As part of our Afrofuturism coverage, we’re featuring interviews with makers, artists, and thinkers from around the world. Afrofuturism is not just an aesthetic–it’s just as much a framework for activism and imagining new technologies. We’re interested in how the movement can make a practical difference in the lives of those from whom the thought culture draws.

Founder and co-conspirator of Quirky Black Girls, Moya Bailey is a graduate of the Emory University Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies department. Much of her work focuses on issues at the intersection of race, gender, and medicine. She now serves as the digital alchemist for the Octavia E. Butler Legacy Network and is a core member of #transformDH, a movement aiming to increase diversity within the digital humanities.

Florence Okoye: OK so let’s start by introducing you to our readers”¦

Moya Bailey: I am from the South and my southern identity is a huge part of who I am. I work in women’s, gender, and sexuality studies and digital humanities. Mostly, I see my work as trying to help foster people’s thinking in expansive ways about the state of our world.

FO: It’s interesting how you initially studied to become a physician but have now become a digital activist and intersectional theorist. That’s quite a shift in some ways. What was the catalyst?

MB: Although I am really goal-oriented, I also feel pulled in particular directions. Women’s studies completely captured my imagination in college and I felt the urge to pursue it.

FO: What’s your biggest motivation to work on the kind of projects you do?

MB: I think by teaching young people that the world isn’t as fixed as it appears, you can open them up to new possible futures. Most of my projects are connected to imagining different ways of negotiating the structures we imagine as immovable. Whether its dismantling the ivory tower or celebrating the dystopian futures of Octavia Butler, I endeavor to remind people that another world is possible.

FO: That’s very much a theme in Butler’s work where there’s a kind of pessimistic optimism. The reminder that there is another way of being, but there’s never going to be an ultimate utopia. Were you interested in science fiction growing up?

MB: I have always been interested in science fiction. I loved horror and thrillers as a kid as well. I even wrote my own horror stories in junior high school. I also grew up in the 80s where children had access to weird sci-fi and fantasy stories like The Dark Crystal, The Goonies, Labyrinth, The NeverEnding Story, Flight of the Navigator, The Secret of NIMH, and Howard the Duck. I watched all of these movies and was reading all kinds of science fiction and fantasy. But in college, I went to the Yari Yari Pamberi Conference in New York in 2004 and Octavia Butler was there. I hadn’t read her yet but there was such a large gathering, a room filled to capacity to hear her speak. When she started talking I was blown away by her voice and her presence. I thought, I need to know her and her work. I devoured everything and became a huge fan. Her work captured me because even though there were fantastic elements, it seems all too real.

FO: Do you think that genre fiction can help inspire more active involvement in technology?

MB: We’ve seen a bunch of the technology from Star Trek developed into real technology we use. I think that is exciting. Whoopi Goldberg and black women astronauts often cite Nichelle Nichols’s portrayal of Uhura on Star Trek as the inspiration that led them to their careers. Making images accessible gives people the opportunity to see themselves doing a number of things that might have previously seemed impossible.

FO: And that’s very much the raison d’être of Afrofuturism–that in order to envision new futures, we need to see ourselves in depictions of the future. When did you first hear about Afrofuturism?

MB: I first heard about Afrofuturism as an undergraduate. I was struck by how it moved through all kinds of creative genres including music, fiction, and fashion, among others. I love seeing it in all its various forms.

FO: And how relevant do you think Afrofuturism is for the black community, especially in the political sense? There are so many issues that effect the global black community, stemming from racism, colonialism, and white supremacy.

MB: I think structural oppression has limited the radical imaginations of subjugated peoples around the world, including black people. Some black people with a little bit of power seem to believe that if black folks conformed better to the existing power structures, were more respectable, we would be treated better. I think we have seen over and over that this is wishful and dangerous thinking. Afrofuturism helps open up possibilities for black life that extends beyond the limits of our current societies. Afrofuturism means that we can envision black people in a free future, one without oppression. If we can dream it, we are more likely to achieve it.

FO: Music is a massive part of Afrofuturism. I’m forever quoting Eshun’s concept of black music as “sonic fiction”–but often it seems futuristic visuals and production methods don’t always lead to futuristic messages. You coined the term misogynoir and have written about homophobic and anti-women lyrics in contemporary hip-hop. Do you think things are improving?

MB: Not really. I think there’s still a [negative] way of talking about black women that is somehow compelling. In many ways it shows that our liberatory imagination just isn’t going far enough. Think of the respectability politics in “Classic Man.”

FO: Yeah! I mean I love vintage styling and classic clothing, but for me there’s meant to be something ironic about showing clothes from an era I would have been spat upon in the street.

MB: Right. Where is the irony? Black music still needs to discover opportunities to experiment with content, to create the new world we need.

FO: Who are the artists you would suggest as a counter?

MB: Erykah Badu, Missy Elliott, Sango “¦

FO: Moving more toward the literary end, Octavia Butler is a huge influence in Afrofuturism, particularly the emphasis on a more intersectional–queer-friendly, woman-friendly, class-conscious, etc.–Afrofuturism. What do you take from her work?

MB: Butler tells truth in fiction that would be too hard to tell in another medium. I am blown away by the economy of her writing, which is coupled with such deep and profound truth about the human condition. Even though her work is science fiction, it speaks so well to the problems with humanity and what might be required to shift our way of being.

FO: Now for the tough one–what’s your favorite book by her?

