As part of our Afrofuturism coverage, we’re featuring interviews with makers, artists, and thinkers from around the world. Afrofuturism is not just an aesthetic–it’s just as much a framework for activism and imagining new technologies. We’re interested in how the movement can make a practical difference in the lives of those from whom the thought culture draws.

Throughout Africa, the contemporary art scene is filled to bursting with exciting new talent, both from within the African continent and the black diaspora. Many of these young artists are using their work to engage in political and social discussions. One such artist is Tabita Rezaire, whose works tackle race, gender, decolonization and digital diasporic politics.

Florence Okoye: Could you briefly introduce yourself to our readers, in your own words?

Tabita Rezaire: Tabita, a.k.a. hybrid femme emotional-warrior-healer preaching for earth-mind-body-tech-spirit communion! I’m Guyanese/Danish, raised French, now living in South Africa trying to sort myself out and make sense of the worlds I’m in. I see myself as a health practitioner–all my work is about developing emancipatory tools to nurture our health: not just physical, but emotional, spiritual, mental, historical, sexual, political, and technological as well.

FO: How did you start out as an artist?

TR: I actually wanted to be a fashion designer, then a filmmaker. I guess I embraced what turned me on: dressing up and cinema. Though I got brainwashed on the way and studied economics. How to become an exploitative capitalist believer? No thanks! University can be such an oppressive place, the whole hierarchic “learning” situation where you’re supposed to shut up and just consume and repeat the whitewashed nonsense you’re told as fact. History is so fictional.

FO: What drove you to using digital media?

TR: I guess my work comes as a response to this, using the screen as a tool for social and historical resistance. My work was always centered on body-screen politics but I used to be into analogue technologies. I would invite people to dress up and we would cover ourselves in glitter to play erotica-exotica fantasies, but I couldn’t afford to develop my films so I gave up and went digital.

FO: You’ve worked on a project called AfroCyber Resistance (watch it here), which sounds amazing. Could you tell us how that got started?

