In his book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell writes that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to become a world-class expert in any field. As long as you put in the hours, he argues, eventually you’ll hit the magic mark.

Too bad the researchers whose work informed the basis of Gladwell’s rule say he got it wrong. Instead, they claim the time it takes to become an expert actually varies from person to person and field to field. Also, apparently expertise involves engaging in “deliberate practice,” which means “constantly pushing yourself beyond your comfort zone, following training activities designed by an expert to develop specific abilities, and using feedback to identify weaknesses and work on them.”

Of course, even with these added parameters, you’re still looking at thousands of hours of labor to achieve anything like the proficiency of the world’s best thinkers, athletes, and artists. Disheartened yet? We’re betting on it–but what if there was a way to speed up the process?

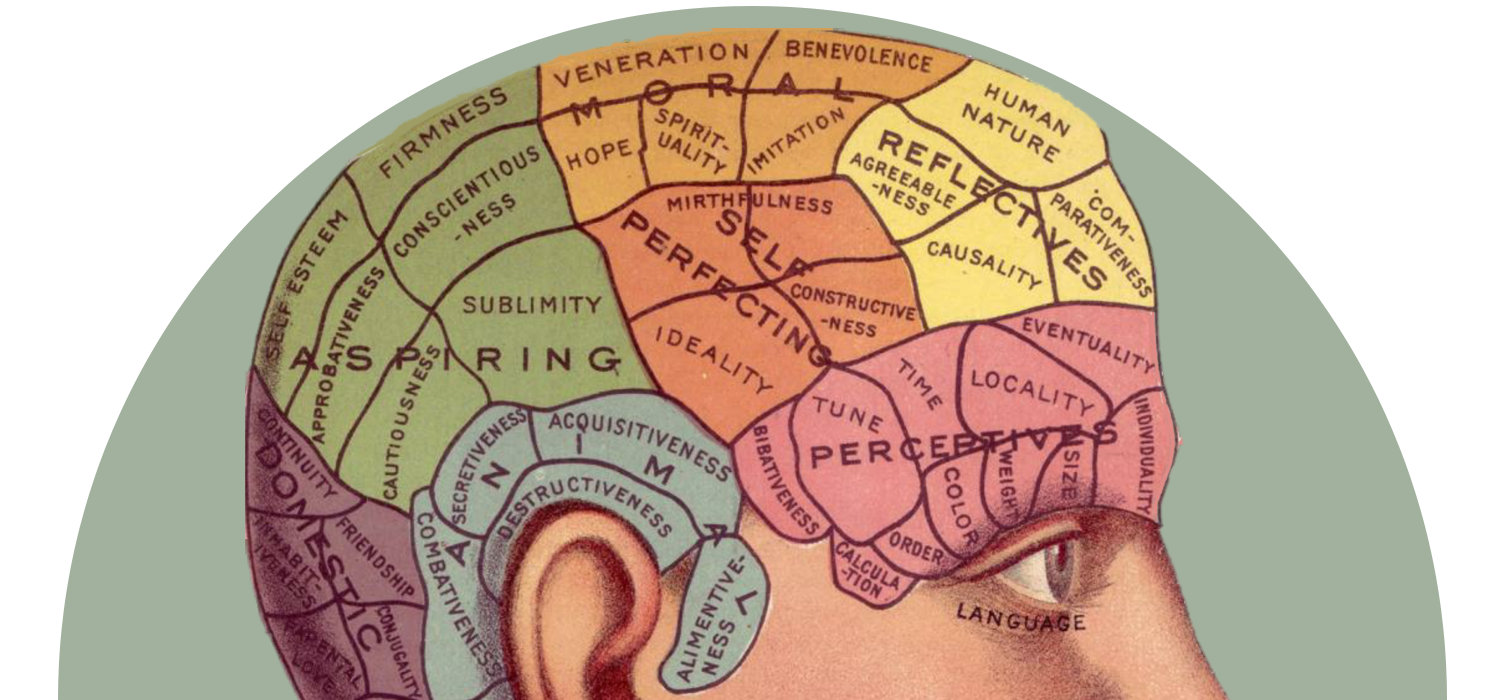

It’s been a long-held dream to shortcut learning and master mastery. But no matter your end game–whether it’s going toe to toe with the pros or simply holding your own against a friend–if you weren’t born a prodigy, time has always been a primary requirement.

