Read the next installment: “Links In a Network“

Read the previous installment: “The Ship‘s Cockpit“

Descending to the base of the accommodation block, below deck and behind a pressurized door I find the engineering control room. If the bridge above is designed for seeing around the vessel, the ECR is a machine for seeing the ship itself. It’s the other half of the ship’s command post. A long console of screens and indicators runs the length of the room, showing sensor readings of temperatures and RPMs. The wall behind is covered with buttons, levers, and controls for operating the ship’s systems.

Unlike the bridge, there is no view here. There are no windows or external CCTV cameras. No natural daylight; just fluorescent lights. There’s no sense of place or motion in the engine room. While “watching” the vessel arrive into port from the engineering room I continually ask if we’re there yet, unable to feel any change in movement. We could be anywhere. As one of the engineers jokes, the only time they see the sea in here is when it leaks in through a pipe.

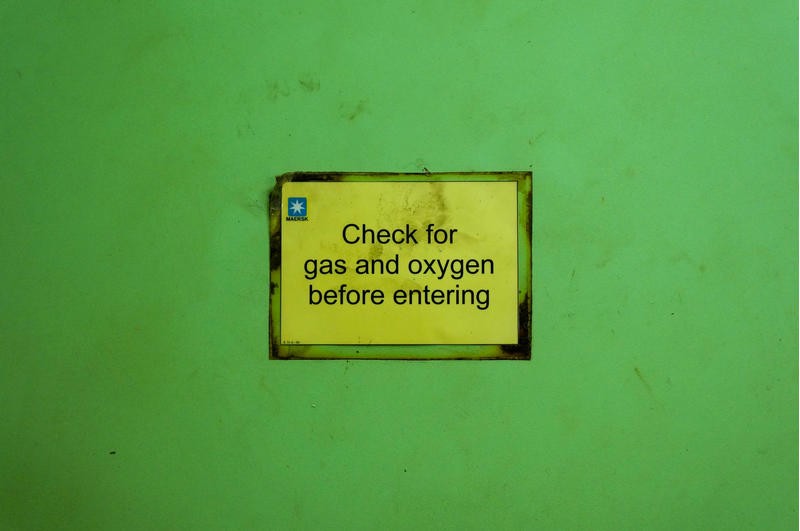

It’s much like any mechanical engineering workplace I’ve been inside. There are endless health and safety posters. There’s a break table with a tin of biscuits. There are manuals, including the hefty blue “Machinery Operating Manual.” Every few minutes the door to the adjoining engine room opens as a member of the crew enters or exits, a burst of heat and sound escaping into the control room.

The engine room is an extreme environment. The console shows it’s 40 degrees Celsius (or 104 degrees Fahrenheit) in there. The crew works inside only so long, pausing for regular breaks to rest and rehydrate. Anyone who spends time in the engine room takes salt tablets multiple times a day to recover what’s lost through constant sweating.

Inside the engine room, it’s loud. Over the sounds of the machinery I struggle to hear Chief Engineer Ivanyuk as he gives a tour. A ladder leads down several floors into the void where the main engine sits beneath the accommodation block, maximizing cargo space aboard the ship.

This is the only main engine, running 24/7 and propelling us on our voyage. It’s suitably proportioned for our big vessel: the size of a double-decker bus, spanning two floors of the engine room. Above the ceiling is a tangle of pipes running in every direction, like a Windows screensaver.

Behind the engine, through a mechanized sliding bulkhead door, is the propeller shaft. The meter-diameter metal rod drives the ship forward, constantly rotating. It’s cooler here. I can reach out and touch the cold hull on either side of the shaft, chilled by the seawater beyond.

The rest of the engine room is full of machinery: generators powering the ship and the valuable refrigerated cargo of fruit and meat; air conditioning and heating units; water sterilization systems; sewage-processing plants; oily water separators; vast fuel tanks; everything necessary to be self-sufficient for weeks at a time. All the infrastructure I take for granted on land is right here.

If anything breaks while at sea the engineering crew must be able to fix it. There are no repair garages out here. Storage rooms full of parts carry replacements for every essential component the vessel uses, down to every size of bolt and screw aboard. Massive replacement cylinders sit next to the main engine, under a gantry crane ready to lift them into place should they be needed. A fully equipped workshop allows for custom repairs.

Repair and maintenance is constant and ongoing. The engine room seems designed with maintenance in mind, its ladders and steps welded into place, suitable for use even when the ship is rocking.

When I boarded the Maersk Seletar in Busan the engineering crew was in the middle of lifting a replacement pipe aboard. The heavy precision-welded cylinder was a replacement for a cracked pipe in the engine room, in need of one more permanent next time the ship’s busy schedule allows. It’s hard to imagine an autonomous drone ship as able to function in such a harsh sea environment without a crew in place to constantly battle its entropy.

The engineering crew is so important to the functioning of the ship, in fact, that they have equal ranking to the deck crew. Across the corridor from the captain’s quarters is the chief engineer’s cabin, of identical proportions. The ship is a machine designed to optimally transport containers, but without the crew it cannot operate.

Nowhere aboard is it clearer that we are living and working inside a vast machine than in the engineering control room.

Read the next installment: “Links In a Network“

Read the previous installment: “The Ship‘s Cockpit“

Please note that this work is not available for republication under the terms of a Creative Commons license, as per most of our other content.

Postcards From A Supply Chain follows Dan Williams as he traces consumer goods back through the global shipping system to their source. It was organized by the Unknown Fields Division, a group of architects, academics, and designers at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London.