As a structural engineer, I’m involved in the design of infrastructure and buildings–everything from residential buildings to places of work, entertainment centers to roads, bridges, and transportation networks. These structures allow society to function, heavily influencing our day-to-day activities and our interactions with each other.

Afrofuturism has made me realize that although I may be one of very few black women in engineering, I can use the opportunity to create new urban landscapes. I can shape the black narrative by physically influencing the ways in which our cities are built to reflect and encourage increased diversity.

Rather than being generalized by the past, we can create a new story–one that focuses on innovation. It’s about changing our black experience and creating a new history, one filled with phenomenal visual and physical designs.

And, to me, it also means being myself, unapologetically, and embracing all the different aspects of who I am: a young, black, ambitious, female engineer.

The more I understand Afrofuturism and relate it to my life, I see that it’s about sharing, celebrating, and presenting your talent with the world. Afrofuturism impacts my working philosophy, making me more intentional about my actions and prompting me to think about my part in creating our future.

I’m now more aware and conscious about what I allow to influence my life. I have learned that there are many different expectations and narratives put on black people–labels that we feel the need to fulfill. I’m now better able to look at things differently–things in movies, music, TV, and on social media. The Afrofuturism movement encourages me to think about myself not just as a designer, but as a designer of a future I want to live in.

Technology greatly affects how the black experience is presented to the world. Afrofuturists are using it to both highlight the under-representation of black people in tech and create a new vision of what the future will be– all the while inspiring young black people to be part of it. Being an Afrofuturist means countering the stereotypical labels used for black people and taking control of our story by adding new dimensions.

In the same way we use technology to transform our social environments, we can also use it to change our physical ones. By designing structures and landscapes I have an opportunity to be part of the future through structures that will exist for decades, or even hundreds of years beyond my lifetime.

What does an Afrofuturist city look like?

The needs of cities are rapidly changing as their populations grow–and the rise of “smart cities” is one response. Smart cities integrate digital technologies, intelligent design, and communication systems into every aspect of infrastructure to address issues such as energy use, mobility, economic growth, and security.

This act of balancing social, economic, and environmental demands lies at the core of sustainable design and engineering. Our predicament as structural engineers is that, although there are many economic constraints, the most critical factors that affect our future are environmental. We need to build sustainably by designing to help society reduce waste and conserve energy, showing people that they are part of the solution in creating a more sustainable future.

One way to build sustainable structures is to use timber. Advances in design mean we’re able to use renewable resources to build much more complex and sophisticated structures than we once could. And, although timber is energy-efficient and renewable, we must take care to ensure that it comes from a reputable source to guarantee its regeneration.

Here’s one example of what might be sustainable Afrofuturist design–the Makoko Floating School in Lagos, designed by Nigerian architect Kunlé Adeyemi of firm NLÉ:

Afrofuturist engineers can look to the African continent for all kinds of inspiration for sustainable urban construction like this, from the contemporary to the historical.

In addition to building sustainable structures, we can conserve energy and reduce waste by managing energy use within cities. In an ideal smart city, systems that provide water and electricity are monitored and adjusted in response to a change in demand. Electricity is renewable, coming from sources like solar panels, and conserved with the use of energy-absorbing thermal materials and ample use of natural light.

Local businesses will also be supported by design. That means making sure infrastructure is flexible enough to cope with an economy that mixes online and physical services, and which accepts that people are going to demand choices for how they shop and travel. Going outside should be enjoyable–the quality of transport links, the built environment (like parks and boulevards), and public services must be of a high quality.

