Read the next installment: “Fix What’s Broken“

Read the previous installment: “The Uncertain Logistical Life“

Drifting off to sleep, I’m awoken by an alarm from next door in the ship’s meeting room. These alarm boxes are mounted in every cabin and communal room on the ship. They’re smart enough to know who’s on duty for which type of problem and will sound in only the right places. I check the display on the one in my cabin.

I try to decipher the acronyms and abbreviations on the screen. Some kind of failure? A problem with the main engine? We have only one main engine for propelling the vessel; there is no secondary, no backup. I take the stairs up to the bridge–the ship’s control center–passing Second Engineer Thottempudi as he is catching the elevator down to the engineering control room below deck.

The bridge is dark. I have to stand still and wait for my eyes to adjust so I don’t bump into anyone. The lights are switched off at night to help focus on the unlit sea ahead. All the displays and lights in the console have been switched to night-mode, with dimly lit screens and green-on-black user interfaces. Instruments that are too bright have tracing paper taped over them. Even the kettle is illuminated by a faint red light bulb instead of a white one.

It’s quieter than usual. The background hum and vibration of the engine is absent. Off to the port side occasional flashes from a lightning storm catch my eye. Ahead on the horizon are the blinding white lights of fishing vessels, their powerful lamps attracting squid and fish to the surface.

I can see the helm steering us out of a shipping lane, the crew calmly following procedure. There’s no chatter, only precise commands and confirmations. Within a couple of minutes the engine has restarted, and control is returned to the autopilot as we continue along our original course. Second engineer Thottempudi explains that the engine is fine; there was just a problem with one of the many sensors constantly monitoring its condition. I return to bed.

During breakfast the next morning the captain pops by to update us on the voyage. “Bit of a disaster last night,” he begins. The engine failure? “Oh no, not that. That happens occasionally.” OK then. So what disaster? “The email’s down”–the kind of thing that might be considered a disaster in any office building, only this one is traveling at 10 knots.

I hadn’t expected email to be so important aboard, but it’s how the ship receives its instructions from the operations office. Without it we are uncertain of our fluctuating berthing times and changing course. Thousands of containers of international cargo traveling aimlessly while someone in Denmark fixes a mail server.

There’s a desktop PC, named Seagull, embedded in the bridge for checking and replying to the ship’s email account. It’s not uncommon to find the officer on watch standing here performing admin work as autopilot guides the ship. The ship’s radar warns of any potential collisions and can divert from course to prevent them. It’s even clever enough to take into account the velocity of other vessels.

The bridge on a modern ship is much like the flight deck of an airliner. Like an aircraft, the ship carries a black box, the Voyage Data Recorder. It records everything, even all the naive questions I’ve asked the officers, through an array of microphones in the ceiling. Should the vessel sink, the black box would float free from its mount on the monkey island above the bridge.

Occasionally the vigilance alarm chirps, checking that the autopilot is not running unsupervised, requiring whoever is on duty to press a button. Sometimes it feels like the officers are merely supervisors, albeit ones who have trained for years and sat through countless examinations. They stand for hours, feet unthinkingly shoulder-width apart for stability, keeping watch. The bridge’s two seats are used only when the seas are too rough to stand.

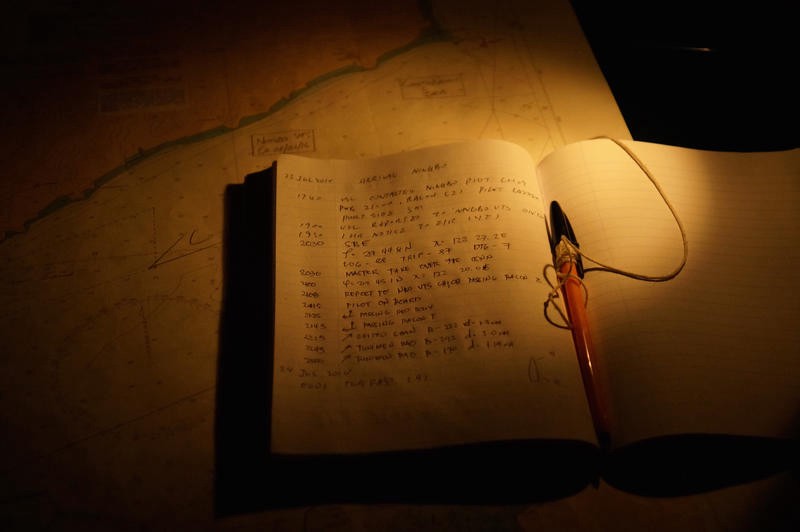

The deck crew isn’t made redundant by this automation. The autopilot handles the simple cases, traveling long straight stretches out at sea. People still perform the coming-into-port navigation. And there are plenty of non-navigational tasks for them, too. Someone still has to plot a course for the autopilot, keep logs, monitor the cargo, and on and on.