These days, it’s something we’re almost all short on. But basic economics indicates that where there’s demand, they’ll soon be supply. Hence the launch of a number of brain hacks that claim to help us increase the pace of our knowledge intake.

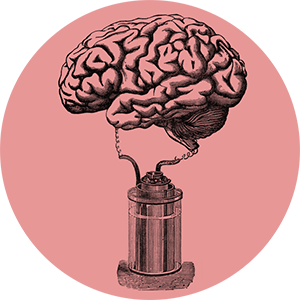

For the past few years, there’s been a lot of talk about shooting electricity into our brains to increase intellectual function–a technique known as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Developed to help patients with brain injuries or severe psychiatric conditions, tDCS delivers a constant, low-level current to the brain via electrodes placed on the scalp. Some trials appear to indicate that the process could improve working memory, language skills, and learning speed, though the ability of tDCS to enhance the cognitive functions of healthy adults is highly disputed within the scientific community.

The results of each tDCS session are highly influenced by what activities you do while the current is active, its amplitude, duration, and the placement of the electrodes. In 2015, a meta-analysis of 59 studies also found no “reliable effect of tDCS on executive function, language, [or] memory.” Meanwhile, the results of recent research carried out on a cadaver’s skull showed that the skin may direct up to 90 percent of the current used during a typical tDCS session away from the brain. This led neuroscientist Vincent Walsh of University College London to comment that the tDCS field is “a sea of bullshit and bad science–and I say that as someone who has contributed some of the papers that have put gas in the tDCS tank,” he said.

Other researchers have found that tDCS could actually reduce your IQ. Then in 2014, Roi Cohen Kadosh, a professor of cognitive neuroscience at the University of Oxford, discovered that just as brain stimulation might improve anxious people’s performance at some maths tasks, it can likewise impair the brain function of normal, high-performing individuals without anxiety.

Nevertheless, Dr. Jenny Thomson, a researcher at the University of Sheffield who has used tDCS in her clinical work on literacy and learning disabilities, says there is considerable research showing that tDCS can have an effect on cognition. This is especially evident in terms of enhancement in the motor or sensory parts of the brain, particularly when there is an injury or other problem within that area. But, in some respects, “It’s still quite a blunt tool,” she adds. “The sensors are relatively large, and we don’t know exactly how deep or wide the area is over which the stimulation has an impact. Also, most cognition happens because of activity in various interconnected parts of the brain, so this may be why we are seeing smaller effects on cognition than ‘simpler’ parts of the brain like the motor cortex.”

Despite the unknowns, the ease and cheapness of carrying out tDCS research has birthed a robust community of DIY biohackers who believe electrical brain stimulation will improve their cognitive functions and alleviate their mental health problems. While commercial tDCS products such as Foc.us V2 Stimulator and Halo Sport claim to help you “learn new skills faster” and “unlock your potential,” it’s easy enough to perform tDCS with two saline soaked sponges, two electrodes, and a 9-volt battery. Current flows between the positive anode electrode, increasing the likelihood that certain neurons will fire, and the negative cathode electrode, which inhibits them from doing so.

Alarmed by the increase in DIY tDCS, 39 scientists–many who study the effects of neurostimulation–recently signed a letter that was published online in the journal Annals of Neurology, urging people to approach tDCS with caution. “Home users of tDCS devices need to be aware that we do not really understand how stimulation brings about the intended results or how surrounding brain regions are affected,” the authors warned, “but we do know that the brain changes they bring about may be long-lasting, for better or worse.” Dr. Anders Sandberg, a research fellow from the Future of Humanity Institute at the University of Oxford, agrees. Even if DIY brain hackers are suitably cautious, he tells me, until more trials are done we won’t “fully know the long-term risks.”

But there’s still those like Andrew Vladimirov, a London-based biohacker and transhumanist, who regularly uses neurostimulation techniques like tDCS, as well as more advanced and potentially more promising forms such as transcranial magnetic stimulation, pulsed ultrasound, and laser light. In fact, he’s turned part of his home into a laboratory dedicated to hacking his brain. Vladimirov believes neurostimulation is useful “when you have to push your limits” and that tDCS can be used to enhance “specific tasks,” citing recent tDCS trials by the U.S. military that claimed to boost the performance of air crews and drone operators.

