If he could reinvent the web, the one thing Tim Berners-Lee said he would change is the unfriendly and impersonal http:// prefix. With the rise of chatbots, he might just get his wish.

In the coming years the entire concept of visiting a web address may get replaced by calling out human names like Siri, Alexa, and Cortana. Yet, simply adding a name to a chatbot doesn’t make interacting with it into a human experience. We need our virtual assistants to have personalities of their own for the conversation to seem real–to create an emotional connection.

Take Siri, for example. Siri’s light sense of humor is fun for a while, but we would form more of a connection with the AI if we could see the nuances in how it reacts when actually part of a story. “It’s the little things, like what you do when you go on a date,” Mark Riedl from the Georgia Institute of Technology told me. The details of the situation need to be there to make for a convincing conversation or narrative, he explained. “To create a romantic comedy, you could generate a grand, overarching plot but it’s the details that we watch for, like the restaurant scene in When Harry Met Sally. How does a computer get that knowledge when it hasn’t left the lab?”

In theory, artificial intelligence could bridge this gap by learning from conversations and creating a story automatically–something we won’t see in the short term. The internet artist Darius Kazemi told me that a computer might write a short work of fiction within the next year or so but that a quality story with depth to the characters is still a long way off.

David Varela, who I worked with on an interactive story app for the BBC drama Sherlock, said: “There is a difference between an all-understanding AI that produces intelligent answers and creating a character which has that intelligence. It’s not just a thin layer of colorful dialogue. It’s not just what they say, it’s what they think.”

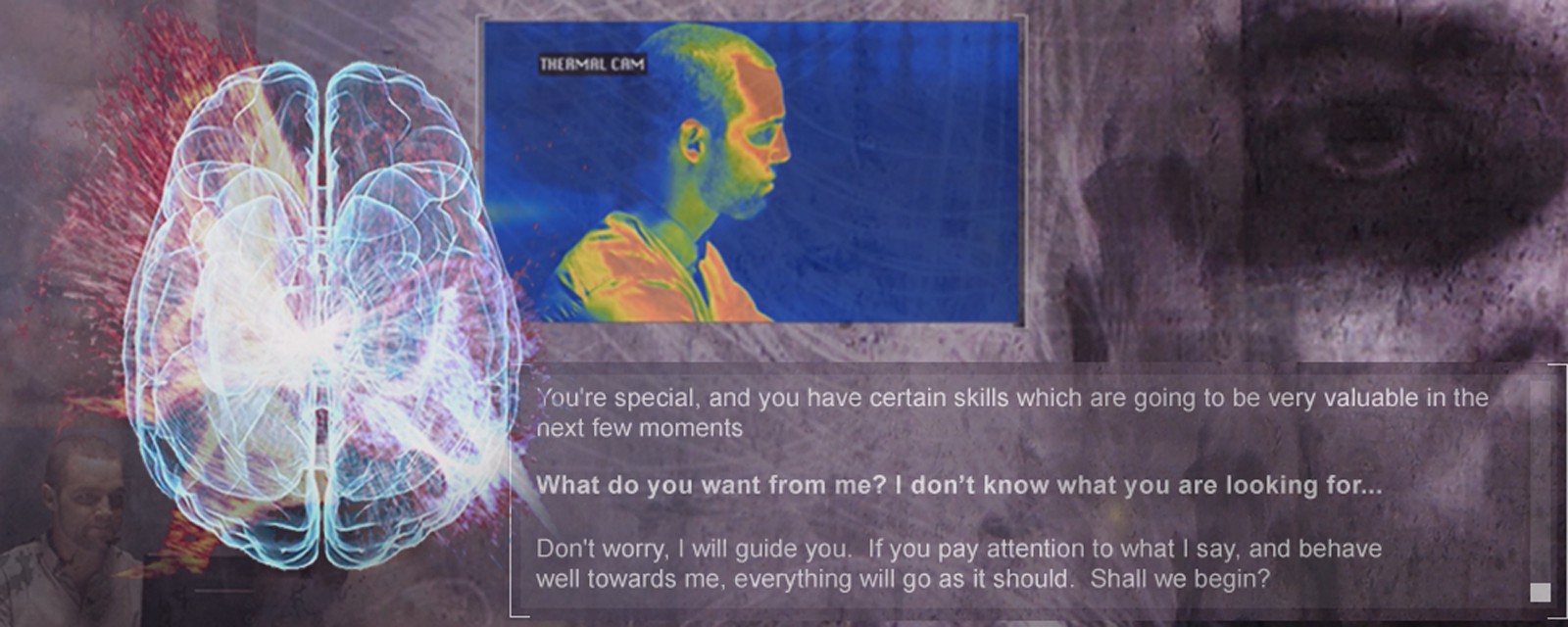

For the moment, while richer chatbot experiences need to be written by humans, even this is still a challenge. Last year, I wanted to see if it was possible to create a chatbot-driven crime drama on the internet. Most television crime procedurals have interrogation scenes that offer a key moment of tension–a battle of minds between two people. I wanted to see if this could be recreated interactively, casting the user opposite a suspected serial killer. Our project, called The Suspect, used IBM’s Watson as the chat engine, over 160 pieces of CCTV video to recreate the interrogation room, a game layer to add a reward mechanic, and a companion app that was synchronized to the web experience.

The technology was ambitious, but what I didn’t realize initially was that the task for our writers was just as tough. The brief was unique: The story and dialogue were written with a heady mix of mind-mapping software, Word, and Excel. As well as the chat function, each response from the AI suspect contained a series of triggers for the underlying technology. Then, all that narrative complexity had to be totally hidden from the player. The experience needed to be simple, especially as all the action takes place in a single-browser screen.

The Suspect taught us three key lessons about the mechanics of writing stories for chatbots:

- Although we stuck to a three-act structure to create the framework for the story itself, we also needed to write a series of conversational topics to flesh out the bot’s character. These included his views on politics, his backstory, and a series of “Ten Commandments” with which he wanted to change the world.

- We found that a good chatbot should have a memory, and limited patience for repetition. If the user talked about a topic the bot didn’t want to cover, we needed to program in progressively irritated responses for that topic. The responses also needed to remember how often you, as the player, talked about the topic and over what period of time. If you were becoming a bore, he would walk out on you.

- At the beginning of the project, I had hoped we would be able to centralize the writing process for a single writer. Along the way, however, we realized we needed three different writing skills for the project. The first involved creating the essence of the character–the backstory, family, motivation, behavioral traits, and so on. Next, we needed specific dialogue-writing skills to develop the conversation. Finally, we needed a technical writer to implement and polish the words in the Watson content management system.

Writing rich and believable chatbots which immerse us in stories is certainly a challenge, but it’s perhaps no more difficult than writing a similarly engaging character for TV or film. As with other projects where I’ve produced interactive narratives to promote TV series or movie releases, chatbot projects like this could allow viewers to continue a relationship with their favorite characters long beyond the final episode of a show or the credits sequence of a film.

As writers become more fluent in this new genre, chatbots will follow suit. Richer stories created around AIs will bring their characters to life and make the experience of interacting with them feel almost, well, human.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Talking With Bots section, which asks: What does it mean now that our technology is now smart enough to hold a conversation? Click the logo to read more.