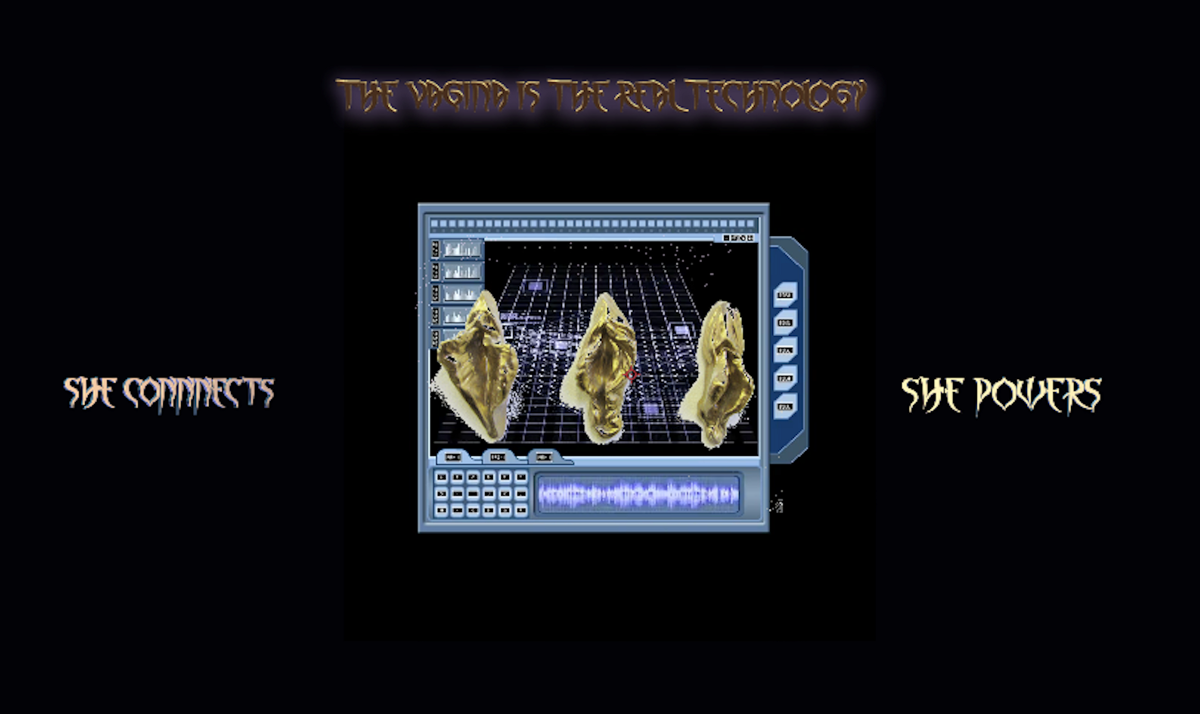

TR: I was looking at the politics of the internet on the African continent since I moved to Johannesburg. I realized how technology itself reproduces racism, sexism, homophobia and the exploitation and dehumanization of QTPOCs, allowing the West to shape and control behaviors worldwide. I was invited to present my work at Fak’ugesi Digital Africa Conference in 2014, so I made that video for it. I wanted to celebrate artists who were using the internet to confront stereotypic representations of African bodies and cultures. The discussion is always centered around the lack of access and the digital gap; excluding Africans and, more generally, black people from any conversations around technology. But we’ve been in the game!

It is still an area of research and practice, decolonizing the history and use of technology in the broadest sense, though I’m not sure about the prefix “Afro.” It’s also important for me to celebrate other healers/warriors doing important works and to create a network to support each other.

FO: I’ve been following your work for a couple of months now and it always strikes me that there’s something subversive but slightly parodic about the way you use visuals from pop culture and the late 90s net. It’s almost like you’re subverting the stereotypical tech aesthetic of a time when the net was less advanced, and alternative voices more underground.

TR: Well, that is the “global” aesthetic of internet art practices. It’s definitely ironic. I guess I’m trying to explore the politics behind this presumably global internet culture. What does it become when it’s consumed by people it was not meant for?

We then started chatting about one of Tabita’s works in particular, a video piece called “Peaceful Warrior.”

“The need for self-care is real. In “‘Peaceful Warrior’ I’m being over-serious, trying to share strategies of survival,” she told me.

Watching Tabita’s videos is the visual equivalent of my intersectional feminist awakening. Like looking back at all the TV and magazines I once consumed with a kind of harrowed nostalgia, the bright covers no longer quite so innocent with a headful of bell hooks and Judith Butler.

“It’s using mainstream media to tell uncomfortable truths,” Tabita said, nodding as I mentioned the intriguing dichotomy between her visuals and the message of radical self-empowerment.

That contradiction is almost fundamental to Tabita’s work. During our conversation we talked about embracing contradictions–how what we experience in our everyday lives can be potential for healing and poison simultaneously, like food, medication, information or relationships”¦ that’s why she likes the symbol of the snake, a symbol nth feared and venerated, used for curses, healing or divine intoxication. As we discussed her work further, it became clear that it very much draws from her practice of socio-cultural political exploration. Tabita’s work is based on months of reading, self-examination unlearning and constant dialogue.

“Peaceful Warrior is about building a spiritual communityf or a more efficient struggle.

“It’s all based on my own experience and my need for self care “¦ I’m sharing my own healing journey.” A journey through time and space, I replied.

The video’s audio is a mystic chord by her friend, the musician Hlasko, also member of the band Kaang. He says, “the piece of music is a map of tabita’s room, which is a strange and comfortable space, where a collection of lamps creates a microcosmic dimension. The order of those lamps is what inspired the voyaging structure of the song.”

Similarly, her practice of decolonization absorbs methods from across the African continent. Healing frequencies and Kemetic yoga are combined to exemplify Tabita’s practical but intersectional approach to decolonization. The healing is in the art, I can’t help but think to myself.

FO: So what made you move to South Africa?

TR: I moved for love. It’s been a very inspiring place to be in and grow, but very intense. The way my identities play here takes on a different meaning, and the feeling of privilege (due to colorism and classism) is overwhelming because of the social, hierarchical legacy of apartheid.

I sometimes feel like my position here is problematic, like I’m given so much exposure and some people expect me to speak for SA–no, let South Africans speak for themselves! There are similar experiences with diasporic struggles–it’s the other side of the same history–but I can only speak from my experiences. I’ve always felt misplaced and I guess I’ll be looking for home my whole life.

I often think about Fanon and Che Guevara and how they respectively dedicated their lives to the struggles of different countries. I do also think that the concept of nationalism is flawed; more solidarity over one’s own borders is necessary, especially as borders are a direct legacy of the colonial era, though it should not mean co-option.

FO: And the Johannesburg art scene?

TR: It’s amazing, I really feel like I found a family of babes to work, struggle, and cuddle with.

FO: Cuddly comrades in arms “¦ or art! What’s it like being a young black artist in South Africa right now?

TR: You need some professional hustling skills.

FO: What doesn’t change! In an age where the arts are strapped for funds, do you think about the government and its support for the arts? Do you think it does enough?

