Like many of my peers, I have spent much of my adult life unconsciously valuing security and certainty in my major life decisions. I believed I could set myself up to control what happened to me, and thus be certain of a good life. This is a belief so deeply ingrained in Western society today that it’s difficult to avoid.

A lot has changed for me lately, though. I’ve come to see things a little differently (more on this later). I’ve realized this control-based approach doesn’t work very well for me when facing the complexity of the real world.

This same bias toward certainty and control is playing out today in how we tackle some of the biggest, more complex issues facing our society. From global poverty to chronic disease, education to climate change, the common trend is to seek top-down, “command-and-control“-based solutions that are supposed to guarantee the results we want if only we engineer them well enough. More often than not, strategies following this mindset fail to meet expectations. We blame human nature or our failure to account for enough variables, and go back to the drawing board without examining our core assumptions.

It’s time that we let go of this obsession with control, in our own lives and in our approach to global problems. We are better served when we acknowledge that no central organization or plan will ever account for all the variables, nor provide a guaranteed fix to complex problems. Instead, we should recognize the uncertainty of the real world, and the imperfection of our planning and engineering. At the central level, we can provide incentives and support for a diversity of local actions that move us in the right direction; we can seek to better trust, teach, and understand each other so that our collective actions build and evolve toward our goals over time.

By now this probably sounds overly idealistic, woo-woo, a bit pie-in-the-sky, so I’m going to talk about how this plays out in practice with an issue close to my heart: climate change.

Climate change, the story so far: (A quick refresher)

- The scientific consensus is that excessive greenhouse gas emissions from humans are changing the Earth’s climate.

- As the Earth’s climate changes, the likelihood that very bad things will happen increases significantly (scientists predict more and worse natural disasters, massive drought, food supply collapse, rising sea levels, and the sixth mass extinction).

- The more greenhouse gas we emit, the more the climate changes, and the higher the risk becomes for these very bad things.

- A lot of activist and legislative activity focuses on putting a hard, enforced, and regulated limit (or cap) on greenhouse gas emissions, particularly carbon dioxide, to avoid the worst of the risks.

By controlling emissions at a certain level, the thinking goes, we can have control over the outcomes we see. On the surface, this regulated limit approach is a very attractive concept–we really want to avoid the very bad things. Surely any proposal that would provide certainty here is worth adopting, or at least looking at closely.

But seeking certainty about climate change through control is a trap, and one that many leaders and organizations in this space have been stuck on for many years. Why? A few reasons.

Reason One: The real world is a lot more complex than our models, and we can’t precisely predict the level of greenhouse gases at which the impact moves from “manageable” to “catastrophic.”

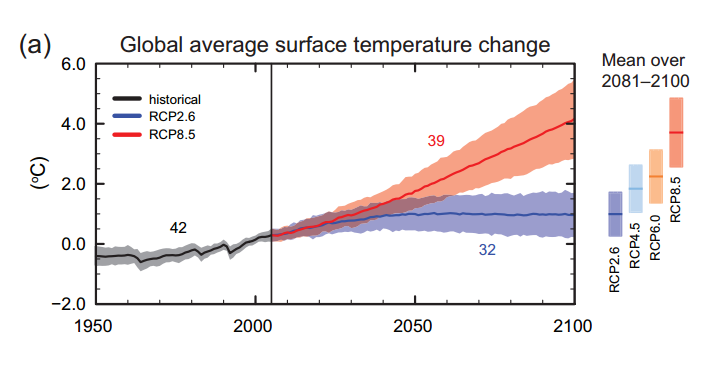

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), largely considered to be the consensus authority on climate science, periodically publishes a set of reports with the latest climate data and forecasting. The above graph from a 2013 IPCC report shows temperature forecasts for two potential emissions scenarios. For both, the range of uncertainty for possible temperature outcomes is nearly 2° Celsius. This may not seem like much, but expert modelers predict there is an astronomical difference in extreme weather outcomes between an average 2° versus 3° increase. Just getting to +2° could trigger massive extinctions, coastal flooding, drought, and food shortages.

Even if we restricted emissions to align with the more optimistic scenario above, there would still be huge risk to our society. Thus, any perceived certainty about the outcomes through controlling emissions levels is really no certainty at all. With the number of variables and possible trigger points involved, no realistic amount of improved modeling and prediction is going to precisely tell us the real danger threshold.

Reason Two: Control is expensive, burdensome, and sets us against each other.