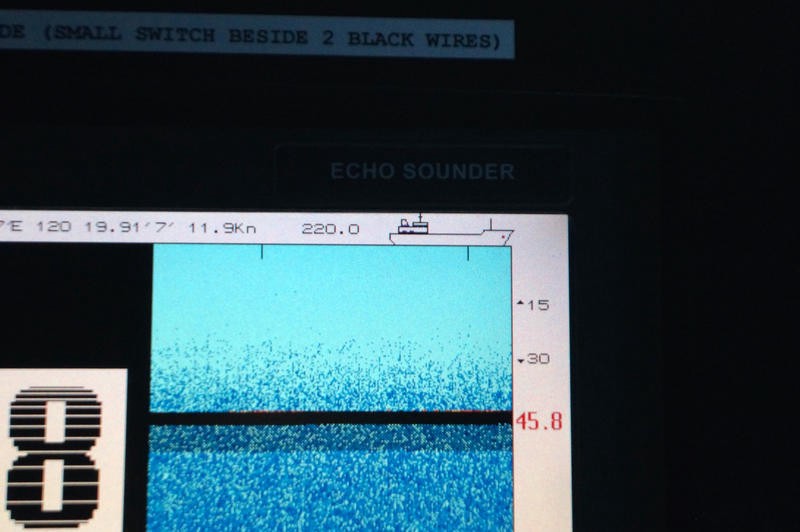

Likewise, the bridge’s advanced digital systems haven’t replaced more analog tools. Below the digital echosounder display there’s a dot-matrix printer outputting depth logs. Our course is charted in the ECTIS (electronic charts), but the path drawn in pencil on a paper chart is still considered the definitive version. While we transmit out velocity and position on an AIS transponder, we also have a neatly arranged cupboard full of communication flags. Chart updates arrive as both a file on a CD and as paper patches to apply to physical charts. New technology doesn’t replace older equipment–it layers on top of it.

The captain has seen a plethora of instruments appear during his career at sea, new ways of seeing, controlling and communicating. Among the biggest advances is GPS, the ability to know where the ship is, down to a precision of meters. This, however, only became commonplace as recently as the early 90s.

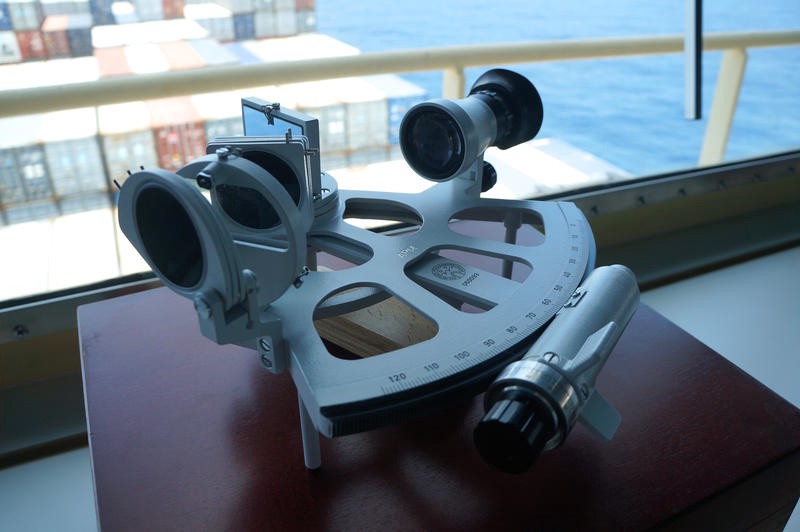

Prior to that the crew relied on a mixture of dead reckoning, some radio navigation systems like Decca and taking sights on a sextant. When I ask how a sextant works the captain offers to demonstrate. “We’ve got one here,” he says, opening the cupboard labeled “Charts” and removing a wooden case from between the computers running the electronic charts. Inside is a modern sextant, a precision optical instrument.

The ship is required to carry it and the deck crew has to know how to use it. Just like the redundant pairs of radar, autopilot and electronic charts, there are two sextants on the bridge, plus a few other navigation tools like an azimuth circle.

So, if the bridge positioning system fails, it’s back to navigating by the stars? Not quite, the captain replies. “If the GPS failed, I would use my iPad instead.”

Read the next installment: “Fix What’s Broken“

Read the previous installment: “The Uncertain Logistical Life“

Please note that this work is not available for republication under the terms of a Creative Commons license, as per most of our other content.

Postcards From A Supply Chain follows Dan Williams as he traces consumer goods back through the global shipping system to their source. It was organized by the Unknown Fields Division, a group of architects, academics, and designers at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London.