When I ask him about the warnings, he doesn’t seem particularly phased. “I regularly face critics who say, “‘We don’t know that much about our brain, our mind, what the hell the consciousness is.’ Well, fine,” he says. “We knew even less a hundred years ago, 200 years ago, 500 years ago. The only way of moving forward is to lift your backside from your armchair and actually try something.”

All disputes aside, one of the keys to learning is focus. If you struggle to concentrate on what you’re supposed to be learning (and who doesn’t when a video of a skateboarding dachshund is only a click away), you are never going to improve. Attention is where many of us come undone. But if you’ve seen Limitless or Lucy, you’re already familiar with another rapidly commercializing form of supposed cognitive enhancement: nootropics.

Although the superhuman abilities Bradley Cooper gains from the imaginary NZT-48 pill are nothing but a screenwriter’s dream, companies like Nootrobox, Nootrobrain, truBrain, and Nootro are attempting to capitalize on growing public interest in “smart pills.” That their products often come with disclaimers like “intended for use in neuroscience research only” demonstrate that the supplements currently exist in something of a regulatory gray area. Furthermore, despite the grand claims that these pills’ super-secret recipes will improve your cognitive performance, other than a caffeine boost it’s not clear what effect–if any–they have on your brain.

As with DIY tDCS, there’s a growing community of people using drugs–like the wakefulness agent Modafinil and central nervous stimulator Piracetam–off-label in an attempt to improve their focus and memory. Small but significant numbers of students, gamers, high-flying professionals, and Silicon Valley whizz kids experiment with smart pills to pass exams or maintain an edge over their colleagues and competitors. Some even whip up their own powder-based concoctions in the kitchen, Walter White-style, and share their favorite “stacks” online.

But just because a drug has been shown to help people suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), that doesn’t mean the benefits automatically transfer to healthy individuals. The effects of each drug or stack vary from person to person, and the long-term effects from regular nootropic use are little understood–especially on developing brains, a process that happens in humans until we’re around 25.

Even so, a recent meta-analysis carried out by researchers from the University of Oxford and Harvard Medical School appeared to show some promise for nootropics, concluding that Modafinil is a cognitive enhancer (though the review methodology was criticized by the chairman of the British Medical Association Occupational Medicine Committee). Anecdotal evidence also indicates that some people find nootropics keep them alert and focused for long periods–though prolonged, frequent doses of certain drugs may induce a bout of extreme burnout, which seems only logical. If you drive your brain at full-throttle for days on end, sooner or later you’re bound to crash.

If nootropics and tDCS seem a little extreme for your taste, don’t worry–there may be other, more benign alternatives. In his third best-selling book, The 4-Hour Chef, Tim Ferriss promises to teach anyone how to master the skill of accelerated learning with a technique he’s coined “meta-learning.” Essentially, it’s learning how to learn.

At the heart of his system is a four-step process: deconstruct, selection, sequencing, and stakes. If you want to learn how to play tennis, for example, first break the sport down into its “minimum learnable units.” Next, use the 80/20 rule to select the units that make up the 20 percent of subject matter you’ll need to know to become 80 percent competent. Then decide which order to learn them in, and introduce stakes to make sure you follow the program–that is to say, enter a tennis tournament. The point is to change your learning behavior so that you reach proficiency in less time. Of course, there’s products to assist you.

The Pavlok wristband, for instance, delivers a small electric shock to your wrist every time you indulge in bad habits (it can also be set to beep), thereby conditioning you to knock them out–or so the manufacturer claims. The product’s name, at the very least, is based on Ivan Pavlov’s theory of classical conditioning, which primarily investigated the behavior of dogs around certain stimuli before food was presented to them (you know, the bell, the salivating, all that).

At home, you can set the Pavlok wristband to monitor all sorts of behaviors, from oversleeping to overeating, with IFTTT rules. A free web-based service, IFTTT allows its users to create simple, conditional, If This Then That statements that can trigger a tie between web services or apps. Usually, it’s something like, “If I get tagged in a picture on Facebook, add it to my cloud-based photo library.” In the case of the wristband, imagine: “Beep [my] Pavlok loudly when [I] get too close to [my] favorite fast food restaurant” as a reminder to turn around. This actually comes closest to original Pavlovian theory, which focuses on preceding conditions to alter behavioral reactions. But it works both ways. For learning purposes, having the Chrome extension that links your browser and wristband set to shock you each time you visit a site from your blacklist, or go over your tab limit, might be a better bet.

