I’m old enough to have grown up alongside the music video. I spent my teenage years hunched over a VHS video recorder trying to record Duran Duran and The Cure videos from TV, cutting out the annoying presenters without chopping out any of the music. I remember setting the timer to record Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s “Two Tribes” video, which was so “shocking” that it could only be safely shown after midnight.

As an art student in the early 1990s living in a flat with cable TV (a real novelty in the United Kingdom at the time), MTV was on constantly. My final project was a computer-animated film, no doubt influenced by the sheer number of music videos that had entered my subconscious. Since I was supposed to be studying fine art photography, it meant I only managed a passing grade, but seeing as I got a career messing around with computers, video, and the internet out of it maybe it wasn’t wasted time after all.

As we begin this month’s How We Get To Next conversation about the past and future of music, I’ve searched YouTube (and the dusty recesses of my brain) to come up with a playlist of the most pioneering and innovative music videos you’ve probably never watched, but really, really should to see just how inventive artists have been with the format since its invention.

Norman McLaren–”Pen Point Percussion”–1951

McLaren was one of the most pioneering filmmakers of the 20th century, inventing new techniques that involved carefully painting his animations, frame by frame, directly onto raw film stock. A graduate of the Glasgow School of Art, he started as a documentary filmmaker for the postal service in London before moving to New York in 1939, where he first experimented with abstract animation and optical soundtracks. He relocated to Canada during the war years, where his work was funded by the National Film Board of Canada, and continued to innovate by making one of the first 3D films for the Festival of Britain in 1951 and winning a Best Documentary Oscar in 1953 for his anti-war film Neighbours.

“Pen Point Percussion,” a short film from 1951, demonstrates his revolutionary experiments in optical soundtracks–music made by drawing or painting onto raw film stock and running it through a movie projector. McLaren’s work is still fresh and exciting, and anyone working in moving images should know him. If you’ve never seen his films before, clear the rest of the day and dive into the archive of his work at the National Film Board of Canada.

Nam June Paik–”Global Groove”–1973

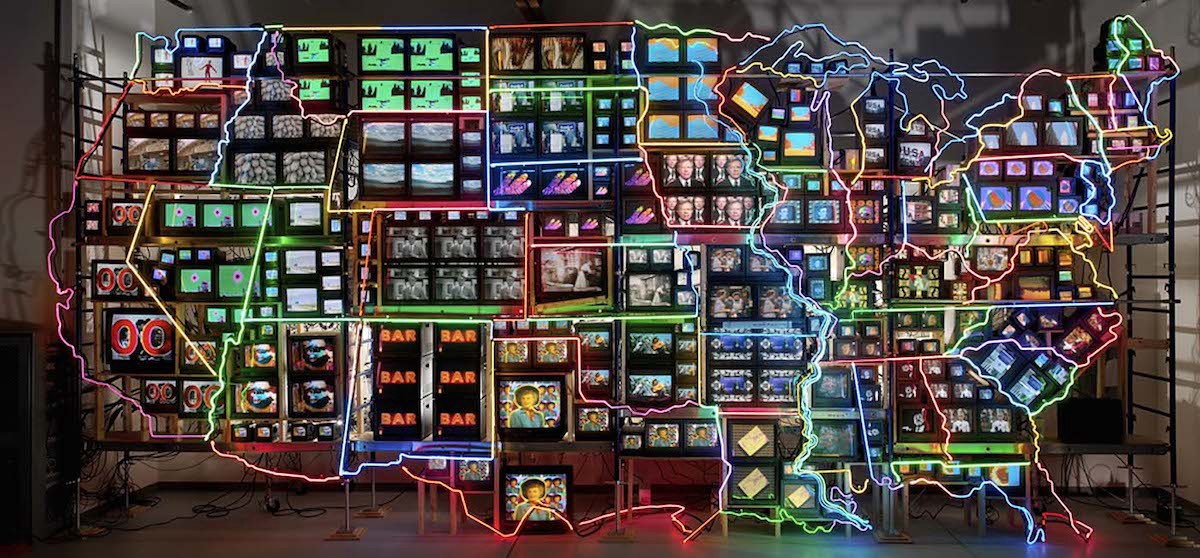

Nam June Paik was a Korean-American artist who started as a classical pianist, before meeting John Cage, Joseph Beuys, and other members of the Fluxus art movement while studying in West Germany in the 1950s. Heavily influenced by Marshall McLuhan’s theories about the power of mass media, Paik’s art looked at television as both a physical object (as in the performance of “TV Cello” with Charlotte Moorman, and in his installations that used magnets to distort TV pictures) and as a cultural force (he coined the phrase “Electronic SuperHighway” in the 1970s and later used the title for a major video installation, as seen at the top of this article).

