For a few short years in the mid-1980s, when the pockets of New York’s broad-suited investors swilled with Reagan-era money, one item of clothing defined the luxurious moment above all others: the pouf dress.

Designed by Christian Lacroix, a couturier from Arles in the South of France, “le pouf,” as he referred to it, presented an explosion of material betwixt the waistband and the knee. This ball of fabric preposterously accentuated its wearer’s hips, giving a woman the silhouette of a tottering doll. The pouf was the must-have item in nouveau riche couture, filling ballrooms with what, at a glance, looked like a sea of brightly colored balloons. Then, in an instant, the pouf deflated.

Following the 1987 stock market crash, what was once seen as a shibboleth of status became a vulgar display of wealth. “The skirt’s flamboyant silhouette was suddenly deigned to be frivolous,” explained David Wolfe, creative director of The Doneger Group, the New York-based company that advises the fashion and retail industries on the ebb and flow of trends. “It crashed and burned overnight,” he said, the skirt to be immediately replaced by more austere cuts such as the pencil line.

Wolfe, who is balding with thin-rimmed, tortoiseshell glasses and a tidy gray beard, was one of fashion’s very first trend forecasters. Now in his mid-70s, it has long been his job to predict the next big thing; The New York Times has described him as “fashion’s most authoritative spokesperson.”

In what is often seen as an elite business, guided by the caprice of figureheads like Anna Wintour and big-name couture designers, for Wolfe the fate of the pouf skirt reveals an often-overlooked truth about the rip tides of what’s en vogue. The popular perception is that any given season, it’s the high fashion mavens that decide the newest styles–their clothing lifted from the runways, redesigned for the masses in more conventional cuts, and made popular by marketing campaigns played out on widescreen billboards and the miniature windows of trendsetting Instagram girls.

In fact, said Wolfe, trends are just as equally driven by a complex mesh of political, economical, social, and technological factors–everything from the state of war to the state of the economy. “Fashion is a response to how consumers react psychologically to every aspect, nuance, and factor of life,” he explained. “Everything that plays a part in creating the world we live in is reflected somehow in fashion trends.”

Understanding the science of fashion has, over the past 40 years, become big business. The scale of bets involved in designing, producing, and selling a new line of clothing has created a market for seers, people who are able to advise big business on what designs will prove popular in the near future, based on evidence rather than whim. David Wolfe was one of those first oracles.

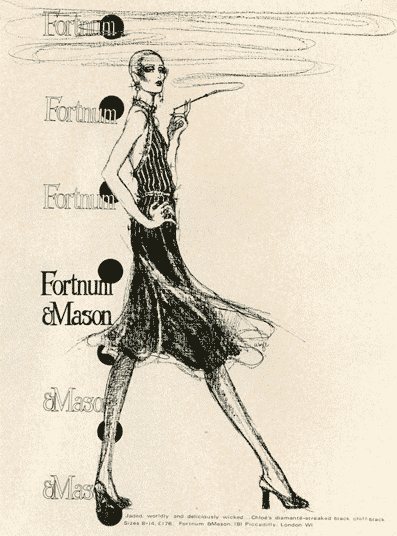

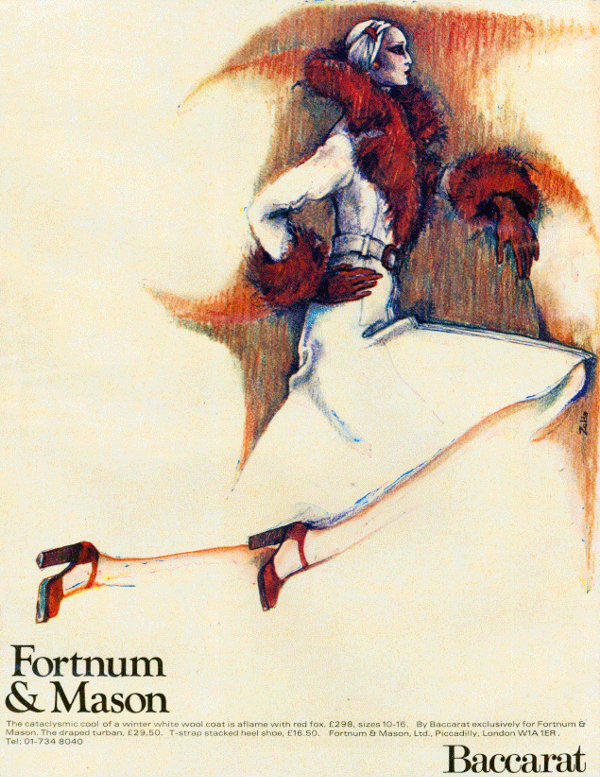

After working as an illustrator at London department store Fortnum & Mason in the 1960s, Wolfe used his talent for observation and artistic record to fill a void–founding one of the world’s first fashion forecasting services, Imaginative Minds International. His objective at the time was to feed privileged information about the latest collections shown on cloistered Paris runways to English and American designers.