TR: Definitely not. It’s mostly the private sector or foreign organizations funding the art, so again it’s the West writing the continent’s cultural history as they get to select who gets funds for what. You know what would improve things? Paying artists! We just can’t afford to work for free; that global art exploitation has to stop!

FO: I hear you. Sometimes I think the proliferation of art on the internet makes it easy for people to forget that it involves real work and artists deserve fair pay, then I remember artists have been kind of downtrodden since time immemorial. Actually, on the note about technology impacting art–I notice there’s a lot of futuristic effects in your digital art. Were you interested in science fiction/fantasy/genre pop culture?

TR: I grew up watching Sailor Moon and Dragon Ball Z. That’s how far my sci-fi game goes.

FO: Aha! I was a Dragon Ball nut as a kid. It’s super ridiculous, but I just liked how it was so over the top. Anyway, the reason I ask is that there’s a lot of interest in Afrofuturism and how, in some ways, it’s a reaction against the under-appreciation of black involvement with sci-fi. What do you think about Afrofuturism?

TR: To be honest, I struggle sometimes with the “Afrofuturism obsession.” Afrofuturism is a product of 90s African-American cultural history. It’s an important cultural manifestation that addressed the identity alienation of Afro-diasporic subjectivity, asserting black bodies within a culture of technology and advancement that was denied to them. I think it was about healing their aspirational future to deal with the present, but it’s very much rooted in a specific context and geography. These days, as soon as a black person deals with technology it’s Afrofuturist. Don’t force it down our throats! Black people have developed scientific and spiritual technologies forever.

FO: I think for me, when looking at the global narrative (if there is one) that’s where I think the intersection of art and politics–which is a commonality between Afrofuturism proper and contemporary African art–lies.

TR: The appetite for it lies in the politics of possibilities. What could it be like? What are we doing to make it happen? How are we going to fight for it?

I think a lot of African and diasporan artists are trying to reconnect with their historical pride. Black people are inspirational, innovative, and magical–they have been forever. We just need to peel off the layers of shame.

FO: As part of the healing. I love how that’s something which permeates all your art and your projects. Like NTU, the health tech agency you are part of. How did that get started?

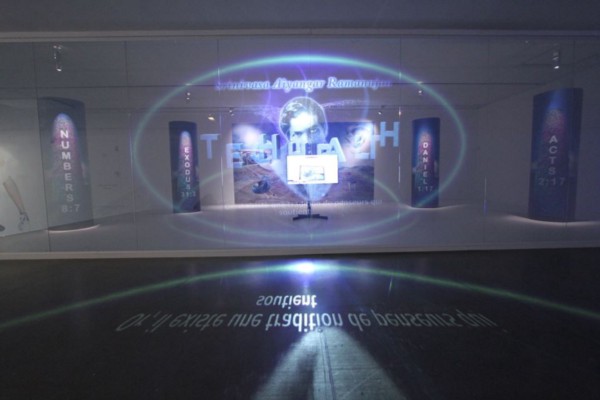

TR: NTU is a collaboration with Bogosi Sekhukhuni and Nolan Oswald Dennis started in 2015. We’re concerned with the spiritual futures of technology and seeks to provide decolonial therapies for the digital age.

So far, we’ve developed a network prototype for people of color on the deep web and recently collaborated with Maxwell Chikumbutso, a Zimbabwean inventor, on a video installation around the politics of faith and free energy. Our work is inspired by African spiritual philosophies and embraces the interdependency of organic, spiritual, and technological realms to restore energetic and technological imbalances. We’re now developing a cryptocurrency for a commissioned by Cuss Group for the Berlin Biennale.

FO: How do you see your work in light of resurgent, albeit more intersectional, black activism (e.g., Black Lives Matter in the United States and similar movements) around the world?

TR: We are siblings in struggles! There’re definitely similarities in diasporic experiences and concerns. It gives me so much strength to see this global network fighting for our dignity and trying to nurture solidarity. Our history will always be part of our identity, and as long as this history (and her/theirstory) will be traumatic and not acknowledged for its worth and wisdom, our identities will hurt. But the question we have to ask ourselves is who do we want those stories to be acknowledged by? Healing starts within our own communities first.

FO: What will you be up to in the next couple of months?

TR: Aww 2016, I’m coming for you! I’ll be showing work at MoCADA–Contemporary African Diasporan Arts–in Brooklyn next month, starting a series of video interviews of healer-warrior babes, and hopefully launching an online space soon. Otherwise I’m working on a solo show in Johannesburg and opening an art/pole dance/health space in my garage!

You can find more of Tabita Rezaire’s work on her website.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our collection of conversations about Afrofuturism, curated and edited by Florence Okoye of Afrofutures UK. Click the logo to read more.