This 1973 film uses early analogue video effects to animate two dancers. As Paik explains in the video, it gives a “glimpse of a video landscape of tomorrow when you will be able to switch on any TV station on the earth and TV guides will be as fat as the Manhattan telephone book.” It also has a fantastic soundtrack by Mitch Ryder & the Detroit Wheels.

Annabel Jankel and Rocky Morton–”Accidents Will Happen”–1979

In 1984, I was 12 years old and spent my hard-earned allowance on a copy of Creative Computer Graphics by music video pioneers Annabel Jankel and Rocky Morton. I’d just gotten my first home computer (a Dragon 32–named for its generous offering of 32 kilobytes of RAM) and pored over the illustrations of cutting-edge computer graphics. It introduced me to many legendary names–pioneers like Ivan Sutherland, Loren Carpenter, and the early work of Ed Catmull, John Lasseter, and the rest of the Pixar team.

Modestly, Jankel and Morton only included a reference to one of their own works in the book–the music video for Elvis Costello’s “Accidents Will Happen.” Although Dire Strait’s “Money For Nothing” of 1985 is commonly thought to be the first music video to use CGI, Jankel and Morton got there six years earlier. If you skip to 2:38, you’ll see a couple of seconds of vector graphics, recorded live as they rendered. It may be short, but it’s definitely first.

Herbie Hancock–”Rockit”–1983

In 1983, white rock artists dominated two-year-old MTV’s playlists. Their management teams had quickly realized the channel’s importance and lavished their clients with budgets for spectacular videos. Meanwhile, R&B and hip-hop artists were relegated to niche channels like BET.

Enter the unlikely heroes of this story–Kevin Godley and Lol Creme, who had left the band 10cc to start a career making videos for other acts. Herbie Hancock’s managers wanted to get “Rockit”–a new track influenced by hip-hop scratching techniques–on MTV, so they called Godley and Creme and told them to come up with a solution. Their pitch was simple–”Herbie Hancock appears on a television screen in a room full of robots. $35,000.”

It worked. Although the video is a nightmarish, Duchamp- and Dada-inspired hallucination of a domestic scene acted out by robots (some of them masturbating), it was a hit–and MTV put it on heavy rotation. This paved the way for Michael Jackson, Prince, and other black artists to push the boundaries of music videos on the same platform as their white peers.

Studio Moniker–”Do Not Touch”–2013

Over the last 10 years, the internet and social media have enabled a new generation of interactive music videos, from the YouTube cut-ups of Kutiman to Chris Milk’s hugely innovative work with Arcade Fire and Beck.

But if I had to choose one interactive video, it would be “Do Not Touch,” made by Amsterdam’s Studio Moniker for the little-known band Light Light‘s track “Kilo.” Although Chris Milk’s big-budget projects have had more publicity, I sometimes feel like they wear their innovation a bit too heavily. As all magicians know, the gimmicks are not supposed to be visible–it’s the story you tell that’s most important.

“Do Not Touch” is much more elegant. It uses a clever technique to capture the position of users’ cursors and then builds this into the next render of the video. This little trick tells the story in the video via a series of simple, fun experiments. Like the best music or gig, it makes you feel like you’re part of a crowd, and the moments when the video reveals truly crowdsourced visuals are hugely pleasing.

It might not take over your browser or use complex 3D virtual reality, but for me, this is the most aesthetically successful interactive video anyone has yet made.

I think it belongs in the music video hall of fame along with our other pioneers–McLaren, Paik, Jankel and Morton, and Godley and Creme. You might not know their names, but they’ve fashioned the way music and video have worked together over the last half century.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Fast Forward section, which examines the relationship between music and innovation. Click the logo to read more.