As part of our Afrofuturism coverage, we’re featuring interviews with makers, artists, and thinkers from around the world. Afrofuturism is not just an aesthetic–it’s just as much a framework for activism and imagining new technologies. We’re interested in how the movement can make a practical difference in the lives of those from whom the thought culture draws.

Afro-Futurist space sculptor, performance artist, designer, writer, and educator D. Denenge Akpem is the founder of Denenge Design+Studio Verto; a lecturer at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in art history, theory, and criticism; and an instructor at Columbia College Chicago. Her courses include: “Ritual Art Performance in the African Diaspora,” “Black Arts Movement,” and “Survey of African Art.” In 2010 she first offered the course “Afro-Futurism: Pathways to Black Liberation” in conjunction with her artistic work in this field.

Florence Okoye: You’re someone who embodies different roles as artist, teacher, theorist, and activist. What would you say motivates you to take on such diverse roles and projects?

Denenge Akpem: Fundamentally, my motivation is about empowerment, of self, of communities, of my students, of the disenfranchised. I see Afro-Futurism as key to creating spaces for expression of the self and of the full range of one’s experience, but such spaces don’t often exist for black people. And additionally, even at our most “carefree,” there’s still internal self-policing at work that crops up from years–centuries–of disempowerment internalized. I believe in Afro-Futurism as a methodology of liberation that provides space in all its forms.

FO: How would you say your background and your journey influences your work?

DA: I was born and raised in Nigeria before moving officially to the U.S. for college. In a way, I’m very much the result of that heady post-colonial Nigeria, in all its good and bad. There was a sense of possibility even as we watched the government both promote and destroy hope with failed policies and crimes against its people.

My father is a Tiv pastor, writer, and professor from a part of Nigeria known for farming–yams, in particular, and fruit trees–with close connections to the land, and we continue to have a strong connection to this foundational origin, including artistically. My mother was the child of a Dutch immigrant to Chile and California and of my grandmotherm who traveled to California as a child with her family via wagon in the early 1900s. In the spirit of her grandmother, my mother had a renegade spirit, traveling to Nigeria as a very young woman to work as a nurse in an area with tremendously limited resources. Her creativity and support of indigenous art within the rehabilitation process in such a rural area had a tremendous effect not only on us, her children, but most essentially, the many people who benefited from this approach. For her, it was always about empowering individuals and communities–that led to Nigeria’s first-ever disability-rights law and the establishment of the National Spinal Cord Injury Association–and this has carried through for me in the work that I do as well.

So, I really credit my parents for encouraging our creative pursuits and for prioritizing our exposure to art across the country, from plant life to architecture to music, to religious traditions and textiles, to publications and festivals. I feel I really experienced so much of Nigeria and grew up with an incredible appreciation for the range of style and creative forms across ethnic groups and landscapes. They always collected and read children’s books to us–many from Nigerian publishers–and this helped to foster the imagination. Much of my work has tentacles directly back to the stories of my youth. Going to an international school also was instrumental in this.