Wolfe’s methods in those early days were rudimentary but determined; he would disguise himself to gain entry into French fashion shows and then sit in the back row, incognito, while making surreptitious sketches of the dresses drifting down the catwalks. He was, by then, already recognized as one of London’s leading fashion artists, his sketches published in Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Women’s Wear Daily, and The London Times. Wolfe’s insider work attracted a raft of high-profile clients, including Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren, and Versace. Through his insight, designers around the world were able to catch emerging trends and turn his pronouncements into realities as, en masse, they followed his advice.

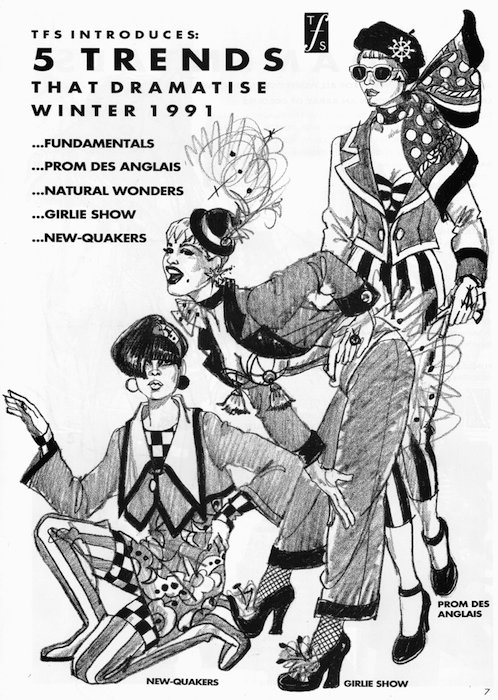

Wolfe’s instincts proved correct–especially in terms of recognizing a market for trend forecasters. After moving to New York in the early 1980s to set up the first dedicated fashion forecaster in the United States, TFS The Fashion Service, Wolfe joined The Doneger Group in 1990. In earlier years, consultants like Wolfe could take a punt on what they thought was going to become the next big thing in fashion and, if they were fortunate, see their predictions turn into reality. Those with a knack for soothsaying (or whose predictions were later backed by multimillion-dollar marketing campaigns to become self-fulfilling prophecies) reaped the rewards. Those whose predictions proved to be off-trend, meanwhile, were considered snake-oil salesmen. Luck, as well as observational aptitude, surely played its part.

Today, advice must be backed by quantifiable facts and information. As technology has increased the amount of data that is gathered and quickened the pace at which it disseminates, so have Wolfe’s methods of gaining insight into future trends been forced to evolve and adapt. “It’s much more business-driven today simply because it is now possible to access in-depth facts and figures,” he said. “Today, future seasons are forecasted by looking at the success and failure rates of existing merchandise and combining this with comprehensive sets of information about movements in culture, politics, economics, social media, technology, and entertainment.”

This is serious work–no more does the solitary forecaster arrive at a fashion retailer like Moses coming down from the mountain, clutching prophetic wisdom. Trend-forecasting teams are multi-role affairs, often consisting of a host of directors (a creative director, a color director, a fabric director, an art director) and a copywriter, each of whom are further supported by teams of assistants, researchers, and beleaguered interns. Together they look for trends on the runway and the street, while simultaneously monitoring the slow tides of societal change, and how they might have an effect on shifting design patterns.

“Trends are a reflection of the society that responds and buys into them, so it is vital to understand and project-forward the current zeitgeist,” Wolfe said. In one example, he believes that recent shifts in wealth between the young and old are reflected in high street fashion. Millennials are the first generation to be worse off than their parents and grandparents. As the wealth base shifts, and as people are living longer and staying healthier, baby boomers are, Wolfe said, regaining economic control of fashion. This shift has influenced color and style, favoring designs that are ageless, rather than tailored to any particular age group or demographic.

