The foundations of every medical diagnosis are (clears throat) the patient’s history and the physical examination. We’d likely conjure the same image, you and I: you tell me when the chest pain started (the history); I stethoscope around your anterior and posterior chest (the physical); and eureka, the diagnosis–you’ve got pneumonia. There might even be lab work or imaging along the way. But in psychiatry and neurology, interpretive pictures have long been part of this process, with varying levels of accuracy.

Many of these pictures are bizarre and hilarious and surreal. Let’s look at them together, starting with the big one:

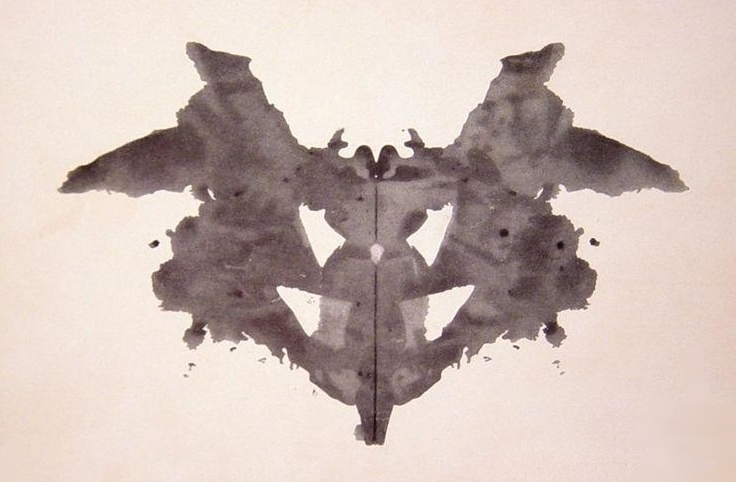

Rorschach Inkblot Test

I assume that the above inkblot is familiar to you. The Rorschach inkblot test has a level of cultural saturation that has led, in my opinion, to some overpromising:

Growing up, Hermann Rorschach loved playing a then-popular game called Klecksographie. The game encouraged players to collect inkblot cards and to make up stories about them. Klecksographie’s most famous fan later played it with his patients, noticing that those affected by schizophrenia made different connections–sometimes radically so–than a majority of people. (The origin story, so far, seems straightforward.) Rorschach ended up painting his own inkblot series, developed them as a diagnostic test for schizophrenia, and, in 1921, published his findings. He died in 1922, but his 10 blots lived on, and were used to assess seemingly every domain of a person’s personality, thoughts, feelings, actions, and motivations–the test was “hyped as an X-ray of the soul.” But, it turns out, there are problems with using a series of abstract inkblots for diagnostic purposes. Good ol’ Wikipedia helpfully provides a list:

The objectivity of testers, inter-rater reliability, the verifiability and general validity of the test, [the fact that the] bias of the test’s pathology scales towards greater numbers of responses, the limited number of psychological conditions which it accurately diagnoses, the inability to replicate the test’s norms, its use in court-ordered evaluations, and the proliferation of the ten inkblot images, potentially invalidating the test for those who have been exposed to them.

In 2013, some hardcore Inkblottos (I’m trying this term out) published in Psychological Bulletin a meta-analysis of all the published research on the inkblot test and claimed to identify excellent support for the usefulness of the test in assessing 13 variables, from situational stress to information processing to suicide.

Another group of scientists, led by Richard Taylor at the University of Oregon, found that the more complex the blot, the fewer interpretations it carried. Taylor is not a psychologist but a scientist trying to build a bionic eye, and the research was to figure out how to make that eye interpret things more like our in-house pair does. The inkblots, with their high profile and bad reputation, are now almost 100 years old and crossing into new disciplines despite it all. Nobody can seem to really let them go. I respect this hustle.

(Here’s my inkblot: how ridiculously fine was young Dr. Rorschach? Please look at these pictures and tell me what you see while I sneak away for a milkshake.)