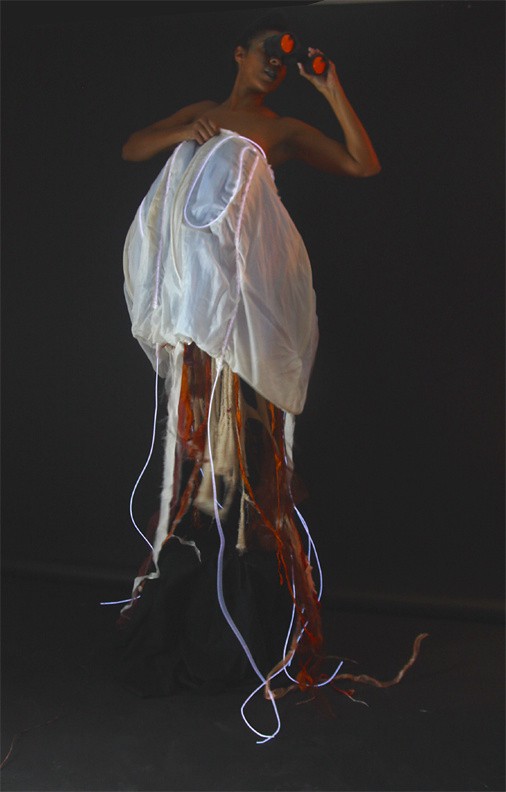

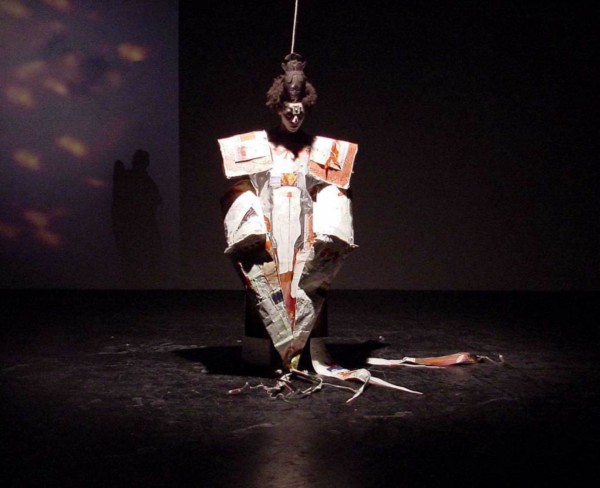

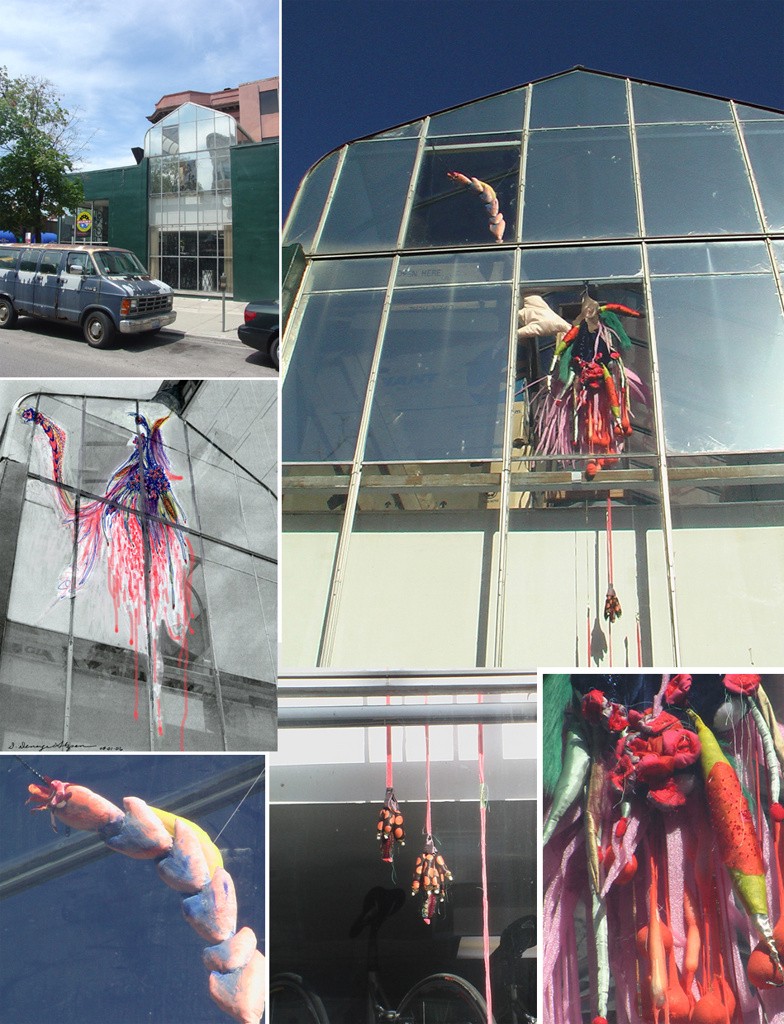

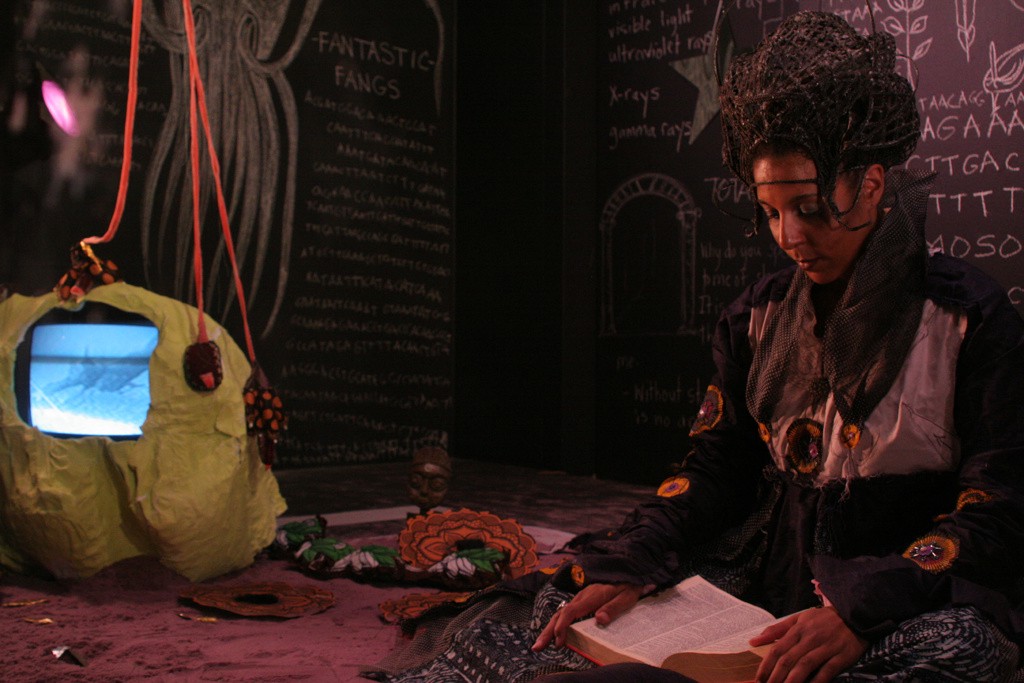

Additionally, I first really got into science fiction when my brother moved to Japan and left his collection of books with me. I was a broke grad student at the time and spent my free time reading every sci-fi book I could, including classics and obscure works. The connection to storytelling has always been strong, and for my Museum of Contemporary Art exhibition, I created a multimedia world based on investigations of fairy tales, the damsel-in-distress trope, and visions of black femininity titled “Rapunzel Revisited: An Afri-sci-fi Space Sea Siren Tale,” which was heralded as one of the top 10 exhibitions in Chicago that year and part of a new Afro-Futurism wave. My brother came up with the term “Afri-sci-fi,” and we give each other a lot of feedback. He is an incredibly talented designer–primarily focused on digital storytelling–and our continued collaboration is one of the great joys of my life.

FO: That idea of empowering through art, making a space for oneself through creation, how does that inform your work as a teacher?