For the younger designers and Wolfe’s forecasting descendants, however, there’s no substitute for getting feet on the ground. Many believe the next hot item can seem less to do with current affairs than the minutiae of what’s being worn in key cities around the world. Rachel Mcculloch, a senior designer for Topshop Boutique who has designed clothes for Gap, Topshop, and Topman, is part of a group that tours key cities as on-the-ground spotters.

“Our team takes a very collaborative approach to trend direction,” she said. “We undertake enormous amounts of research, shopping all over the world in areas where fashion and style have exciting ideas such as Seoul, Tokyo, Los Angeles, and Stockholm.” Mcculloch also does her virtual homework, sifting through fashion blogs and Instagram accounts, while analyzing runway seasons for common themes and, as she puts it, “outstanding new concepts.”

“The real task is being able to assimilate all the information from all the different sources and ascertain common emerging threads and ideas,” she said. “We come together as a team and discuss the big ideas that we are all seeing, and decide on which ones to take forward. The process can be quite methodical and scientific but is mostly decided on gut feeling. We decide upon colors, cut, mood, and detail in this way, and then our management team creates a comprehensive and clear guideline from this for all team members to adhere, too.” For Mcculloch, data plays a role, but ultimately “gut instinct and intuition are the most important thing.”

Relying on intuition may be the most attractive approach for artists and designers, but for shareholders and managing directors, these nebulous qualities are cause for concern–the area where art and business have forever rubbed up against one another. In 2016, fact-based forecasting is the crucial way to position oneself as a trend forecaster. Doneger has, Wolfe said, access to a “wealth of in-depth information that allows trend analysts to make projections based on facts, rather than “‘gut instinct.'”

In this way, forecasting is shifting toward something you might call “nowcasting”–the ability to recognize, through vast collections of data, which emerging fashions might, with a little encouragement, become full-blown trends. Geoff Watts and Julia Fowler co-founded EDITED in London in 2009 in response to Fowler’s frustration that too often decision-making in fashion design was based on feeling rather than metrics. At the time her partner, Watts, whom Fowler met while racing cars in their native Perth, worked for a dairy company in an industry where every decision was based on evidence, not instinct.

“We’re helping the industry move out of the old “‘trend forecasting’ model, which you might at best call educated guesswork, by actually putting the market’s real product, pricing, and promotional data at its disposal in real time,” Fowler said. “You could say EDITED removes the uncertainty of “‘forecasting’ and replaces it with facts.”

EDITED’s clients, which include Topshop, eBay, and Ralph Lauren, have certainly benefited, in particular from the company’s advice on how to price individual items competitively at key moments in each season. In 2014, for example, ASOS–one of the company’s first customers–attributed a 37-percent revenue increase to EDITED’s data insights.

Those insights are drawn from a close examination of its clients’ competitors products. The EDITED team then claims to track key data such as price, discounting history, and the timings of seasonal pushes. “This helps them use data to understand the market and have the right product at the right price, at the right time. It’s less about looking into a crystal ball, making a guess, and hoping for the best, which until now has pretty much been the status quo,” Fowler said.

This work isn’t so much trendsetting as trend-monitoring. Using the company’s services, fashion buyers and merchandisers can size up the commercial state of trends in the market. If they see, for example, that the products associated with a trend are experiencing low rates of sell-through and replenishment paired with high rates of discounting, they know that a trend is on the downturn. That information can be immediately fed down to their clothing designers, potentially saving millions of dollars on a poor or tardy gamble.

Fowler argues that the tools are useful for spotting emerging trends, too. “We can see where items are selling out quickly at full price with low market saturation.” EDITED also provides “crucial pricing and promotional data,” to enable its clients to know when to push a certain item of clothing, and when to discount it at the optimum moment. Fowler describes the company as owning “the world’s biggest apparel data-warehouse.” Buy its services and you gain access to those stores of information, enabling you to track new product launches, price changes, and discounts, all the way down to the content and timing of a rival’s promotional emails.

“We can contextualize all that data and make it available to our clients in real time so that they can use it in their market analysis and make confident pricing, product, and timing decisions based on the true state of the market,” said Fowler. “Reliable data can even provide enough support to justify forgoing soft launches or long, drawn-out testing periods–meaning you can get the right product to the right consumer even faster.”