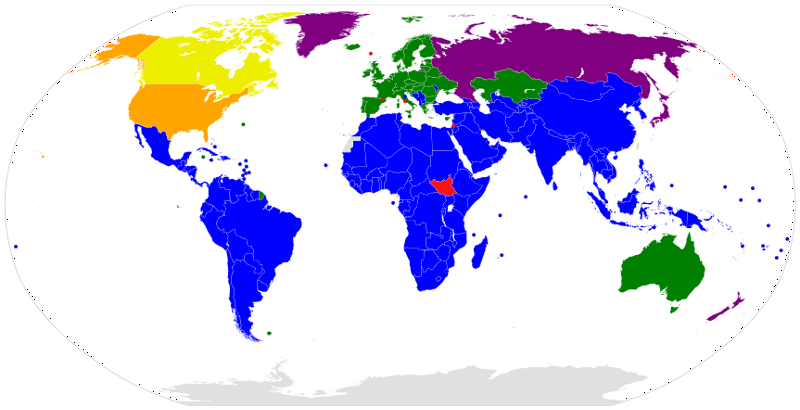

World leaders have been working on the Kyoto Protocol (which seeks binding emissions targets) since 1992. Almost 25 years later, only a handful of countries are still tracking binding targets (in green on the map above). And why would they? Measuring, enforcing, and reporting emissions through traditional means requires a large, expensive regulatory apparatus and pits governments against the businesses that support them, suggesting that polluters are the “bad guys” which need to be controlled.

Corporate leaders view this as one more obstacle to overcome in their mandate to produce profit for shareholders. The whole thing feels set up to make us opponents, exerting our power over the Other. No wonder research suggests that in the United States the Republican “climate denier” movement is largely driven by the fact that these big government regulatory solutions are anathema to many pro-business conservatives.

Why do leaders and prominent activists continue to advocate for control-based solutions?

In places like Washington state we have actually seen liberal, environmentalist, climate change-believing groups actively work against climate strategies that forego control in favor of market-based incentives, like the emission-reducing initiative I-732. Why is it so difficult to get these solutions on the table? I believe the answer lies in the roots of our Western culture, a survival strategy that has been reinforced–especially in the past 100 years: We deeply fear uncertainty, and when faced with it we do everything in our power to assert control over our surroundings.

Our whole culture is built on this idea of controlling our lives and our destiny. From the time our ancestors first began to cultivate and store crops to control their food supply, they managed a shift from a nomadic lifestyle to one that was seemingly less exposed to the uncertainty of shifting seasons and natural disasters. Today, we see the same trend in older generations’ desires for stable jobs and marriages above most other priorities. They’re a hedge against uncertainty.

The control-based structure of most corporations follows from those principles established during the Industrial Revolution. It all reaches its logical end with the current corporate culture of rigid, fixed office hours and dress code that values the boss’s perception of control more than the overwhelming evidence that this practice is actively counterproductive.

The thing is, in most cases beyond trivial complexity, this sort of “control” is an illusion that makes us feel safer but ultimately less resilient to the unpredictable happenings of real life.

This point was made really clearly in my own life last year when a major, unexpected loss suddenly shattered a multi-year life, career, and relationship plan I had, forcing me nearly back to square one. These moments in our lives drive home the fact that no amount of planning or maneuvering can ultimately determine the direction of our lives, and the same is true for our collective decisions and our planet. Catastrophe can strike at any time. For myself, I am focusing a lot more now on flexibility and resilience rather than moving toward a specific plan.

So what should we do going forward?

This flexible, open approach can be used for tackling thorny problems that arise in our own lives as well as complex global issues like climate change. We can acknowledge uncertainty as our understanding of what is possible changes over time. Trust, enabling, and thoughtful incentives for local action will get us much farther than trying to control from the top, even though they provide no “guarantee” about the eventual outcome.

This is as true at the macro level as it is in our individual lives. In terms of central climate change policy, it suggests our best approach is to provide economic incentives, support, and collaboration to encourage everyone in the direction toward a better, cleaner world. We see this shift away from “command and control” to some extent already, both at the international and local levels.

Internationally, the COP21 Paris Agreements last November (generally considered very successful) arose through a similar strategy: Give each country autonomy to select its own emissions targets, based on trust and common interest, and flexible to evolving over time as technology and our understanding continue to progress.

Meanwhile, in the United States, many high profile folks are advocating for a price on carbon (and increased investment in clean energy technology). These strategies forego expensive, regulated control in favor of simpler, more transparent economic incentives and support to encourage action, innovation, and collaboration.

What do you think? Is this a real connection I’m seeing between the individual and the macro, or am I just projecting from my own life? I would love to continue the discussion in the comments section below or over on my blog.

Originally published at joshcarroll.xyz on March 9, 2016. The views expressed here are my own, but I do work with a group called the Pricing Carbon Initiative in the United States. Please note that this piece is not available to republish under the terms of a Creative Commons license, as per the rest of How We Get To Next’s content.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Nature & Climate section, which looks at how human activity is changing the planet–for better or worse. Click the logo to read more.