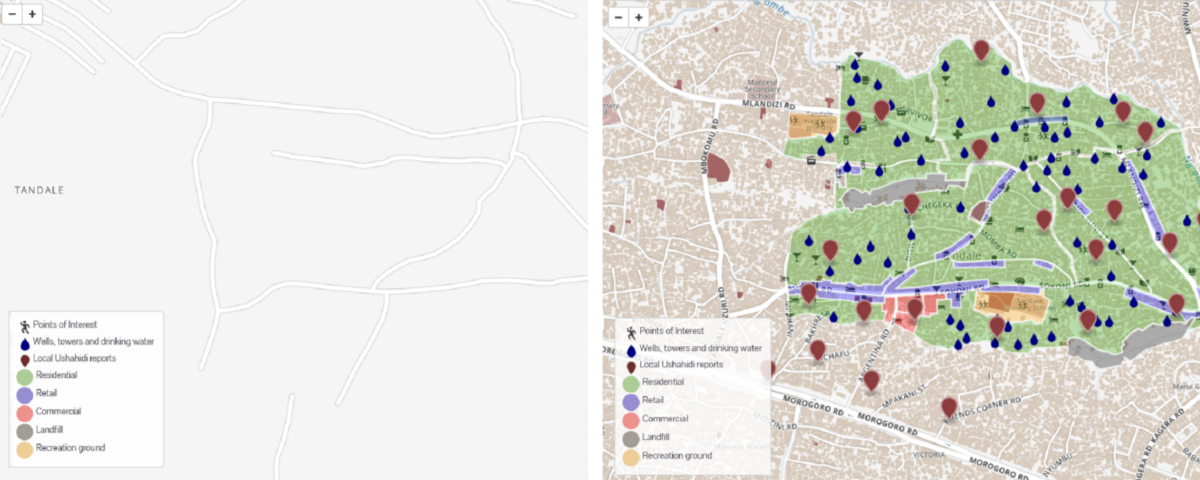

One major area of innovation that we’ve already seen across Africa is social and participatory mapping, where new communities take it upon themselves to map their neighborhoods and businesses.

Maps are vital to cities–without them, citizens have severely limited access to public services like running water or trash pickup. One example of participatory mapping that’s worked successfully is the one in Tandale in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania:

These maps have led to a rapid improvement in the services that residents can access–and all it took was a mobile app (using software from OpenStreetMap and Ushahidi). People can record bits of their district and highlight points of interest, including things that need improvement or fixing. Best of all, it means that everyone gets an address.

We call this the “data-ification” of the city; we see it as a shortcut to achieving the kind of smart cities that current developed nations have–without the long-drawn infrastructure. (You can see a similar thing happening in telecommunications, where many African nations are skipping the step of laying physical phone cables in favor of mobile networks.) It benefits future African cities by integrating the lessons that developed cities have learned while straining under new demands–less developed cities can easily incorporate the resulting technology into their designs now. Meanwhile, engineers like myself ask: Is the city efficient enough to cope with the current needs of the society living within it? And can we use the data we have to predict the changes that will be necessary for the future?

This will also influence the design of future structures, and the future success of urbanization will likely depend on this data. This type of design process creates a city that’s better customized for the people and their needs and will hopefully improve social integration and economic growth.

There’s a lack of diversity in STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), and there are various social reasons for it. One major barrier for young black people is that they don’t see anyone who looks like them in those industries–and who wants a career in a field that makes you feel unpleasantly exceptional?

For me, the celebration of successful black women is crucial to inspiring the next, bigger generation. You can see this theme on social media–for example, the Twitter hashtag #blackgirlmagic is about celebrating amazing black women in various industries: sports, entertainment, STEM, and more.

I’m trying to inspire other young black people by being part of Yakhani, a collective for women of color in Manchester, U.K. I organize events which aim to empower, celebrate, and support young women who are in education, beginning their careers or building their own paths through entrepreneurship. Yakhani is about creating a platform for black women to present their own narratives.

The statistics show that black women still only make up a small percentage of those who study STEM subjects. Being a part of a collective like Yakhani is as vital to me as my engineering work, because it emphasizes empowering black women to follow different career paths other than the status quo.

And that goes back to my understanding of Afrofuturism–that black people should take part in creating our future. Encouraging black people to create new structures is just as crucial for changing that future as is changing the technology, visual art, music, fashion, movies, and other representative media that we see every day.

Further reading

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our collection of conversations about Afrofuturism, curated and edited by Florence Okoye of Afrofutures UK. Click the logo to read more.