The biggest killer in the world today is not obesity or malnutrition. It’s not HIV, malaria, bird flu, or any other infectious disease. It isn’t war and it’s certainly not terrorism.

The biggest killer in the world today is air pollution. Airborne toxins and particles contribute to a huge range of diseases and conditions–from heart attacks, to stroke, to mental illness, to neurological and respiratory disorders. When you sum everything up, air pollution was responsible for 5.5 million deaths in 2015–equivalent to about 10 people dying every minute of every day.

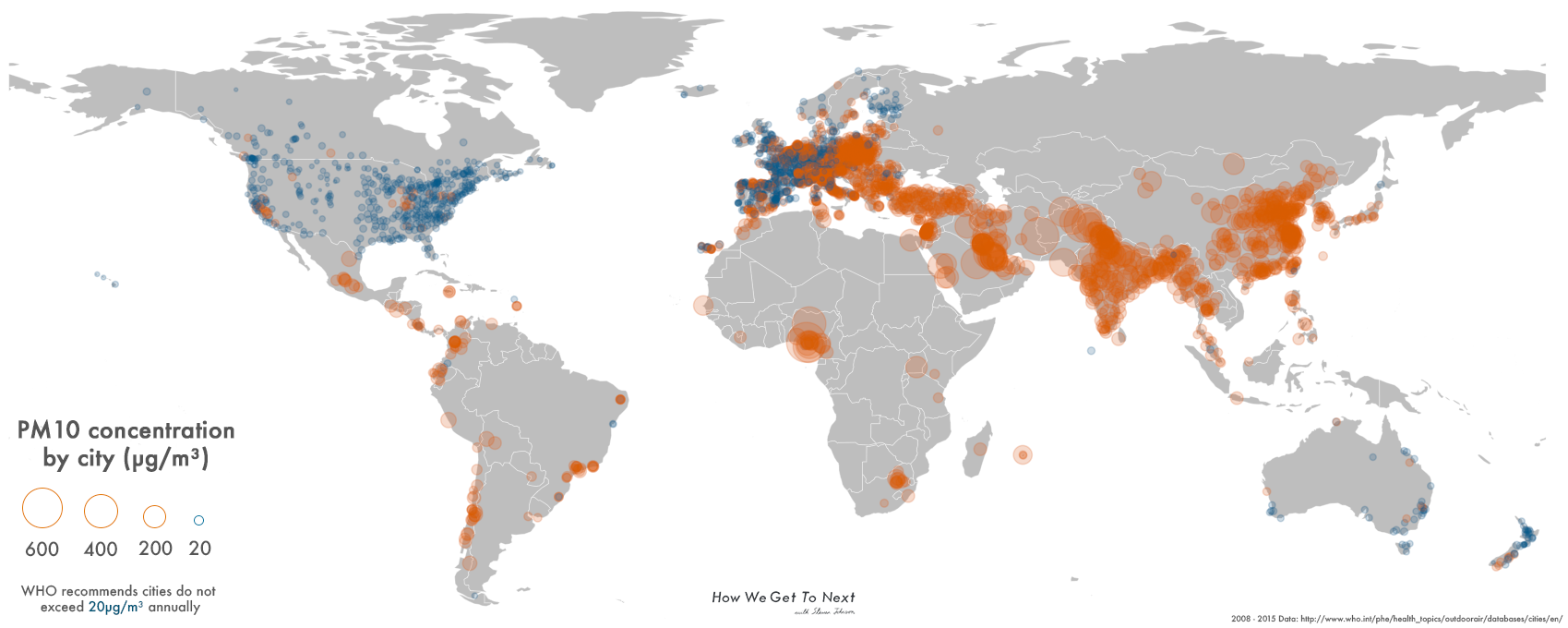

Almost half of the world’s population, and 80 percent of people living in urban areas, breathe air that the World Health Organization (WHO) says is unsafe for humans. In its latest analysis, the WHO surveyed more than 3,000 cities in 103 countries, measuring air pollution levels and the associated health impacts.

The data shows that the burden of air pollution lays heavily on the world’s poor. According to the WHO, 98 percent of cities in low- and middle-income countries with more than 100,000 inhabitants fail to meet air quality guidelines. In high-income countries, the figure is 56 percent. “When dirty air blankets our cities the most vulnerable urban populations–the youngest, oldest and poorest–are the most impacted,” said Flavia Bustreo, WHO assistant-director general for family, women, and children’s health.

When you talk about air pollution, you’re actually talking about a bunch of different chemicals that have a wide variety of effects on human health. One is called nitrogen dioxide, which is mainly produced by the combustion of fossil fuels–either in power plants or the engines of cars. As well as inflaming the airways of healthy people, and making the symptoms of asthma worse, it also creates ozone–which causes eye irritation and damages respiratory tissues in the body.*

Another is sulphur dioxide, which comes predominantly from power plants burning coal and oil (though volcanoes naturally pump a large amount into the atmosphere, too). Inhaling sulphur dioxide can worsen respiratory diseases, cause difficulty in breathing, and has been associated with premature births. It also causes acid rain, which dramatically decreases the ability of an ecosystem to support plant and animal life.