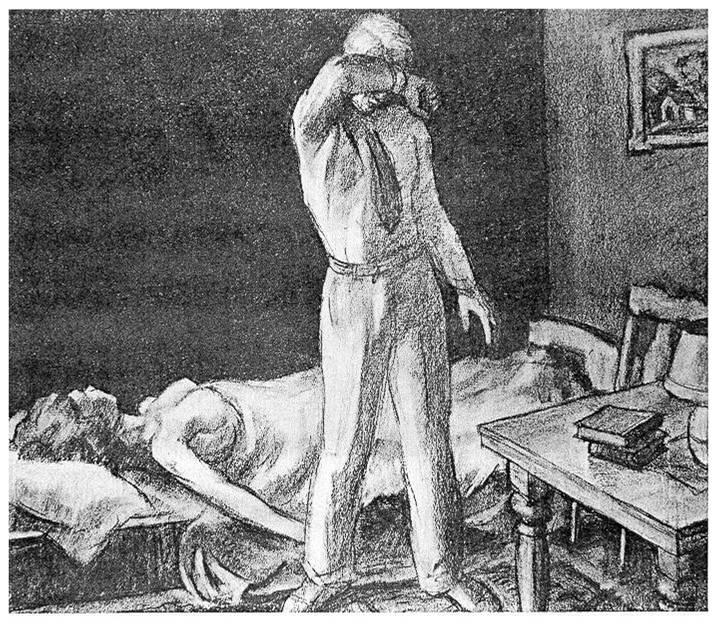

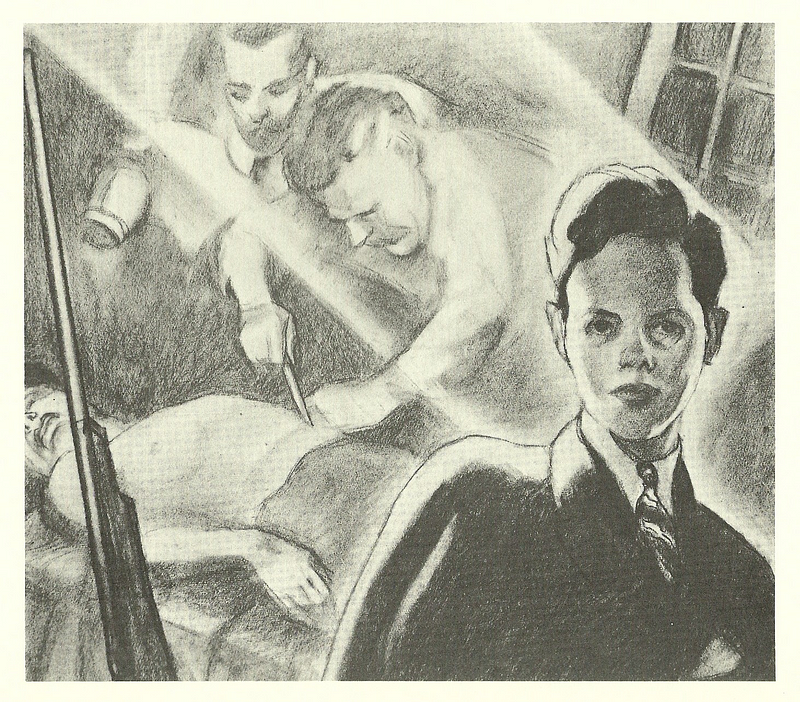

Thematic Apperception Test

The Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) is another set of weird, response-provoking pictures used to assess personality traits. Like the inkblot test, the TAT scores narrative responses, but is seemingly way easier to fuck up. Let’s take in card 13MF, above: crying, darkness, and boobs. You can’t “a butterfly?” your way out of this one. (Press your luck with a scored, short version here.)

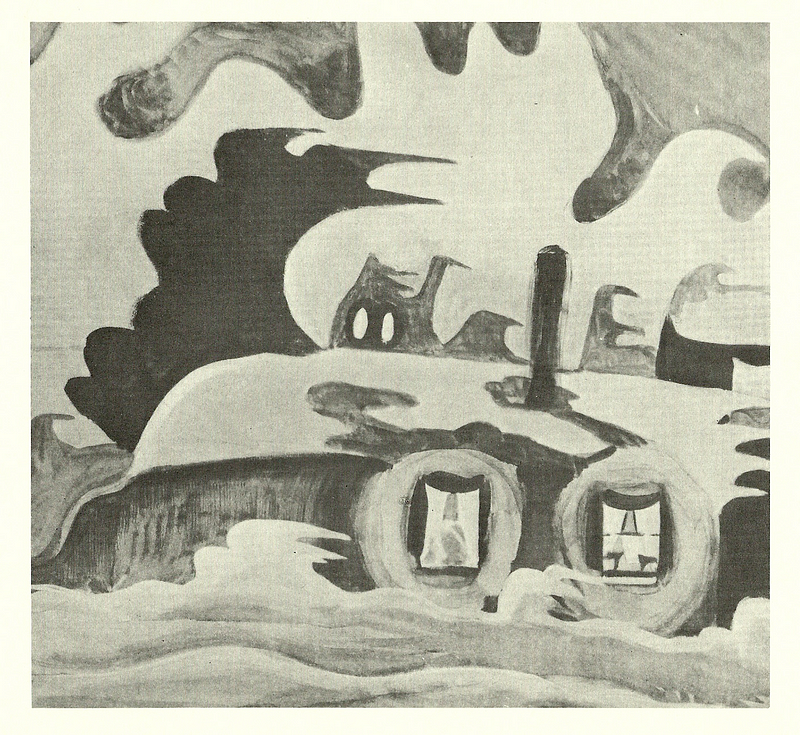

The TAT images are mostly aggregated from pre-existing works, with their own histories, which are kept from the patient. Take this card, a black-and-white reproduction of a 1918 watercolor by Charles Burchfield, “The Night Wind”:

And its story: the watercolor re-creates the artist’s childhood impression of supernatural beings flying over a next-door neighbor’s house.