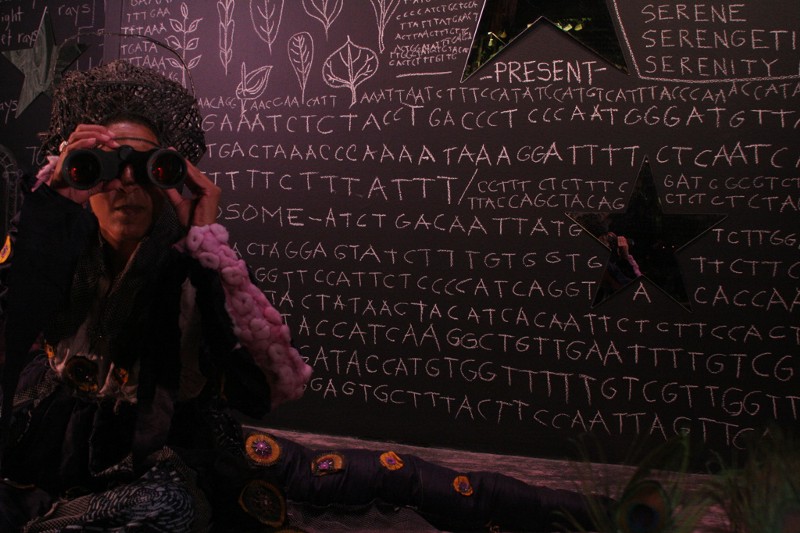

DA: The Afro-Futurism classes push students to go beyond external and internal challenges and boundaries. I utilize a cross-disciplinary approach to help my students develop key foundational visual art and critical thinking skills. The syllabus includes investigations into “sonic architecture” (inspired by Julian Jonker, and the work of Paul Miller DJ Spooky and Kodwo Eshun) which students apply in the creation of their own sound works. [These are] based on Octavia Butler’s Patternist and Xenogenesis series, and what I have termed “vessels of liberation,” including body as vessel from the music of Sun Ra to Nigerian masquerade traditions. Since this is an evolving and dynamic subject, I see students as part of the Afro-Futurism community and as contributors. Afro-Futurism is a living and breathing world. So I present a wide range of perspectives, approaches, and definitions which ultimately allows them to determine what Afro-Futurism means to them and to leave space for viewing works of art and practitioners who can be linked to Afro-Futurism without defining them (solely) within that category.

I often think of artists as trained superconductors or live copper wires. Wole Soyinka talks about the fourth stage, the realm of Ogun the creator and destroyer who creates a path between orishas and humanity. To me, artists are in many ways the embodiment of Ogun energy– alchemists. I believe in training young artists–especially those involved in ritual work and black-focused artwork–to move through the creative process, through that realm, but to come through the other side. It’s a cyclical process, a growing and purging, and that process takes training, especially for superconductors. If you get stuck in that chthonic realm, that’s when there’s trouble.

Parallel to that, I believe in learning to love–or at least, appreciate–reading and writing contracts; the final pages of my syllabi include a page for a signature (like a written contract) to bring a level of professionalism and to signify that this is a contract we share together, a commitment to the work. Artists need to be aware of the importance of owning their projects, their processes. Particularly for black women in the U.S. where systemically there is an expectation of free labor and shame if it is not given, or where labor is expected with little compensation, sometimes not even a “thank you.” So as an artist myself instructing artists and future cultural producers, I want students to understand systemic issues, to value their own work and to value–and compensate–others’ work when they are in positions to do so, whether as filmmakers, curators, administrators, and so on. Part of my practice inspired by the visionary world of Afro-Futurism is about being real, honest, and straight-up about the realities that I face and that others face; moving past fear of “punishment” or being ostracized by the status quo to speak truth.

FO: What sort of materials do you work with? Did you always work that way? How have you found your style developing? What, in your opinion, has influenced it?

DA: Both my parents encouraged creativity through making things, which has inspired the way I focus on materials themselves in a utilitarian manner. I was creating functional, designed objects from a young age and coming up with marketing ideas for them. I’m fascinated by materiality, by couture, old-world ways of production. You see that in my site-specific design, interior projects, and sculpture, which are very much focused on materials and on transmitting experiences through a range of media and on creating intentional spaces as a supportive foundation for transformation. “Sculpting Space,” for example, a site-specific residential commission, was an exercise in synaesthetic sculpture based on a soundwave pattern, a phrase of meaning spoken by the client, translated into light sculpture, set to mirror the horizon line of Lake Michigan. Each aspect of the sculpture is specific to the client; it grew from and continues to be a symbol of the individual. I connect this very much with studies of feng shui and space healing, and it is an early manifestation of my study of space as a transformative medium within the Afro-Futurist framework.

FO: Technology has certainly enabled transmedia narrative. As someone who does so much work with the body in your ritual performance, what’s your experience on transmitting physicality and presence into different media?