Then there’s what environmental scientists call “particulate matter“–usually abbreviated to PM. These are tiny particles from a wide variety of different natural and man-made sources–mineral dust, soot, smoke, ash, sea salt, and even pollen. They’re normally divided into two categories–those smaller than 10 micrometers (PM10) and those smaller than 2.5 micrometers (PM2.5). Anything larger tends to fall out of the atmosphere quite quickly under its own weight.

Particulates are probably the deadliest form of air pollution, as their small size allows them to penetrate deep into our lungs. In 2013, a study of nearly 313,000 people across nine European countries showed that there isn’t really a “safe” level of particulates. For every 10 micrograms of the larger PM10 particles per cubic meter of air, lung cancer rates rose 22 percent; for every 10 micrograms of the smaller PM2.5 particles, lung cancer rates rose 36 percent.

The smallest particles–those less than 100 nanometers in size (PM0.1 if we’re following the same naming convention, though they’re usually just called nanoparticles)–are the most dangerous of all. These tiny specks of matter, produced most commonly in diesel engines (hello, Volkswagen), can carry carcinogens on their surface and are small enough to pass through cell membranes and migrate throughout the body. Worryingly, we don’t yet have many large-scale studies about their effects on humans.

Here’s some good and bad news. The bad news is that air pollution is not something individuals have much control over, so there’s little you can personally do to clean up your air beyond trying to drive less (or wear a face mask, as many people in Asia do).

The good news is that governments have a lot of control over this problem. Historically, international treaties have proven hugely effective in controlling air pollution–particularly when it comes to air pollution that crosses borders.

National and regional regulation has also proved successful. Over the past decade or two, the United States, the European Union, and Australia have all begun major industrial pollution control programs, reduced fossil fuel consumption, and improved fuel quality in the transport sector. As a result, all three regions have reduced air pollution-related deaths by at least 24 percent since 2000.

“Reducing industrial smokestack emissions, increasing use of renewable power sources, like solar and wind, and prioritizing rapid transit, walking and cycling networks in cities are among the suite of available and affordable strategies,” wrote the World Health Organization earlier this year.

While most progress has been seen in the West, the developing world is making notable strides, too. The government of Delhi, one of the world’s most polluted urban areas, recently banned diesel cars from the city–though it has been forced to roll back that ban somewhat following widespread protests, illustrating the challenges that lawmakers face when enacting this kind of legislation.

Ultimately, air pollution is a tricky but solvable problem. Governments willing to regulate heavy industry and transport are seeing a huge boost in public health, which in turn cuts medical bills and makes their populations more productive.

Yet the more research that takes place, the more the problem seems to grow. One recent study showed that international shipping is a massive contributor to air pollution, especially in the coastal regions of East Asia. Hong Kong, the world’s busiest port, gets 42 percent of its PM2.5 emissions from the maritime sector, which is also its largest source of nitrogen dioxide.

Food cultivation is also a problem. A recent study shows that the agricultural sector creates more particulate matter than all other human sources. By feeding the world, we’re also slowly killing it. Addressing problems like this, in particular, will be a real challenge for politicians.

Another awkward fact is that both man-made and natural air pollution cool the climate. By obscuring the sun’s rays as they pass through the atmosphere, tiny particles of pollution diminish the energy that arrives at the surface. That means cleaning up the skies will worsen climate change, requiring us to redouble our efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (though by reducing fossil fuel burning, both problems can be solved at the same time).

There couldn’t be more at stake. Global air quality is terrible, and getting worse. Only rich nations with the resources to confront the problem head on have been able to respond effectively–and even then only in their backyards–while the poorest countries are being left far behind.

When other tragedies strike–disease, famine, war–we offer aid and assistance to those in need. But there’s no global fund for air pollution, a problem that’s killed more than 50 people since you started reading this article. There’s no major charity that dedicates itself solely to cleaning the world’s air. There are no rock concerts promising to make bad air history.

Why not? Is it because air pollution’s effects are insidious and do their damage on a timescale of decades, rather than weeks? Or because smog doesn’t yield attention-grabbing photos that you can put in a newspaper? Maybe it’s that the influence of big business on politics, particularly in the developing world, makes many solutions inconvenient for short-termist politicians.

I don’t know. But I do know one thing–without action, millions more will continue to die every year. We have the technology, the resources, and the moral responsibility to do something. We must make a start.

*Don’t confuse ozone at ground level with the ozone layer in the stratosphere. The former is a pollutant with nasty effects on human health; the latter is a beneficial natural phenomenon that protects the surface of our planet from damaging ultraviolet radiation.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Vital Signs section, on the future of human health. Click the logo to read more.