Does money make you happy?

If you said no, you’re wrong. According to every metric, the wealthiest people in society are the happiest on average, and the poorest the least so. What’s more, people living in rich countries are much happier than those living in poor ones. For centuries, human society has been focused around making people and their nations richer.

Research over the last decade or so, summarized in a highly readable 2012 report from the New Economics Foundation, has shown that the full picture of money’s relationship with happiness is a little more complex, though. Emotional well-being–defined as “the frequency and intensity of experiences of joy, stress, sadness, anger, and affection that makes one’s life pleasant or unpleasant”–rises with annual income in the United States until somewhere around $75,000, at which point it levels off and other factors (health and marriage quality, most notably) become dominant.

Or does it? It turns out that the way in which you ask people how happy they are makes a big difference to the figures. If, instead of getting people to count and rate elements of their joy and sadness, you ask them to place themselves on a ladder where the top rung is the best possible life and the bottom rung is the worst possible one, the $75,000 leveling-off point disappears. People keep getting happier, all the way to the upper limits of annual incomes seen in the study–$120,000. Beyond that, who knows?

Characterizing the relationship between money and happiness is difficult, but what can be said for sure is that there are diminishing returns when salaries go up. A raise of $2,000 per year when you make $15,000 has a much larger effect on happiness than the same-sized raise on a salary of $50,000.

This idea of diminishing returns holds true when you look at country-level happiness data, too, though it gets more controversial. In a 1974 paper, Richard Easterlin argued that once a country passes a threshold of average income, more growth doesn’t generally increase average reported happiness. The principle became known as the Easterlin Paradox.

It was challenged in 2008 by Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers, who reassessed Easterlin’s data and found that in actuality no saturation point is ever reached–happiness merely increases more slowly than income. Stevenson and Wolfers also argued that absolute income contributes far more to happiness than relative income, pouring cold water on the idea of “keeping up with the Joneses.” Since then, the two researchers and Easterlin have traded new analyses, defending their respective viewpoints without reaching a firm conclusion.

So if we can’t land on a true answer about money, what else makes us happy? How about having children? Nope. People with children are less happy than equivalent people without children, and the level of happiness among parents doesn’t rise again until the kids leave home. Marriage does seem to make people happy, but it’s not clear if happier people are just more likely to get married.

Perhaps we’re just terrible at rating our own happiness? Again, no–it turns out that most people are pretty good at it. Psychologists have long compared the answers to questions like “are you happy?” with objective measures like heart rates, brain scans, and genuine smiles, and it turns out that people’s assessments are pretty close to the what the data shows.

Freedom seems to boost happiness. Enormous progress in civil rights for African-Americans in the United States has been made since the 1970s, and at the same time two-thirds of a very large happiness gap that existed between blacks and whites has disappeared.

But the same isn’t true when you look at women’s rights. Women had higher reported happiness than men in the 1970s, but that’s no longer true. Despite progress in pay discrimination, birth control, and childcare policies, women’s happiness across 13 countries studied has grown more slowly than men’s in recent decades.

Why? That’s a great question, without a certain answer. “We have several theories,” said Stevenson, who worked on the research. “There may be large-scale social trends that we don’t think of as being gendered that might have disproportionately made women less satisfied with their lives. It also could be women’s changed expectations–women expect a lot today and their expectations have moved faster than society has been able to deliver.”

Other areas of research into the economics of happiness are more certain. Higher public spending increases well-being, while income inequality reduces it. Perceived social mobility does seem to play a factor here, though–if people think they can get rich, they’re more willing to tolerate inequality.

Across most surveys, unemployment has one of the strongest correlations with unhappiness. Being around lots of other unemployed people seems to diminish this effect a little, but alongside poor health it’s one of the biggest contributions to unhappiness in a society. Inflation has a similar but weaker effect–though it’s stronger in those with right-wing beliefs.

Full-time workers tend to be happier than part-time workers, but there’s some complexity when it comes to overtime. Regular long hours tend to decrease well-being, but working overtime does give people greater job satisfaction. Meanwhile, being self-employed tends to make people happier, and so does a shorter commute. According to one German study, 22 minutes is the critical point where the length of your commute causes well-being to nosedive.

It’s tempting to trace the origins of happiness economics to Bhutan in 1972, when the Himalayan country’s dragon king announced a philosophy of Gross National Happiness over Gross National Product, inspiring the modern political happiness movement.

But the roots stretch back far further–from Aristotle, Confucius, and Plato to the work of English philosopher and social reformer Jeremy Bentham in the late 18th century, who declared “it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong.” You can see similar thought at work in Thomas Jefferson’s contributions to the U.S. Declaration of Independence, where he placed the “pursuit of happiness” on the same level as life and liberty.