DA: Well, my background and training includes an M.F.A. in performance art from Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC), which is where I finally started bringing together all of the threads of my practice in theatre, sculpture, sound, costume, and digital technologies. In terms of transmitting physicality and presence into different media, I feel that I insert myself in multiple forms; as a voice with singing and soundscapes, as a costumed figure part of the sculptural space itself in video projections, and even in the creation of space for the absence of form–the missing body.

I recently had the pleasure of contributing my voice to the animated film The Golden Chain. I play Yetunde, a scientist in a futuristic Yoruba tale. I was trained as a vocalist and often utilize this in my work, but this was a whole new experience of being only a voice, disembodied, which was great! I enjoyed being in the recording studio again and contributing to the work of artists whom I greatly admire. The film just screened at The Flaherty in New York in a series curated by Lana Lin and Cauleen Smith, and will be traveling nationally and internationally this year. Original excerpts were screened as part of the “Black Radical Imagination” series.

FO: That reminds me of something Lupita Nyong’o said about her role in Star Wars: The Force Awakens–that in some ways it was quite liberating working on a role where her body was not the center of her performance. I think there’s something quite challenging in the idea of technologically-enabled disembodiment being liberating for the black woman.

DA: It ties into questions about how are we defining what it means to be a black woman, both now and in the future. And I think also it provides liberatory, alternate ways of expression outside of the framework of how the world–and often how we–see ourselves.

FO: Exactly! Is it “black” because I am explicitly talking about blackness? Or explicitly drawing on my experience as a black woman? Or is what I do “black” because, well, I am black?

DA: This is a fascinating question connecting to studies of black aesthetics. I recall a quote from a conversation about the role and expression of blackness within the work of black composers, to which there was a wide range of responses. Composer Olly Wilson spoke about how his work is “black” because he is black; whether you see what you think is “black” in the work or not makes no difference.

And that question of how we express the universe of what it means to be black is partly what drew me to Afro-Futurism. My interest was rooted, in part, in the Black Arts Movement–the artistic, cultural, and literary arm of the Black Power Movement–begun by Amiri Baraka and others in the wake of Malcolm X’s assassination. I would say that my approach as an Afro-Futurist artist is rooted in foundational concepts of B.A.M. as both a political and social expression of empowerment for black people. At the same time, many of the artists of that time who I look to for inspiration where considered “out there” and sometimes were even ostracized for not conforming to a certain kind of “black” representation or gender expression.

FO: What do you think about the term “Afrofuturism”? It’s interesting it was coined by a white cultural critic, but it seems to have stuck. Do we need a new label or does even arguing about labels limit our ways of thinking?

DA: I understand the issues that people have expressed with the term, and even with the term “futurism” and its links to fascism. For me, Afro-Futurism is where technology meets the vision. It is the seed of the last truffula tree and the singing of whales that sound like the humming of Saturn’s rings. It’s about loving our history, our present, and our future within a continuum.

I consciously choose to call it Afro-Futurism, rooting it first and foremost in the “afro.” First, with the connection to B.A.M. and that era in terms of claiming new names for ourselves, Malcolm X and others used the term “Afro-American,” and so for me, I use that with the hyphen to link to that time period in the development of Afro-American identity. Additionally, and probably most importantly, I look to Mark Rockeymoore’s essay “What Is Afrofuturism?” where he talks about the afro as a spiral entity that can’t be defined, can’t be contained. That, for me, is Afro-Futurism. To be honest, though, I avoid contention! We can have multiple terms for this area of study and art. That’s the beauty and possibility of this subject! Afro-Futurism is the truest expression of infinite liberation.

FO: Right, so why contain it with the kind of arguments you find so often in mainstream liberal arts? I get what you mean: If Afro-Futurism is finding a new way of doing things, then maybe we even have to critique the way we debate about this kind of stuff, lest we fall into the same old traps.

DA: I also think a lot of this is due to the way things have shifted. Now Afro-Futurism is seen more as a movement. When I started out, the term was definitely not mainstream, but now it’s everywhere.