Another thing you can do to accelerate learning is start listening–not to teachers but to music. Focus@will is a streaming service that claims it can increase your attention span by up to 400 percent using “neuroscience-based music.” Touting a variation on the Mozart effect–the belief that listening to Mozart’s music can improve your ability to carry out certain tasks and may even make you smarter–the “scientifically tested technology” is marketed to help you avoid “two undesirable states: distraction and habituation.” Apparently it works by “subtly soothing the part of your brain, the limbic system, that is always on the lookout for danger, food, sex or shiny things.”

The subscription-based playlist company even has research papers to back up these claims. And yet, while there’s evidence that non-vocal music can increase your productivity when carrying out tasks that require focus but little high-level cognition, this feels like a liberal use of the term “neuroscience” overloaded with commercial promise.

Regardless of its scientific merits, soothing music generally seems preferable to the sound of wall-thumping headboards or coughing colleagues. My own playlist for work consists mainly of videogame soundtracks: They’re effectively designed to keep you immersed in games that test your cognitive skills, and they seem to do a great job of blocking out the world when I need to write. But could games actually improve your IQ?

There’s a whole host of online brain-training games that say yes. Ones like BrainHQ, CogniFit, and Lumosity are marketed to offer cognitive benefits in exchange for a subscription fee and few minutes of your time each week. In 2014, however, nearly 70 researchers wrote an open letter railing against them: “To date,” they wrote, “there is little evidence that playing brain games improves underlying broad cognitive abilities, or that it enables one to better navigate a complex realm of everyday life”–a claim that a second group of 133 scientists and practitioners refuted in another open letter.

Although this war of words is ongoing, a subsequent comprehensive review of relevant literature discovered that the only thing brain-training games might improve is your skill at playing them. In a further blow to the industry, researchers at Florida State University found that undergraduates who played Portal 2 for eight hours performed better on cognitive tests than undergraduates who played Lumosity for the same duration of time. In January of 2016, Lumos Labs agreed to pay the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) $2 million to settle false marketing allegations against its Lumosity brain-training game (the FTC said Lumosity “simply did not have the science to back up its ads.”)

Looking into the future, might we one day see the kind of instant-knowledge brain uploads featured in The Matrix? “I think we are getting better and better at micro and nanotechnology, and this allows implants that are safer and more convenient,” says Sandberg. “Eventually they may be good enough that healthy people will want them. One can also enhance stimulation methods by better scanning so that we can find the right spots, and maybe by using nanoencapsulated enhancers that can be made to release in them.”

But before I get carried away with the prospect of becoming a kung fu master on the spot, he adds: “Downloading knowledge is hard–a drug or stimulator doesn’t have many bits of information, and worse, each brain represents knowledge in a different distributed way. So we need to map brains in great detail and translate from one representation to another. That will take a while.”

Still, I can’t help but wonder whether the gains that instant knowledge might offer society as a whole could come at the expense of the joy we all feel in learning something new–especially when it’s a skill that’s hard to master. There’s something special about watching someone exercise a unique and well-honed talent, whether it’s Roger Federer reaching for and making an impossible shot, or Jimi Hendrix doing mind-blowing things on a guitar. What happens when mastery is no longer unique but ubiquitous?

Then again, perhaps some forms of brain stimulation will eventually help to level the learning playing field. Those hours and hours of learning often come with a price tag after all–one many people on low-incomes can’t afford. Perhaps if each one of us has professional-level base skills we’ll even see fascinating new forms of art arise, or scientific breakthroughs impossible to imagine right now.

But for now anyway, we’ll still need to put in concerted effort and time to become truly accomplished at something. Our best bet for speeding up the process? Maybe trying one of the safer brain hacks–or perhaps just lots of sleep, regular exercise, and a healthy diet. Boring, sure. But if we know one thing, it’s that it’s hard to beat a tried and tested method.

This post is part of How We Get To Next’s How We Learn month, looking at the ways we educate around the world throughout December 2016. If you liked this story, please click on the heart below to recommend it to your friends.