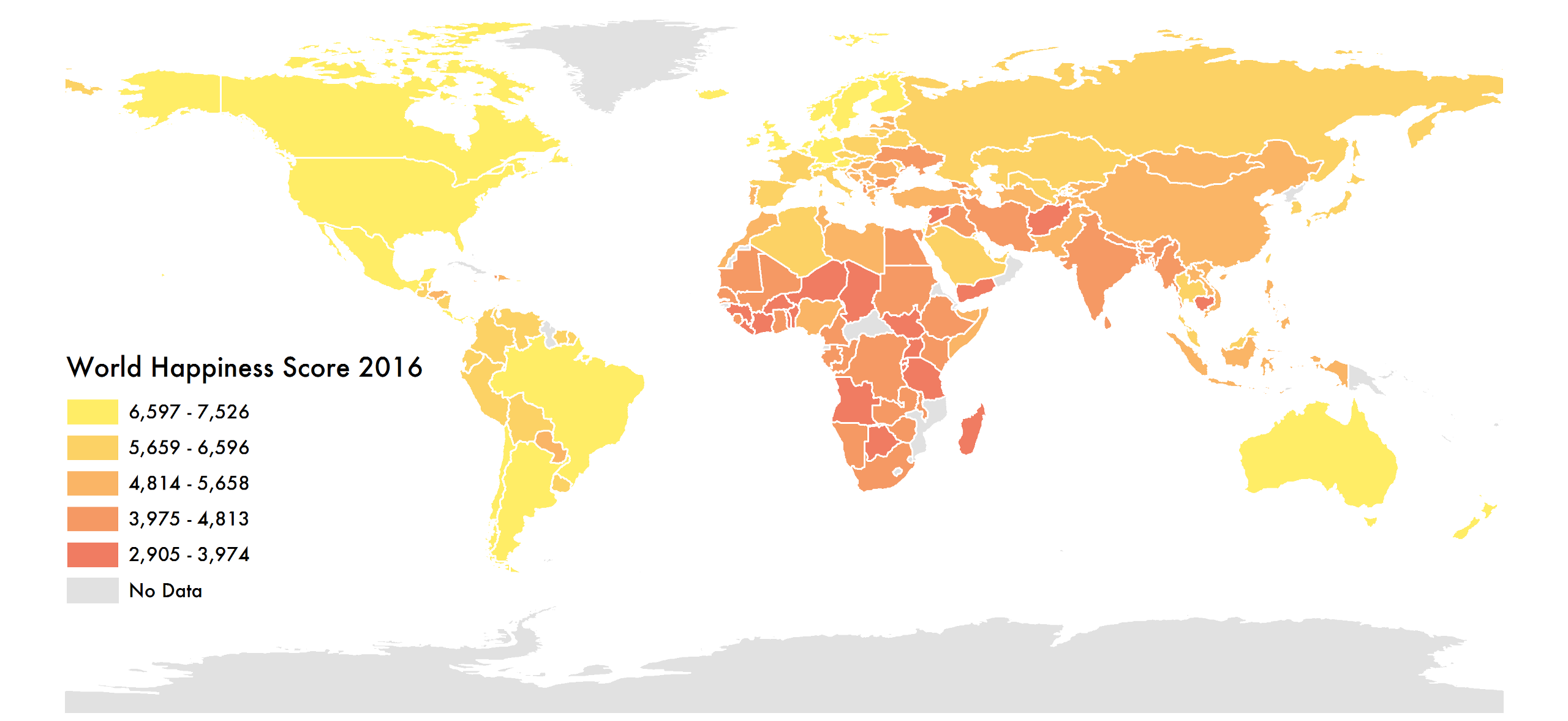

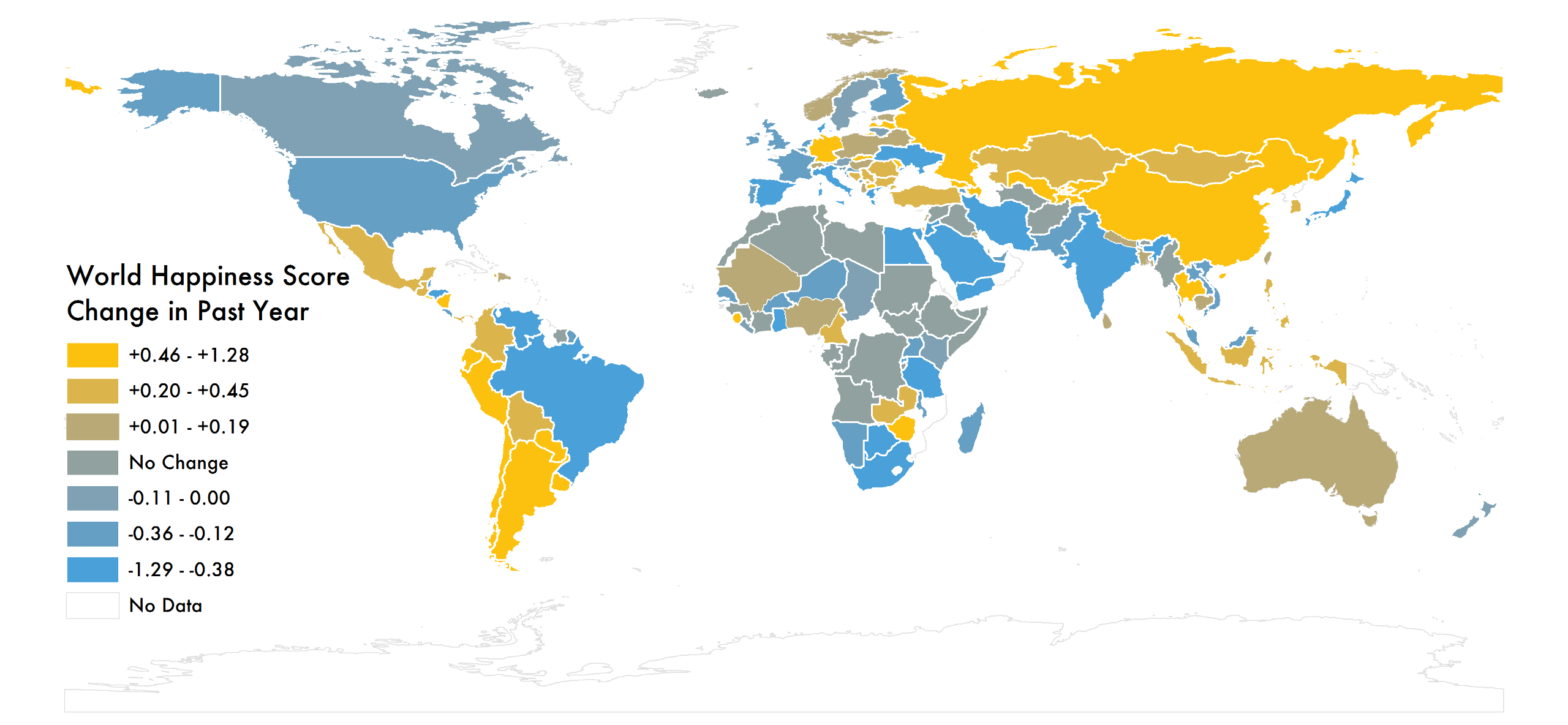

Today, many countries are looking beyond GDP and instead tracking the well-being and happiness of their citizens. In 2005, the International Institute of Management published a Gross National Well-being index, the first with global coverage. Since then, France, Thailand, Australia, South Korea, India, China, Canada, Singapore, Dubai, and the United Kingdom have all developed their own happiness statistics, alongside the United Nations’ own World Happiness Report.

In 2011, even North Korea joined the party with an International Happiness Index of its own. The hermit kingdom came in second, surprisingly, with the first-place prize going to China. Third, fourth, and fifth went to Cuba, Iran, and Venezuela, respectively, with the “U.S. empire” placing last. As you might have guessed, no information was provided on how the calculations were performed.

Some criticize the pursuit of happiness through statistics. At a happiness conference in Rome in 2013, researchers warned that data can be used to advance authoritarian aims–providing a justification for policies that reduce freedoms but purportedly increase happiness numbers. It would be nonsensical, for example, to argue that happiness has increased over the last centuries as the worldwide population of pirates has decreased as a case for greater spending on naval military assets. As such, governments should be wary of public policy that puts great emphasis on happiness statistics, as causation is often hard to establish.

Perhaps the best approach is to instead use happiness economics to inform our daily lives–warning us off poverty and unemployment, and pointing us toward spending as much time as we can with family and friends. Ultimately, research shows that we tend to look favorably on our past decisions, whatever the outcome.

“Gross National Happiness has come to mean so many things to so many people. But to me, it signifies simply, “‘Development with Values,'” said Bhutan’s King Jigme Dorji Wangchuck in 2015. “For my nation today, gross national happiness is the bridge between the fundamental values of kindness, equality, and humanity, and the necessary pursuit of economic growth.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Made of Money section, which covers the future of cash, finance, economics, and trade. Click the logo to read more.