FO: I really like your quote: “Afro-Futurism is an exploration and methodology of liberation, simultaneously both a location and a journey.” It’s like the Afro-Futurist uncertainty principle! How do you reconcile that contradiction through your work?

DA: Well, this comes from my study of African ritual performance and of “process versus product” within the Black Arts Movement. I am interested in the dynamic, and moving away from the static. Really considering the principle of AshÄ”, the catalytic life force as art historian Rowland Abiodun has described it, that exists within us but also within works of art and within the interaction between us and the work of art.

You’ll find that in many West African dramatic approaches, improvisation is the marker of virtuosity, an active and activating process. The value is within process rather than end-product; focusing on this is a different way of operating and being. That sense of honoring artisanal alchemy, respecting indigenous sciences, is at the heart of Afro-Futurism. It’s not necessarily about final answers, but about the making, the process.

FO: As a lecturer, do you find that many younger people know about Afro-Futurism? I’m always interested in how few people my age and younger know about Afro-Futurism, per se, but they do know about and like Janelle Monae. Do you find there’s an awareness amongst younger students about Afro-Futurism?

DA: I think there is an awareness for sure. They know about the work of some of the more popular artists, and they’re drawn to the topic by a common interest in the renegade. Afropunk has done a lot to popularize a certain renegade style. It’s another wave in time, another iteration, but perhaps a freer one or a more accepted one that connects to a history of black renegades, experimenters, and adventurers. I find so-called millennials fascinating, as they have such different and often progressive ideas about themselves and society but can be weirdly old-fashioned, like they’ve stepped out of 1865!

More seriously, though, I find there’s a desperation amongst students for this content. Many of them locate themselves within the margins (I look to bell hooks’s description of the margins as a foundational premise), the geeks (a point of pride and positive location as one can be a “tech geek,” an “art history geek,” etc.), those outside of “respectability” or mainstream, and those who want to push their practice beyond narrow popular restrictions. They are, like me, inspired by trailblazers, by renegades who operate outside of society and create alternative worlds, alternative identities. They are intrigued by the term and want to know more. My focus is the creation of space to nurture this impulse.

FO: Finally, what are you looking to work on in 2016?

DA: Splendidly sexy stuff! That’s my goal this year–to continue working with Afro-Futurism as a deep liberation, being playful without divorcing Afro-Futurism from its political underpinnings.

I am designing costumes for a new Pixel Fable multimedia story with my brother, designer Senongo Akpem. I’m also collaborating with a team of designers for Honey Pot Performance’s new work Ma(s)king Her, a dance theatre work of speculative fiction, debuting at the Pritzker Pavilion in Millennium Park this April 2016. I’m in charge of some set design and headdresses, bringing an Afro-Futurist, fantastical sensibility to the story, which takes place across multiple times and spaces.

My site-specific sculpture practice is also a big focus, so I’ll be engaging in a range of new projects in the coming year as well. I continue to share my own and others’ work at The Afro.Futurists blog and am developing new art history and performance-based courses to bridge the trajectories of my work, in addition to speaking on the subject nationally and internationally. I look forward to collaborations with Afrofutures UK and with the AfroFuturist Affair, the Spacesuits, and Octavia E. Butler Legacy Network. In fact, I’m excited to share that The Golden Chain will be shown in October as part of “Let It Be Known,” curated by Erin Christovale of “Black Radical Imagination” for Clockshop’s “Radio Imagination,” a year-long series celebrating the life and work of Octavia Butler in collaboration with the Huntington Library where the Octavia E. Butler papers are held.

My focus also is moving more toward Afro-Futurism in Africa, to connect with practitioners and manifestations across the continent.

I am inspired by the recent sharing of Octavia Butler’s notebook where we see how she literally wrote her future into existence. Manifest! Ashe!

D. Denenge Akpem’s work is available at www.denenge.net. Visit theafrofuturist.tumblr.com for featured events and happenings, art, design, and sound.

Further reading

This article forms part of How We Get To Next’s January 2016 conversations about Afrofuturism, in collaboration with AfroFutures_UK. (Image credit: Naomi Mabita.)