworthy’s formulaic content drew criticism from its media peers, and even saw a parody headline generator created in its honor. But there was no doubt about it–the formula was successful, and it thrived within the relatively new framework of general news and information consumption via social media. Upworthy was perfect for an internet where Facebook and Twitter had become default homepages.

Mainstream media outlets, driven by a decline in print sales and a hunger for clicks and ad revenue, ran to catch up–not necessarily by exploiting the curiosity gap, but instead by writing attention-grabbing headlines. A Facebook algorithm change in 2013 intensified the need for catchy titles to draw readers in. “For publishers trying to grab more traffic from Facebook, the path became clear,” wrote Robinson Meyer in The Atlantic. “Borrow, adapt, and employ the Upworthy-style post haste.”

And many mainstream newspapers did: “Released From the Hospital, a Rabbi Assumes He’s Okay. That’s When Things Take a Turn” is a 2013 first-person feature in The Washington Post, for example. Upworthy’s time in the spotlight has been and gone, but it remains a key example in how publishers changed established standards in the pursuit of hits.

Many wondered, as all of this was happening, if chasing traffic this way was sustainable. The answer, as we soon learned, was no.

The consequences of mainstreaming the chase for viral traffic has been the fake news crisis, indistinguishable on first glance from the content running on legitimate outlets. Fake news creators lift articles wholesale from hyper-partisan political websites, adding sensationalist titles. And when they aren’t doing that, they write headlines that copy the style of sites like The Federalist and Upworthy, with one crucial difference: The stories aren’t rooted in truth.

Fake news websites like ccn.com.de publish stories like: “President Obama Declares September National Muslim Appreciation Month,” for example, or “Twitter Deletes Donald Trump’s Twitter Account: “‘We Will Not Tolerate Racism & Hate.'” In a sophisticated move for a fake news site, the date on the ccn.com.de articles can change depending on what day a reader clicks on the link, keeping a fake story looking timely and urgent. Another fake news website, abcnews.com.co, started a rumor that some of the people turning up to protest Donald Trump’s campaign rallies were only there because they had been paid to do so. This was the stuff of shady, unverifiable internet forums, draped in a news banner and presented to the public as truth–because it looked just like true content elsewhere on the web.

A Guardian investigation in mid-2016 revealed that 150 political fake news websites had been set up in Macedonia, a landlocked country in southeastern Europe. A Buzzfeed investigation, published later that year, revealed that many of the websites were in the business of writing fake, conservative-leaning news geared toward American Facebook users. Buzzfeed reported that many of the people running these websites were young adults; some were even teenagers, earning sums ranging from pocket money to a full-time livelihood from the ad revenue their websites brought in. Viral fake news is lucrative. It follows the viral blueprint of tapping into emotional data, with an almost intuitive understanding of what hits audience in the guts, and what can make people click and read.

“People in America prefer to read news about Trump,” one of the teenage fake news creators told Buzzfeed. Much of the content thereby involved an exploitation of the worst of the political psyche, including stoking up existing discrimination and prejudice against Muslims. Once emotional data had set the precedent for staggering emotional highs, it was followed by staggering lows–provoking not hope and admiration, but anger and fear.

The ongoing fake news epidemic also exposes the delicate line between hyper-partisan reporting and creating total fiction. The Planned Parenthood sting certainly wouldn’t have been so successful if the news cycle hadn’t already come to rely on the art of twisting the truth–or if social media hadn’t demonstrated its preference for hyperbole.

All of this has prompted seismic shifts in the political landscape. Whether it’s alternative facts or outright lies, the situation seems to be getting worse. The question is: What can we do about it?

Prosecution might seem harsh, but Kovarik is convinced that fake news creators are dealing in fraudulent activities: “If they’re in the U.S., they should probably be prosecuted for wire fraud if they’re making money. If they’re in Macedonia, I think international copyright laws, takedown orders, things like that could be put into effect.”

Kovarik cites the fourth stage of influential journalist and media critic Walter Lippmann’s theory of evolution of the press–organized intelligence. “I call it media for the people,” he says. “The power of the media needs to be shared with a lot of people at this point. Journalists need to come out of their cloisters and share that power with everybody.”

One potential, practical solution comes from a transatlantic group of researchers at the University of Cambridge. Led by Sander van der Linden, a social psychologist, the group conducted a study looking at how members of the public understand the facts and myths about climate change, concluding that it’s possible to “vaccinate” people against misinformation by using preemptive warnings.

“We told people before they were exposed to the information that there’s politically motivated actors, people with agendas that use misleading tactics to try and convince you of something,” van der Linden tells me.

“People are often on autopilot when browsing the news. We accept facts all the time from things that are unrelated to the message. Maybe the communicator is charming or convincing, or maybe it speaks to a sentiment I agree with, regardless of what the facts are. People are often willing to share and accept information without thinking about it. Those warning labels, that pre-exposure can make people more conscious, more vigilant “¦ The hope is that that will help slow the transmission of fake news.”

Sometimes the truth is contentious. But when fact is blurred with opinion, whose responsibility is it to set the demarcation lines? Facebook has now committed to flagging fake news stories that appear on the site in both the United States and Germany, with a warning label informing users that the information is contested. The company plans to roll the feature out to other countries in due course. For those working in news, this must have prompted a sigh of relief. Catching up with the new structure rather than setting it has been a recipe for disaster–fueled by Facebook repeatedly dodging the label (and thus responsibility) of a media organization.

We are also being told by opportunistic political leaders that the truth cannot be trusted–and in doing this, they are further spreading confusion and fear. Self-directed study is no longer an antidote to these campaigns of misinformation. Information is abundant and easily accessible, but not all of it is accurate. Over the last few years we have watched the intensification of what happens when the truth becomes partisan. Even third-party fact-checkers are proving futile. The news that a Swedish fact-checking group on Facebook was in fact doing the opposite by spreading propaganda is no longer the shocking stuff of dystopian fiction, but instead simply unsurprising in this new climate. Now, more than ever, the responsibility lies with readers to be critical of the media they engage with.

Sander van der Linden is well aware that his inoculation method could be used by political actors for malignant ends, but he tries to look on the bright side. “Just as science has a slow but sure way of filtering out incorrect facts, I think it’s the same with institutions,” he says. “The optimist in me says that it’s better to try something than to do nothing.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Together in Public section, on the way new technologies are changing how we interact with each other in physical and digital spaces. Click the logo to read more.