These tectonic shifts in trend forecasting have been driven by technology. “Right now data is at the forefront of a significant shift in how the industry does business,” she said. “Anyone who isn’t already using real-time global data in their planning and trading strategy is setting themselves up to be left behind.”

While newer fashion forecasting has brought data and efficiency to the market, it may have unforeseen side effects. There is a danger with the methodology that fashion, which is supposed to enable individual expression, will become homogeneous.

Indeed, it can already seem as though major retailers are conspiring when they launch eerily similar designs at the start of a season. Mcculloch denies such a possibility. “Companies sharing ideas to create a trend force on the high street would never happen,” she said. Rather, any synchronicity is a function of the shared data flowing into the design process.

“Companies are competing to get the newest ideas in first–but as the world becomes more global, more and more I find that we are all viewing the same information and research,” she said. “The cities I travel to are slowly beginning to offer very similar things to each other. The differences are becoming less pronounced. It feels inevitable that eventually we will all be offering the same things. The questions of who can be the quickest and most innovative with those designs has, rightly or wrongly, become the real competition.”

When clothing in every major retailer from London to Tokyo to Los Angeles begins to look the same, there may no longer be a place for the trend forecaster–especially as companies fully shift their faith from instinct to algorithm.

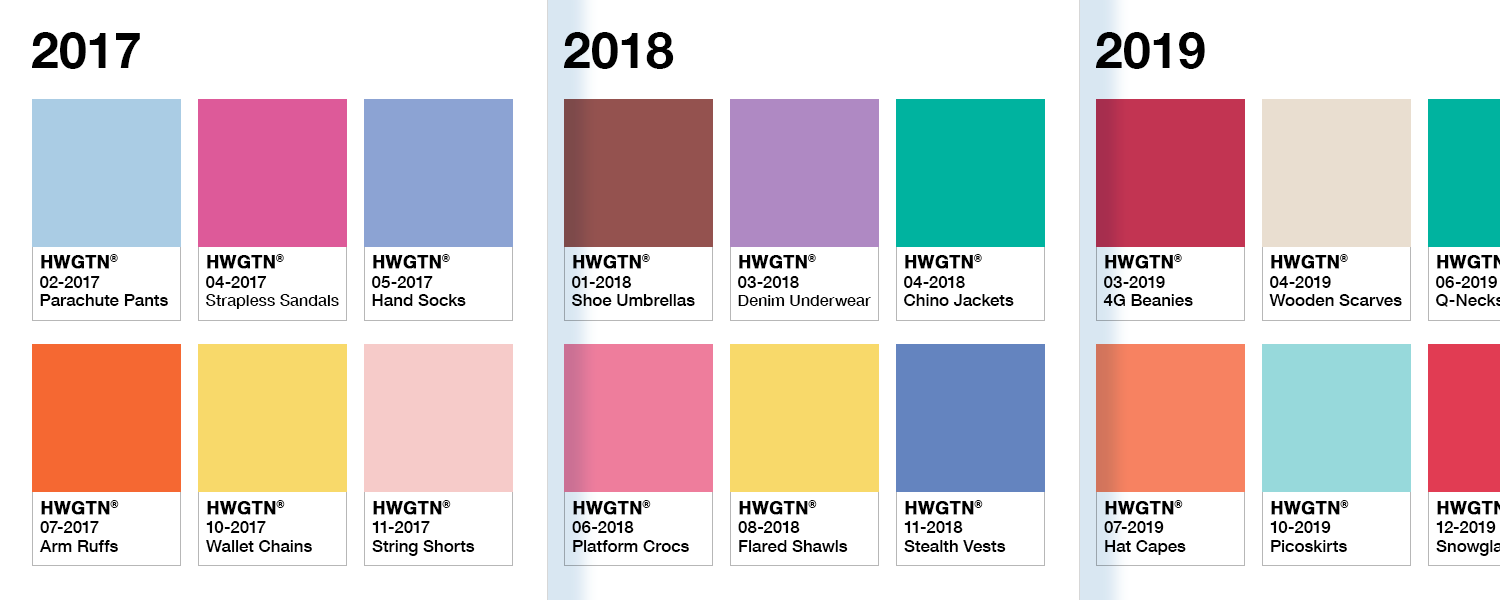

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Sartorial section, which looks at the impact of science and technology on how we present ourselves to each other. Click the logo to read more.