Other cards include, uh:

The same criticisms of the Rorschach test apply to the TAT–too ambiguous, too leading, with soft results–but not every picture has these faults.

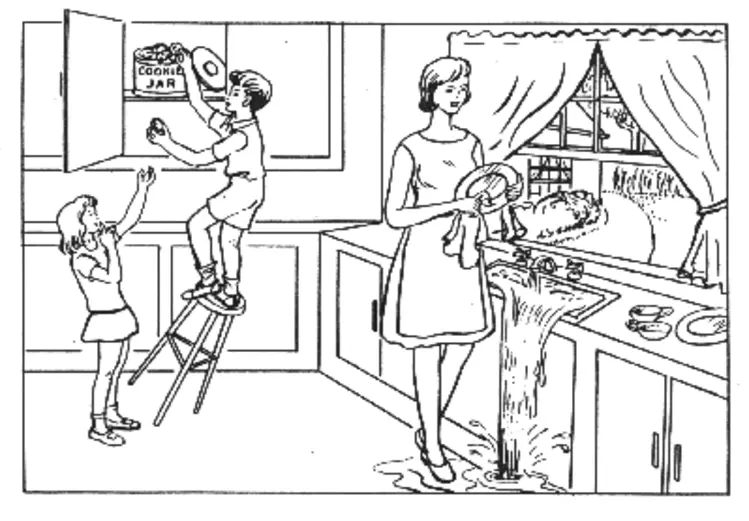

Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination

If I’m being honest: the image “Cookie Theft,” from the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination, or BDAE, is my favorite diagnostic test. Let us gaze upon this simple line drawing depicting childhood misbehavior (left) and passive-aggressive maternal coping mechanisms (right). It is pure fucking science, converting the story someone tells about a picture (“description task”) into diagnostic data assessing the presence and severity of multiple language and cognitive disruptions.

Let’s start with the picture’s original purpose, as part of a set of examinations for aphasia. In the 1970s, Harold Goodglass and Edith Kaplan, a psychiatrist and psychologist, respectively, theorized that analyzing specific speech aspects could exactly isolate misbehaving neurological anatomy.

As with the inkblot test and the TAT, Goodglass and Kaplan’s BDAE asks patients to look at the picture and describe what they see. Different aspects of the response are counted; in semantic dementia, for example, their words may be meaningful but few in number. For fluent aphasia, someone may talk fluidly and without hesitation but choose meaningless words.

“Cookie Theft,” in particular, also tests visual extinction or spatial neglect: deficits exhibited when one lobe of the brain has been damaged, such as by a stroke. If you damage the right parietal lobe, the cabinet jailbreak in progress on the left side of the image disappears; in contrast, a brain damaged on the left side ignores Mom, just like ol’ Mom ignores her excruciating, ever-present, pre-Friedan emptiness. Or tries to!

“Cookie Theft” remains clinically valuable enough that some speech pathologists gave it a 2018 reboot, adding more current details. Dad is now blowing it while Mom mows the lawn. And they got a dog!

(P.S. The cookie thieves seem as if they live in the same cul-de-sac as the peg-people on Sunny Day Real Estate’s album cover for Diary, no?)

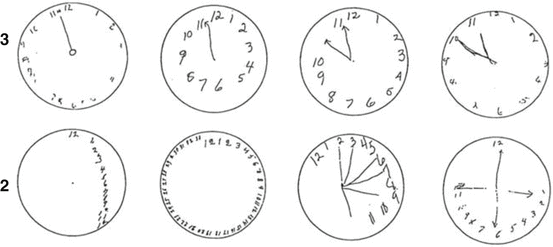

Clock Drawing Test

The clock drawing test (CDT) assesses cognitive impairments in older adults, including Alzheimer’s dementia and Parkinson’s; a 2018 study in the Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine compared it favorably to the “gold standard,” the much longer mini-mental state exam (MMSE). (Try the clock test out yourself!)

What is the experience of taking a test like this one? The basic I-do-this-every-day simplicity of describing a picture or drawing a clock can also make exposing the deficit more painful. Carl Duzen, a former physics educator affected by Alzheimer’s, describes the experience in a recent episode of This American Life: “Why is this so difficult? Why is that so hard? It’s clocks. Why is that so hard?”

Diagnostic pictures are alluringly disruptive in a clinical age of trying not to do what doesn’t work. They are low cost, require no imaging equipment or blood work, and results are available immediately. The “Cookie Theft” test is so quick to perform–only two minutes at a patient’s bedside–that a 2018 Frontiers in Human Neuroscience study recommends it for stroke, as it can capture “an overall aphasia severity measure that correlates with percent damage to language cortex.”

When they work, diagnostic tests aren’t about tricking patients with “gotcha” questions. (It’s medicine, not a scene from Law & Order.) Inkblots may not be the “X-ray of the soul,” but they are good tools.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our “Health” Beat, which examines how we can increase access to and quality of health care across the globe. For more dispatches, click the logo.