MB: That is a hard question, much like being asked who is your favorite child. I think one of my favorites is Fledgling because the model of relationships and family seems so ideal to me. I also really like the Parables because they describe a world not unlike our own, not that far off, and what will be required of us if we hope to survive. Also the gender of the Oankali, specifically the Ooloi is so inspiring!

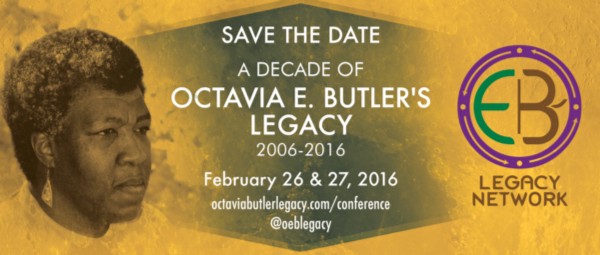

FO: You’re also a member of the Octavia E. Butler Legacy Network. Could you tell us about that?

MB: It happened rather organically. Ayana was doing this work around preserving and growing folks’ knowledge about the impact of Octavia Butler’s writing. We connected electronically and the rest is history.

FO: And now you have a conference. How is that shaping up?

MB: We wanted to acknowledge the 10 years since Octavia Butler passed in a big way. There are so many people who continue to be touched by her work, and we wanted to create an opportunity for folks to gather in celebration of all that she has meant and continues to mean to us. This gathering has changed shape, much like characters in Butler’s works, but the core remains the same. It is our desire to bring people together who appreciate Butler’s legacy and want to do work that is inspired by her life and writing. It is an Afrofuturist love letter incarnate with music, food, and fun all designed to celebrate and call forth the energy of the world we want.

FO: And there’s a crowdfunder also underway to support the conference.

Who are your recommended black female writers in sci-fi and fantasy working today?

MB: Nalo Hopkinson, Rasheedah Phillips, Andrea Hairston, and so many more.

FO: You created the term “digital alchemy” to describe how “everyday digital media is transformed into valuable social justice media magic,” which is certainly something I’ve seen grow on social networks like the much derided Tumblr. As a digital alchemist yourself, who also works in academic digital humanities, what do you see as your primary role?

MB: Digital humanities is both the use of digital tools to aid in the answering of humanities questions, and asking humanities questions of digital tools. I often use the example of Lauren Klein‘s work developing a coding script to scour the massive Thomas Jefferson digital archive to understand the significance of James Hemmings, Sally Hemming’s brother and Jefferson’s chef. It would have been nearly impossible to go through the archive by hand. The script she created made the research possible. Other projects might be interested in how social media is impacting our world and interactions. I see my role as being someone who champions people seeing themselves as connected to digital humanities if they didn’t see themselves there before.

FO: Would you consider yourself more on the technical side of the spectrum?

MB: As a digital alchemist, I see myself reusing and appropriating digital technology in ways that extend beyond its initial use. I like that I and other marginalized folks are able to take tools that have traditionally had very specific purposes and use them in innovate ways.

FO: Now, I’m a sucker for hashtag movements and anything that pushes for opening up academia, making it more diverse, more accessible. I’ve become kind of obsessed with #transformDH. But what inspired #transformDH?

MB: It started with a group of people at the American Studies Association who noticed that a lot of DH content and the creators were white, cis, able-bodied, U.S., straight men. They wanted to highlight “transformative” DH projects that engaged with communities beyond this subset. In so doing the hashtag grew and more people started to connect around the idea that DH is uniquely poised to address diversity. #transformDH has grown a network of scholars working in DH intersectionally and has expanded who and what counts in DH, including people outside of academia who are doing intersectional digital humanities work.

FO: What do you think is in store for the future of tech and the digital humanities?

MB: I think that the question of access remains essential. The internet is vital but not everyone has equal access. The internet isn’t free, but it could be even less free if we don’t pay attention to the ways corporations are trying to monetize all aspects of the digital world.

FO: You know that’s so true. The web is ripe for exploitation and on top of linguistic segregation, limited accessibility for disabled users “¦ in many ways we’ve been way too complacent. The web really isn’t free, neither literally free nor free from the differentials of capitalism and social biases.

So between #transformDH, organizing the Octavia E. Butler conference, The Obsidian Project–actually, could you tell us a bit more about that and how it fits into your vision of digital alchemy?

MB: It started from my observations of colorism within the queer community. I wanted to create a way to address the different ways people get treated without fetishizing blackness. You get a lot of animalistic tropes associated with darkness but I wanted to get deeper into the humanness of people, showing their images along their own words

The digital space opens up opportunities for queer black people to meet each other and makes space for others as well–there’s a magic in the way we come together. In that sense it’s a healing access to the community, especially when every day you often have to split yourself and your various identities.

FO: It’s kind of exhausting to be honest. I’d love to know more about any other projects you’ve got on board.

MB: I’ve been talking with people about creating free accessible Afrofuturist curriculum for K””12 students to supplement or replace public school education. We need to start early to shape the future we want. Charter schools and Teach for America are not adequately serving our kids. They have been called glorified temp agencies for privileged young people post-college.

I am super excited to be dreaming up alternatives with others who think there can be other pathways for learning.

FO: And we’re equally excited to have you join us to talk about your amazing projects. Thank you!

You can support the work of the Octavia E. Butler Legacy by donating to its crowdfunder. Make sure to follow the organization on Twitter @OEBLegacy and keep spreading the word!

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our collection of conversations about Afrofuturism, curated and edited by Florence Okoye of Afrofutures UK. Click the logo to read more.