This week China announced the construction of the largest animal cloning facility in the world. The target is to produce up to one million cow embryos per year to help meet China’s growing demand for meat.

Although I’m a clone myself (or is it my twin brother who is the clone?), the idea of one million cloned cows feels somehow wrong. We all know that farming is a deeply industrialized process, but the image of a field of identical cows, all with the same markings, tips over into the uncanny.

This is just another example of how we anthropomorphize farm animals. We want to see them as individual and cute–the stuff of story books and children’s songs–not think about why they’re on a farm in the first place. Meanwhile, we’ve been cloning crops, fruit, and vegetables for millennia. In fact, this is how many plants propagate–when a strawberry plant sends out a runner to create a new plant, it’s making a clone of itself.

When we grow a new plant from a cutting, we’re using a technique called vegetative propagation, copying the plant’s natural cloning abilities to develop variants that are more productive or aesthetically pleasing.

In the late 1950s, botanist Frederick C. Steward discovered how to regenerate plants using only one cell, a technique called micropropagation. This led to a huge growth in crop innovation, with scientists working to develop strains that were resistant to common blights and receptive to increased yields.

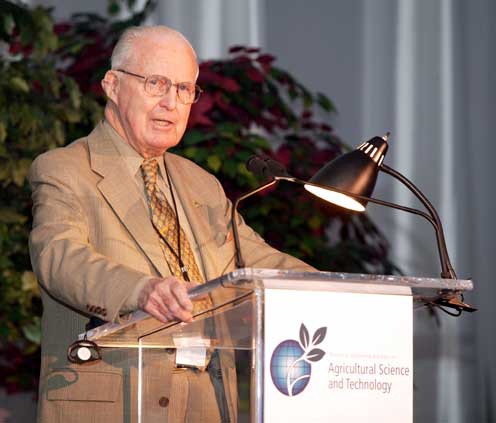

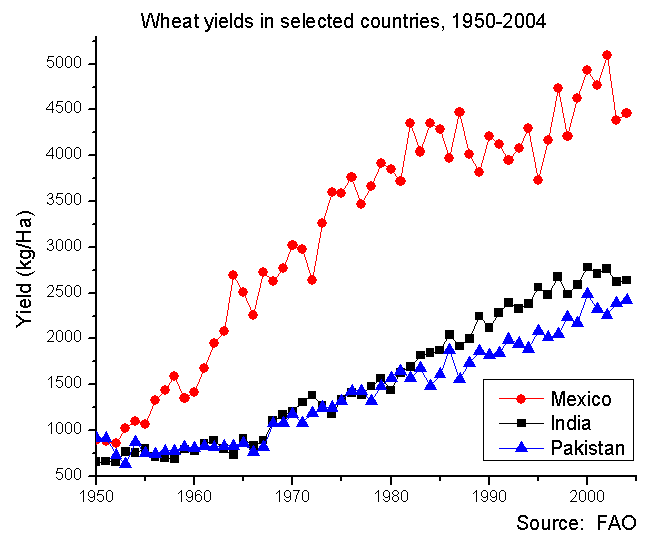

Plants typically have one or two genes that provide disease resistance, but in the 1950s plant pathologist Normal Borlaug invented “backcrossing,” combining hybrid plants with their “parent” lines. This technique allowed for the creation of plants with more disease-resistant genes, and made it possible to add more genes as new kinds of resistance were discovered.

Borlaug’s research was transformational. Starting in Mexico, where he worked in a DuPont lab supported by the U.S. government and the Rockefeller Foundation, his new crops led to a “green revolution” that helped developing countries feed their rapidly growing populations. By 1963, Mexico had gone from enduring food shortages to being a net exporter of wheat–all thanks to Borlaug’s innovation. He continued his research in India, Pakistan, and other developing countries, and was awarded the Nobel Prize for his work in 1970, by which time his wheat varieties were estimated to provide nearly a quarter of the world’s calories.

There are problems with cloning plants, however. If the vast majority of a particular crop is the same variety, it’s vulnerable to new or mutated diseases to which the crop has no resistance. This happened to the Gros Michel banana, the most common variety in the world in the first half of the 20th century. In the 1950s, Panama disease wiped out nearly all the banana plantations in Central and South America. Farmers had to quickly adopt a new variant, the Cavendish. This is the banana we buy in supermarkets and eat today, but it too is facing potential extinction from a new fungus called Fusiarium wilt. We might soon have to move to another variety, which could be a good thing–banana experts say the Cavendish is far blander and less creamy than the now rare Gros Michel.

So cloned plants are on our plates and in our fruit bowls every day, and have been for over half a century. But would you eat a cloned or genetically modified animal? In November 2015, the U.S. FDA approved the AquAdvantage salmon, the first genetically modified animal green-lit for human consumption. The salmon has added genes to boost its growth cycle, meaning it takes only 16″”18 months to reach mature size, compared to three years for wild salmon.

This wasn’t a quick decision–the salmon was first submitted to the FDA in 1995, and it wasn’t until 2010 that it got an initial recommendation for approval. Since then there has been a lot of opposition, with over two million public objections sent to the FDA. Campaigners are now preparing to take the FDA to court to stop the salmon from entering stores. Meanwhile, the European Union recently proposed tightening a ban on cloned animals, adding a restriction on all imports of cloned, reproductive material to the existing proposal to ban cloned animals from EU farms.

Thinking back to that image of a field of identical Chinese cows, I’m not sure I’d be happy putting a roast rib of cloned beef in the oven for Sunday dinner. I’m living proof that clones are influenced by both nature and nurture, but that doesn’t make me feel OK about eating one. Norman Borlaug’s work on cloned plants led to a green revolution and saved millions of lives, but the banana extinction of the 1950s showed there are problems with creating monocultures.

As developing economies cultivate a taste for meat, cloning might be one of the ways we can meet (excuse the pun) these rising demands. But instead of a Meat Revolution, we might end up with the first cow-extinction event. As someone old enough to remember the United Kingdom’s first “mad cow disease” crisis of the 1980s, that would be enough to turn me into a vegetarian.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our The Future of Food section, which covers new innovations changing everything from farming to cooking. Click the logo to read more.